How a Secret Criminal Language Emerged From the Underworld

Dictionaries made Thieves’ Cant accessible for the masses in the 16th through 19th centuries.

If you were a thief in 1700s England, and wanted to tell a fellow thief that you had spotted a naive rich man (“rum cully”) and you can’t wait to rob his house (“heave the booth”), but you don’t want some do-gooder to overhear and send you to the gallows (“nubbing cheat”)—how would you communicate this without tipping off authorities or scaring away your precious mark?

During the 16th through 19th centuries, your answer would be to speak in Thieves’ Cant. This secret language, known as a cant or cryptolect, has long since fallen into disuse. But despite its covert purpose and disputed origins, it has had a surprising impact on contemporary spoken English—in fact, you might even speak a bit like an old-time thief yourself.

Thieves’ Cant, also known as Flash or Peddler’s French, existed in many forms across Europe. The cant flourished in England during a 16th-century population boom, when less work was available amid greater competition and crime appeared to be on the rise, according to Maurizio Gotti in his 1999 book The Language of Thieves and Vagabonds. Many early cant speakers, who often were peasants or newly jobless soldiers, were considered “particularly numerous and dangerous” by more well-off groups.

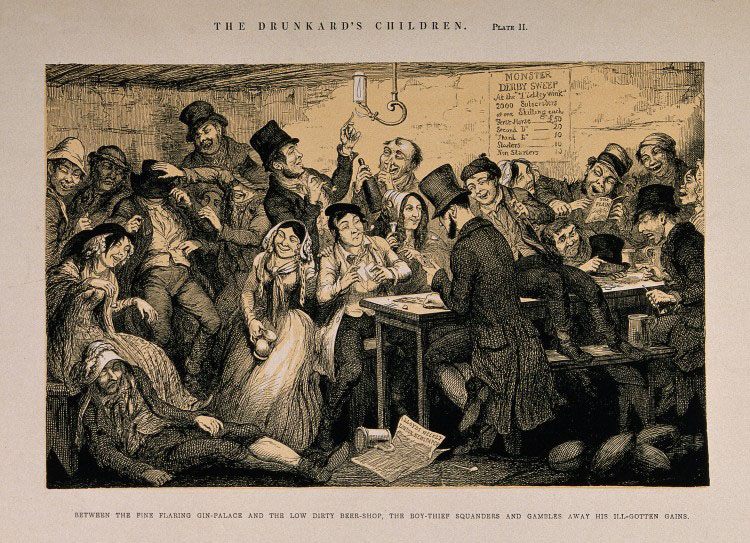

These thieves and rogues lived free, lawless lives, and met in “flash houses” (public gathering spots) to find camaraderie and share useful intel about the area. King Henry VIII announced in the early 1500s that vagabonds were ransacking the countryside, supporting reports that an estimated 13,000 “rogues and masterless men” were running amok, according to Gotti. While the number of masterless men may have been an exaggeration, their heightened visibility meant there was an increased interest in criminal activity among non-vagabonds. Those excluded from the underworld wanted to learn about it, at least partially in order to safeguard themselves.

Most Thieves’ Cant dictionaries in England were ostensibly published in order to save people from falling victim to criminals and their sneaky ways. During an uptick in crime in 1561, John Awdeley published one of the earliest English cant dictionaries, The Fraternity of Vagabonds. In a poem to the reader, Awdeley explains that the words he compiled came from interviews he conducted with men, women, and children who were “ruffling and beggarly,” on the condition that they remained anonymous, lest they be killed by their fellow vagabonds for spilling the beans. He includes short definitions and lengthy explanations of various scams to warn the public. A “ring faller,” for instance, will drop worthless copper rings in front of naive villagers, and pick their pockets when they bend down.

In 1566, not long after Awdeley’s dictionary went to the press, a man named Thomas Harman published A Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, Vulgarly Called Vagabonds. In the forward Harman writes that the dictionary was “for the utility and profit of his natural country,” and rather than publishing the words for mere entertainment, he “thought it good, necessary, and my bounden duty, to acquaint your goodness with the abominable, wicked and detestable behavior of all these rowdy, ragged rabblement of rakehells.” Harman’s book was so popular it was published several more times, including a reprint in the 1800s.

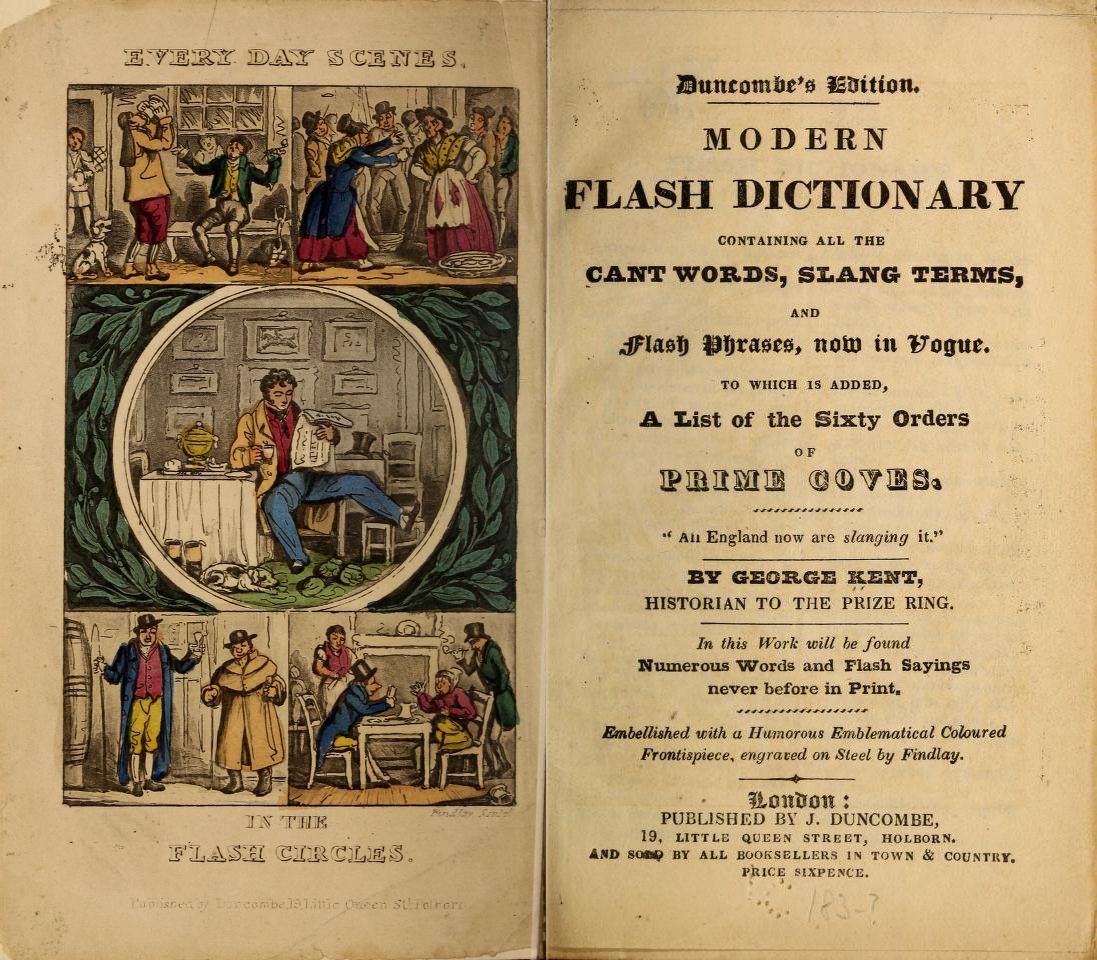

The tradition of printing updated Thieves’ Cant dictionaries spread to other English-speaking countries in the 19th century. In 1859, George W. Matsell, a police chief from New York, published The Rogue’s Lexicon to help people read criminal testimonies in public police reports, but added that many canting words “have come into general use.” Matsell’s dictionary includes words modern English speakers might recognize, such as “brag,” “gab,” “peepers,” “rat” (a cheat, as in, “to smell a rat”), “oaf,” and, the best word for face, “mug.” Even a French-English cant dictionary was published.

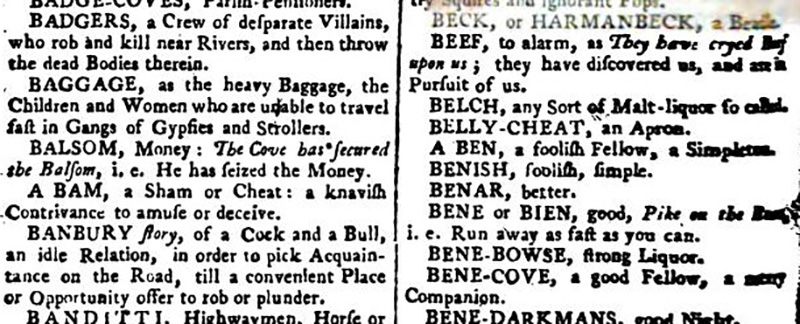

Dictionaries themselves were a fairly new phenomenon in the English language during this period, but as they began to be compiled, some included, perhaps in an effort to be more comprehensive, sections devoted to cant. The 1760 New Universal English Dictionary by Nathan Bailey, for example, has one of these sections, which includes linguistic gems such as “badgers,” defined as “a crew of desperate villains” who throw murdered bodies in a lake, and “bear-garden discourse,” defined as “common, dirty, filthy nasty talk.”

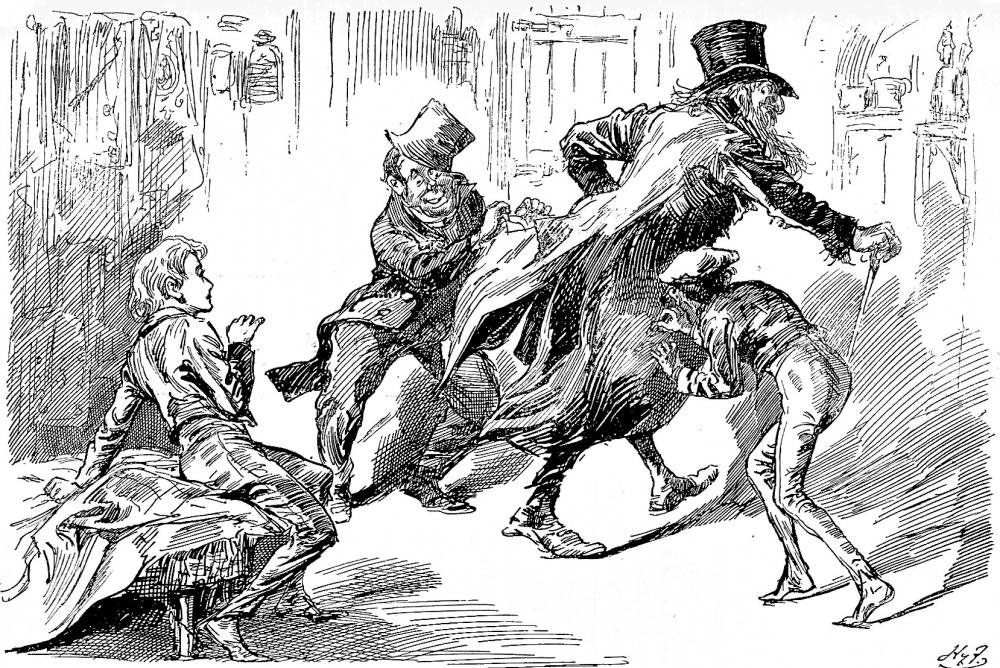

Thieves’ Cant was also popular in fiction, including famous books such as Oliver Twist, in which Oliver’s inherent goodness is apparent when he is unable to speak cant like the criminals around him. Luckily for the reader, Dickens also included a Thieves’ Cant glossary in the back.

While the exact origin of Thieves’ Cant is elusive, researchers usually regard it as a mix of English, Latin, French, Russian, Italian, Yiddish, and some versions of Romany. You can see this variety of influences in its vocabulary, which over time included anglicanized slang words such as “lingo” from Portuguese, “spado” (a sword) from Spanish, or “carouse” (to drink freely) from German. It mostly seems that in England, the syntax was based on English, and many existing English words were combined to form different meanings. For example, in some dictionaries eggs are translated into “cackling farts,” Gotti writes, because a chicken is a “cackling cheat” (with “cheat” being the cant word for “thing”), and “farts” denotes anything vulgar related to the body. “Kidnapper” (“kid,” for child and “napper,” stealing) likewise formed in the same way.

According to the literary scholar Linda Woodbridge in her book Vagrancy, Homelessness, and English Renaissance Literature, early “crime pamphlets,” short books about the lives of criminals and the poor, may have popularized the idea that all criminals spoke cant, prompting and possibly contributing to words found in the numerous dictionaries. (Woodbridge also notes that cant dictionaries include language and slang used by the poor, not just criminals.)

So many Thieves’ Cant dictionaries were published and so many references to the language existed in fiction that historians throughout the years began to wonder whether they were all legitimate. In 1890, a critic named W.W.N. wrote to American Folklore wondering if Matsell just reused English Thieves’ Cant terms, calling the words “exceedingly fishy.” As Julie Coleman, English professor at Leicester University, writes in her book A History of Cant and Slang Volume 2, dictionaries seemed to copy off one another, making word origins harder to track. For example, an entry for the word “nuts” (to be fond of) appears in a few different dictionaries surrounded by the same words and definitions. But, Gotti notes, a few court testimonies exist that “have been found to confirm the validity of the terms mentioned [in the many dictionaries he reviews in his book].” Of course, that tells us little about how frequently or how long these exact words were used.

Thieves’ Cant eventually fell into disuse after the 19th century, but it may have evolved into various other cants and slangs, including children’s songs, Cockney Rhyming Slang, and a secret language for gay men called Polari. It also inspired the creators of the Dungeons and Dragons games, which have faithfully kept (a fictional) criminal cant alive. Even modern spoken English contains echoes of the cryptolect, proving that, even after all these centuries, you can’t keep a good cant down.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook