The Top Secret Cold War Plan to Bring the U.S. Under Martial Law

The War Room in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 movie Dr. Strangelove. (Photo: Columbia Pictures/Wikimedia)

A version of this story originally appeared on Muckrock.com.

Starting on April 19, 1956, the federal government practiced and planned for a near-doomsday scenario known as Plan C. When activated, Plan C would have brought the United States under martial law, rounded up over ten thousand individuals connected to “subversive” organizations, implemented a censorship board, and prepared the country for life after nuclear attack.

There was no Plan A or B.

The first known mention of this strategy was a memo released by the FBI to MuckRock under a Freedom of Information Act request. It is an invitation to the Bureau to attend an afternoon meeting on April 19, 1956, organized by the Office of Defense Mobilization.

Held in the same room as the president’s usual press briefings, just across from the White House in the Executive Office Building, this briefing requested the presence of three top officials from every department, except the Department of Justice which was asked to bring four.

It was here that the broad details of Plan C were laid out:

Officials would designate certain personnel as essential, and develop secretive remote backup offices to be used in the event of an emergency. Each of these sites was to have multiple communications links with the outside world.

The plan was to go into effect before actual war broke out, but when conflict with the USSR seemed imminent.

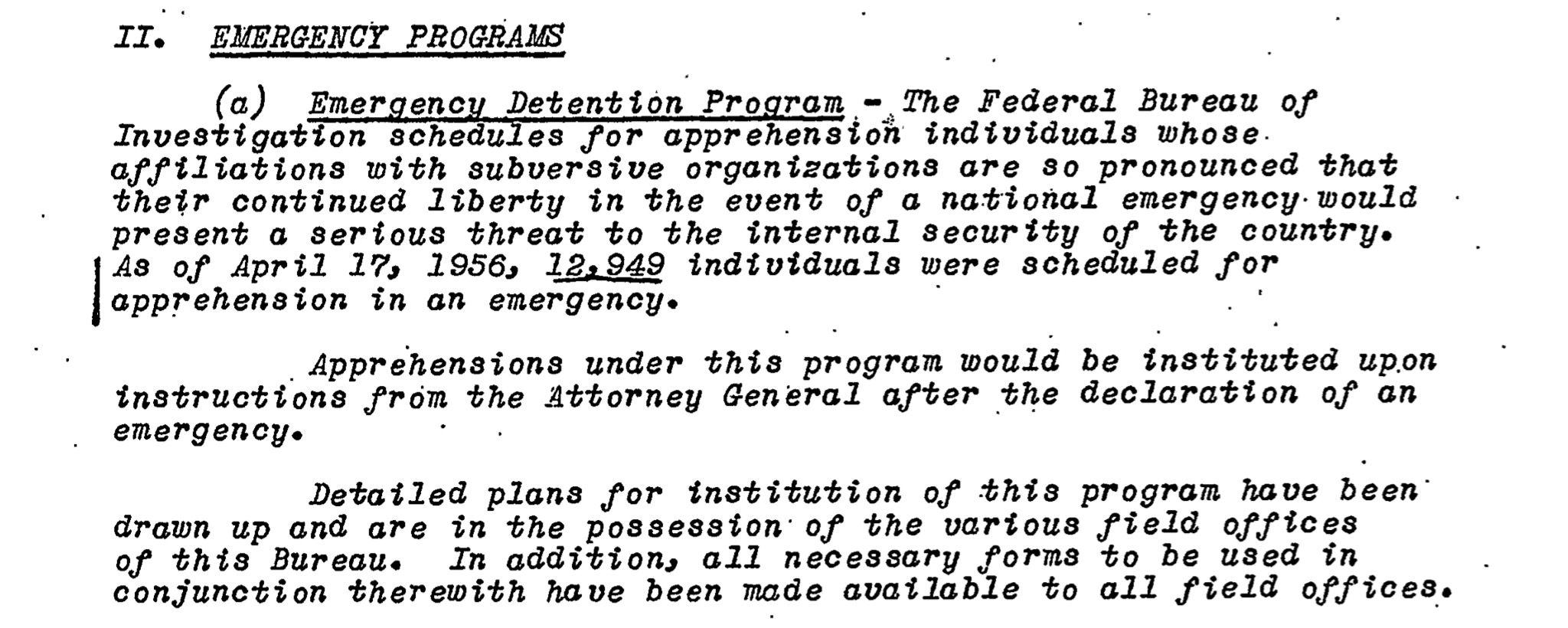

Martial law would be declared, and 12,949 individuals would immediately be detained as likely threats to national security due to their ties to “subversive organizations.”

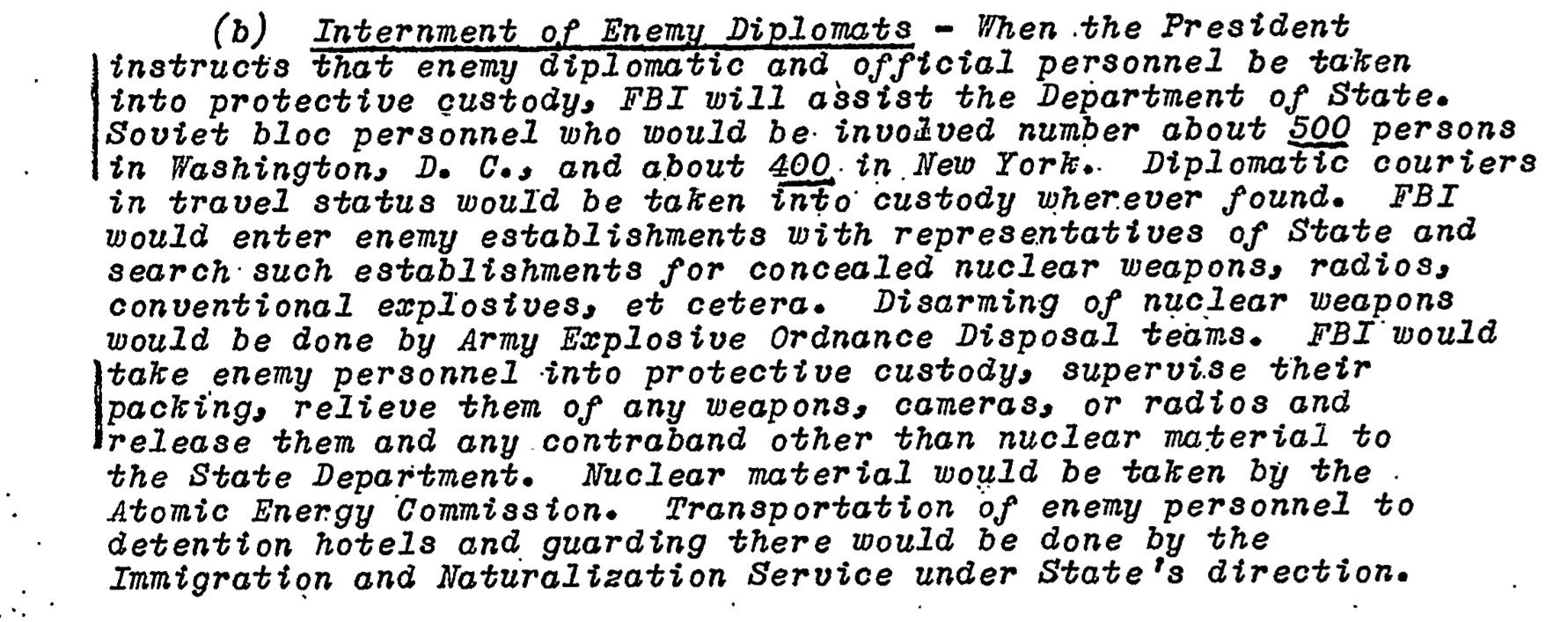

Soviet diplomats and couriers would be taken into protective custody before being handed over to the State Department. Embassies would entered and searched for nuclear devices.

Details of this program were distributed to each FBI field office. Over the following months and years, Plan C would be adjusted as drills and meetings found holes in the defensive strategy: Communications were more closely held, authority was apparently more dispersed, and certain segments of the government, such as the U.S. Attorneys, had trouble actually delineating who was responsible for what.

Details of this program were distributed to each FBI field office. Over the following months and years, Plan C would be adjusted as drills and meetings found holes in the defensive strategy: Communications were more closely held, authority was apparently more dispersed, and certain segments of the government, such as the U.S. Attorneys, had trouble actually delineating who was responsible for what.

Bureau employees were encouraged to prepare their families for the worst, but had to keep secret the more in-depth plans for what the government would do if war did break out. Families were given a phone number and city for where the relocated agency locations would be, but not the exact location.

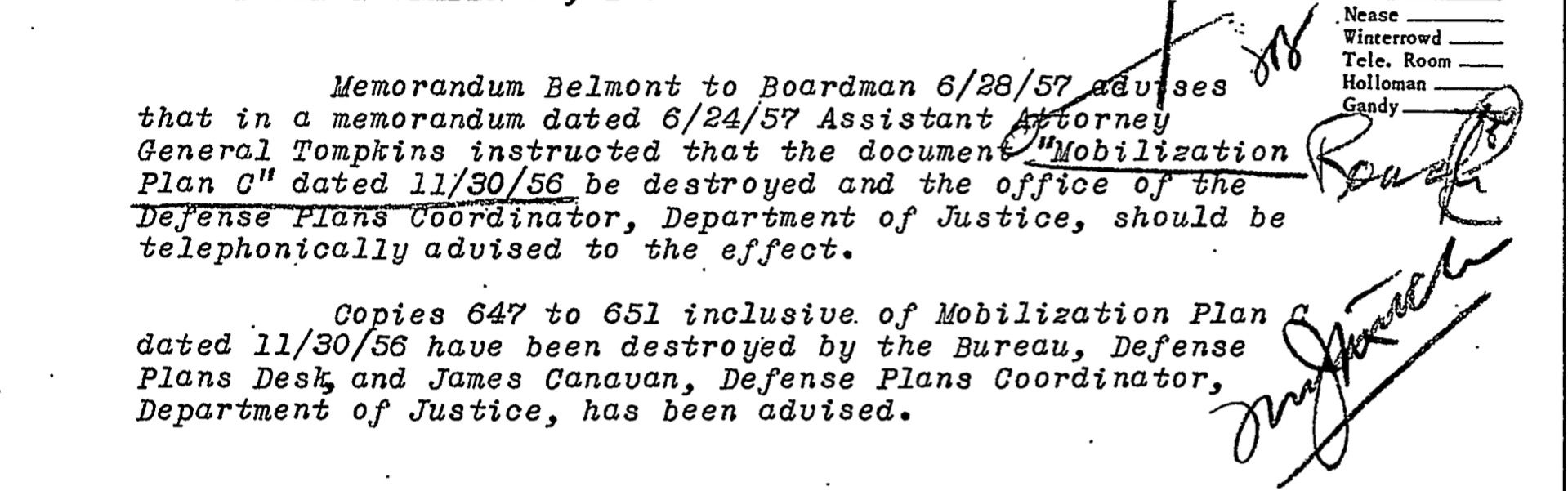

While the released memos (which were stored in the FBI’s secretive Special File Room) trace much of the general outlines of Plan C, the Plan itself was never released. A July 3, 1957, memo ordered the destruction of copies of the Plan, perhaps because they were outdated, superseded, or just too controversial. And while the FBI released about 30 pages of memos and communications regarding Plan C, there are about 150 more pages that the FBI is still processing, consulting with other departments and agencies (notably, FEMA) regarding their appropriateness for release.

One of the released sections can be found here, and you can read more on the request page.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook