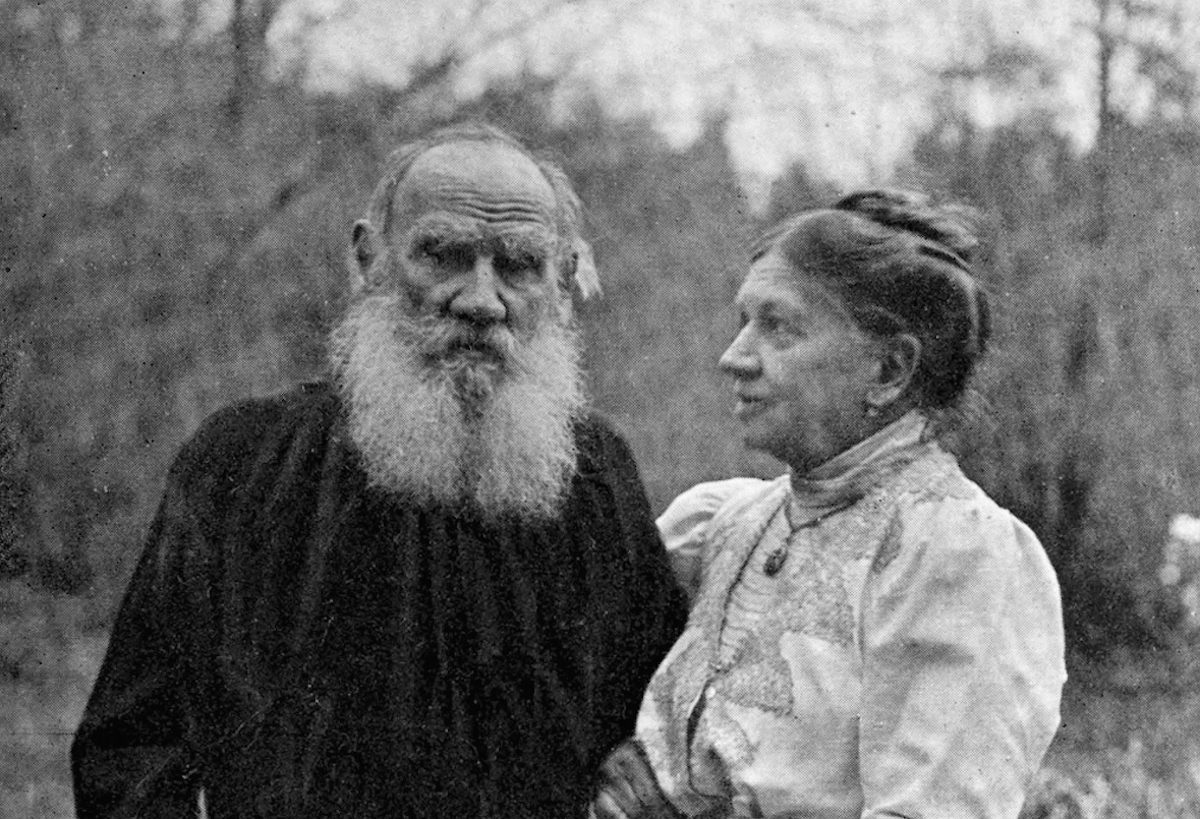

Tolstoy Ghosted His Wife Then Up and Died

But he did not get the quiet death he was seeking.

At three in the morning on a cold winter’s night—October 28, 1910 to be exact—Countess Sophia Berss woke to thumping of footsteps. Her husband, Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, arguably the nation’s most famous writer, was restlessly pacing in the next room at their home estate, Yasnaya Polyana, about 100 miles south of Moscow. He told her he had taken some medicine, asked her to go back to sleep, and shut the door behind her. When she woke again the next morning, her husband was gone.

Accompanied by his physician, Dr. Makovetsky, and dressed in rough peasant garb, Leo Tolstoy had boarded a third-class train carriage and taken off to live out his last days.

Tolstoy left behind a letter addressed to his wife, in which he wrote: “Do not seek me. I feel that I must retire from the trouble of life. Perpetual guests, perpetual visits and visitors, perpetual cinematograph operators, beset me at Yasnaya Polyana, and poison my life. I want to recover from the trouble of the world. It is necessary for my soul and my body which have lived 82 years upon this earth.”

Tolstoy had been born at the large aristocratic estate, the name of which translates to “bright glade,” but it had come to feel like a trap over the years. Soon after publishing Anna Karenina in 1877, Tolstoy had experienced a “conversion.”

“He’s a patriarch, he’s got this estate in the Russian countryside in a village that he basically owns and he goes from that to denouncing wealth—basically he has a midlife crisis, and because he’s Tolstoy, he goes, ‘I’m going to solve this,’” says Ani Kokobobo, editor of the Tolstoy Studies Journal and author of the forthcoming book Sage of Sex: Tolstoy Theorizes Gender, Identity, and Intercourse.

In the 1890s, Tolstoy retranslated and reinterpreted the Gospels of the New Testament and denounced their interpretation by the Russian Orthodox Church. “He decides you’ve got to live your life in a way that’s not very attached to the body, individuality, wealth, or sex,” says Kokobobo. So in 1901, he was excommunicated. Though still a nobleman, he began attempting to shrug off the trappings of privilege. He moved into a homely peasant’s hut on his estate, began “partaking only of the simple peasant’s food, and wearing the peasant’s costume—a rough blouse, wide trousers tucked into high cowhide boots, a leather belt, and fur cap,” according to a report in The New York Times on November 13, 1910, on his scandalous exit. He founded soup kitchens and a school for peasant children on his land, was farming, and was negotiating to release his books without copyright. He also promoted sexual abstinence, although he didn’t successfully practice what he preached on that one. In the meantime, Sophia—to whom he’d been married for 48 years and who had borne him 13 (!) children—had other ideas.

“You read their diaries side by side and they’re kind of living in different worlds,” Kokobobo says. “You can imagine how his wife is like—‘We have 13 kids and now you’re this prophet of anti-sex?’”

Tolstoy had been contemplating his death for years, but at Yasnaya Polanya he could not escape an onslaught of responsibilities as a patriarch and public figure. Even during this final journey by train, newspapers tracked his every move, presenting him as a madman all the while. He took the Kausani Railroad first, to the Shamardino Convent, where his favorite sister Maria was a nun. When his visit there was publicized, he moved on, ostensibly hoping to make it to the Caucasus. But on November 15, scarcely two weeks after leaving home, he fell ill and was taken into the train station in the little town of Astapovo. His wife rushed to his side, but was not allowed to see him until his final moments, five days later. Surrounded by press and detractors who thought him mad, it was hardly the quiet death he had longed for.

One Times article judged him rather harshly even as he was dying: “Once Tolstoy was a notable artist in the field of letters, a writer with a clear vision, remarkable powers of observation, a coherent style. Latterly he has been obviously deranged … he has gone off to die in the wilderness like a wild animal … Obvious jests will be avoided. It is very sad.”

Kokobobo sees his death as a rational extension of the spiritual ideology he had been cultivating for decades. “The irony, of course, is [Sophia] took care of him, she was his partner, she enabled his life,” she says. He had left her and his home, spiritually and physically, but he could not survive apart. “Nobody understood him and cared for him as intimately as she did. The moment he’s out of her sphere, he dies.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook