The Strangely Successful History of People Mailing Themselves in Boxes

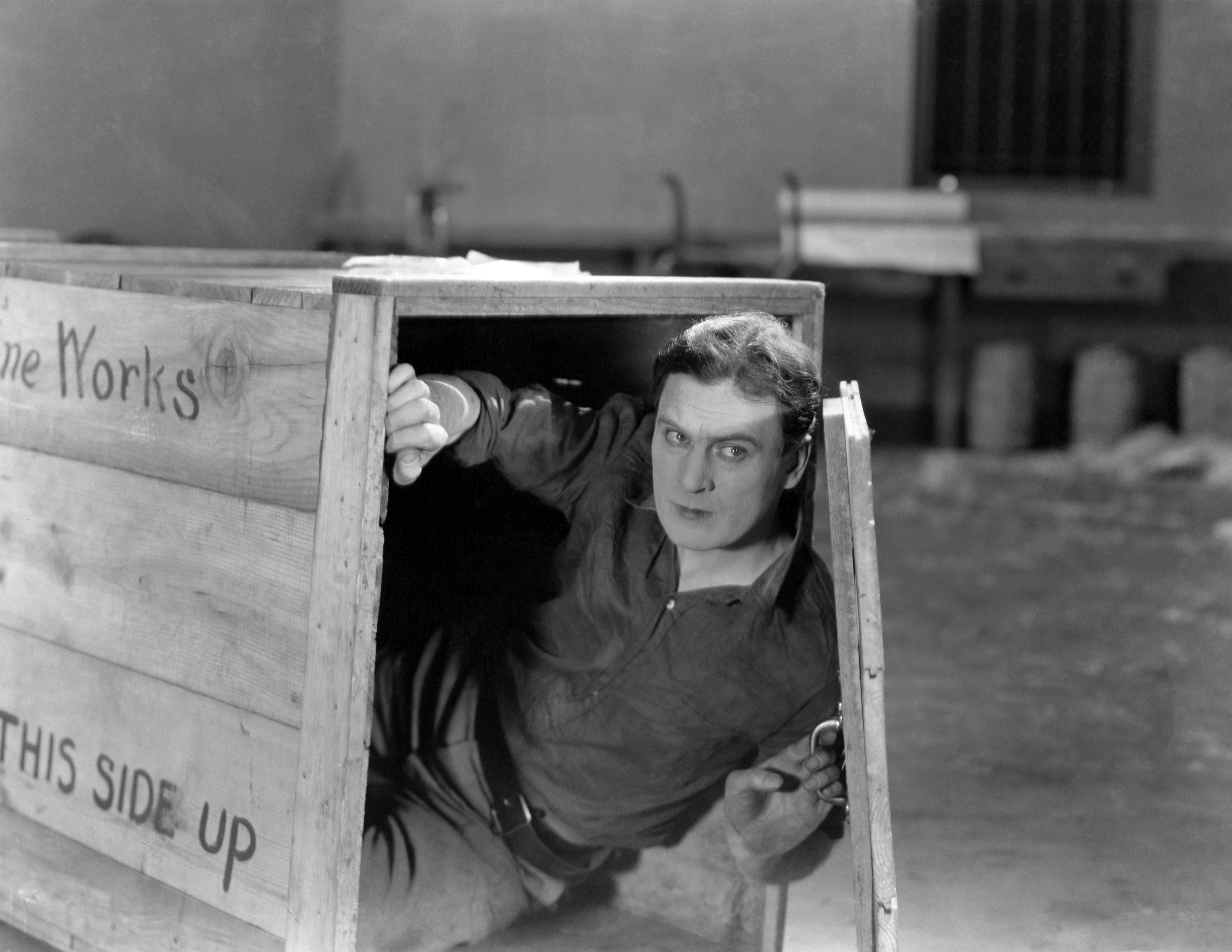

(Photo: Everett Collection/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: Everett Collection/shutterstock.com)

The communication from FedEx’s media relations team was brief. “Dan,” a FedEx employee identified over email only as “Media Relations” wrote, “The shipment of humans is prohibited in our network as a matter of policy.”

But behind that banal corporate phrasing lies a rich history, a subset of the stowaway phenomenon—the story of people attempting to mail themselves in boxes.

Like stowaways on ships, trains, and planes, people have attempted (and sometimes succeeded!) in mailing themselves as recently as just a few years ago. It’s not easy, nor legal, nor permitted by any major shipping company, but that hasn’t stopped a very special group of people from trying.

Whether to escape slavery or merely the cost of a plane ticket, people have been trying for over a century and a half to package themselves like so many rolls of toilet paper from Amazon.

Searching a ship for stowaways, c.1850. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The specific concept of a stowaway probably dates back to the early 1800s. Freighthopping, or leaping onto a train, became especially common after the Civil War, and stowaways on ships reached their peak in the early decades of the 1900s. It’s a dangerous thing to do; secreting oneself in the bowels and containers of a ship carries with it the risk of suffocation, starvation, and thirst. A stowaway’s legal position is rarely secure, and if the stowaway is discovered, he or she is unlikely to find much sympathy from a ship’s crew.

As travel technology changed, the romantic notion of a stowaway took a hit. Stowaways on planes are more rare due to the near-suicidal level of danger in the strategy. Wikipedia maintains a lengthy, though sometimes uncorroborated, list of attempts to stow away in the wheel well of an airplane, an empty space just large enough for a human. This is a bonkers thing to try, as temperatures can reach -81 degrees F, the pressure from the elevation collapses lungs, and there’s not nearly enough oxygen to survive at even relatively low cruising levels. The only modern surviving airplane stowaways, like 21-year-old Indonesian man Mario Steven Ambarita, who survived a flight from Sumatra to Jakarta earlier this year, have tended to try for short flights at low altitudes.

But mailing oneself in a box, that’s something different. Shipping companies like FedEx and the United States Postal Service (USPS) ship packages in temperature-controlled, pressurized cargo holds. A box itself provides some level of privacy and security, though it also minimizes one’s ability to move. And staying inside a box allows one to remain, sort of, in plain sight: once you’re past the initial line of security, you can stay put and await delivery.

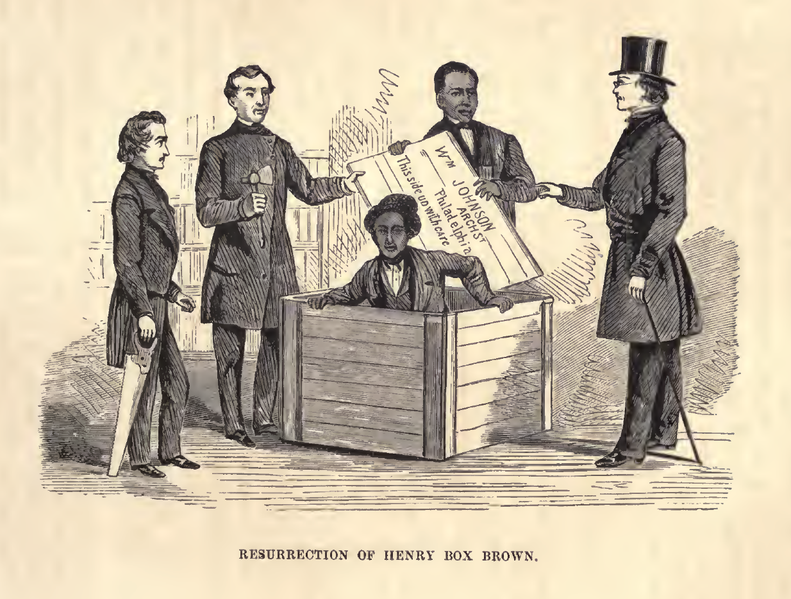

Illustration of Henry Box Brown’s ‘resurrection’ in Philadelphia, from the 1872 book “The Underground Railroad” by Willliam Still. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Illustration of Henry Box Brown’s ‘resurrection’ in Philadelphia, from the 1872 book “The Underground Railroad” by Willliam Still. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Perhaps the most famous self-mailer is Henry “Box” Brown, an escaped Virginia slave who mailed himself to Pennsylvania, a free state, in 1849. Brown severely burned his hand to get out of work one day, then, in collusion with abolitionists in Philadelphia, had himself packaged into a box equipped with a bottle of water, a few biscuits, and a rough blanket, and shipped via the Adams Express Company, now an investment firm that in the 19th century was a shipping and freighting company known for its privacy. The shipping cost Brown $86, just over $2,500 in today’s dollars, and took an extremely uncomfortable 27 hours. But he was delivered successfully, and became a well-known abolitionist speaker and entertainer later in life. (Apparently Frederick Douglass was annoyed with Brown for revealing his method of escape, thus preventing other slaves from doing the same.)

Reg Spiers, who posted himself in a box from England to Australia. (Photo: Courtesy Marcus McSorley/ Roaring Forties Press)

Much later, in 1964, Reg Spiers, a near-Olympic-level Australian javelin thrower, found himself stranded in England after failing to qualify for the English Olympic team. Spiers told the BBC earlier this year that his wallet was stolen, leaving him penniless, and that his best option for getting home was to mail himself in a large crate, cash on delivery, and figure out payment when he got home to Australia. A friend, John McSorley, built Spiers a box, 5 feet by 3 feet by 2.5 feet, equipped with some straps so Spiers could hold himself steady as he was moved.

The box was loaded with Spiers himself, a pillow, a blanket, some cans of food, a bottle of water, and an empty bottle as a makeshift bathroom, and sent to Australia. Amazingly, after delays in London and an especially brutal layover in steamy Mumbai, Spiers survived the three-day trip home. Back in the Perth airport, Spiers says he let himself out of the box and cut a hole in the airport’s wall. After stealing a beer from the cargo area and dressing in his own suit, he simply walked out of the hole he’d cut and hitchhiked home.

The box being inspected at Perth International Airport. (Photo: Courtesy Marcus McSorley/ Roaring Forties Press)

The box being inspected at Perth International Airport. (Photo: Courtesy Marcus McSorley/ Roaring Forties Press)

Little did he know that McSorley, having not heard from Spiers for days, was getting worried, and alerted the press. So within a week he found himself hounded by reporters wanting to know about his amazing journey. The attention did have one nice effect, though: the airline forgave his debt. (Another outcome was that McSorely co-authored a book called, appropriately, Out of the Box, about the whole affair.)

A replica of the box Reg Spiers travelled in. (Photo: Courtesy Marcus McSorley/ Roaring Forties Press)

I contacted both FedEx and the USPS to find out about shipping myself. Both prohibit it, though it’s worth noting that the USPS employees I talked to have a sense of humor about this kind of thing and gleefully chatted with me about the weird stuff you’re allowed to ship.

Legally, you are allowed to ship only very specific types of live animals. Those include day-old birds, certain adult birds (chickens, for example), bees, a selection of cold-blooded animals including baby alligators and chameleons, and, bizarrely enough, some scorpions. “Yeah, bees, crickets … I used to work in the processing plants when those things would come through. They must be packaged very specifically to protect the insects and the postal workers,” says Sue Brennan, senior public relations specialist at the USPS.

The rules for mailing baby alligators are as follows: The alligator must be under 20 inches in length, it must not require any food or water during its journey, and it must not create “sanitary problems” or “obnoxious odors.” Otherwise it’s pretty much no problem to mail a baby alligator.

Scorpions are mailable only if they’re to be used for medical or anti-venom research, must be packed in a special sort of double-walled container, and must be clearly labeled “live scorpions.”

Warm-blooded animals, aside from those few birds, are not permitted at all. The official USPS document specifically mentions that you are not allowed to mail somebody a flying squirrel. I’m not sure if the USPS has had a problem with boxes of live flying squirrels or what.

The larger problem with attempting to mail yourself is weight. FedEx and UPS both have a 150 pound weight limit, and the USPS has a mere 70 pound weight limit. Along with the box material and survival supplies, that could make it tricky to mail oneself, if one was to ignore the very strict rules on the subject. The size of a package won’t likely be a problem; none of the three major shipping companies in the US restrict boxes to a size that would be difficult for a human to fit in. UPS, for example, allows packages up to 108 inches long, with a maximum of 168 inches in combined length and width.

Of course, it’s also unlikely you’d get away with it; security technology, especially scanners, has improved a great deal since the times of Henry “Box” Brown and even Reg Spiers. On the plus side, there’s no extra fee—you just pay by weight and how quick you want yourself to get there, and you’re on your way. Hopefully.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook