Keeping Track of Monument Removals Could Be a Full-Time Job

So data scientist Emily Gorcenski created When They Came Down to crowdsource the stories behind the topplings.

Statues have been on Emily Gorcenski’s mind for a while. Three years ago, she was living in Charlottesville, Virginia, during the tumultuous week of protests over the removal of Confederate statues and monuments, during which a white supremacist drove a vehicle into a crowd of peaceful protesters and killed activist Heather Heyer.

Seeking to track the judicial progress of hate crime cases, Gorcenski used public records to build First Vigil, a database of legal proceedings related to far-right and white supremacist violence. It’s what she does. Gorcenski is an engineer, data scientist, and hacktivist who builds online tools to track right-wing extremism.

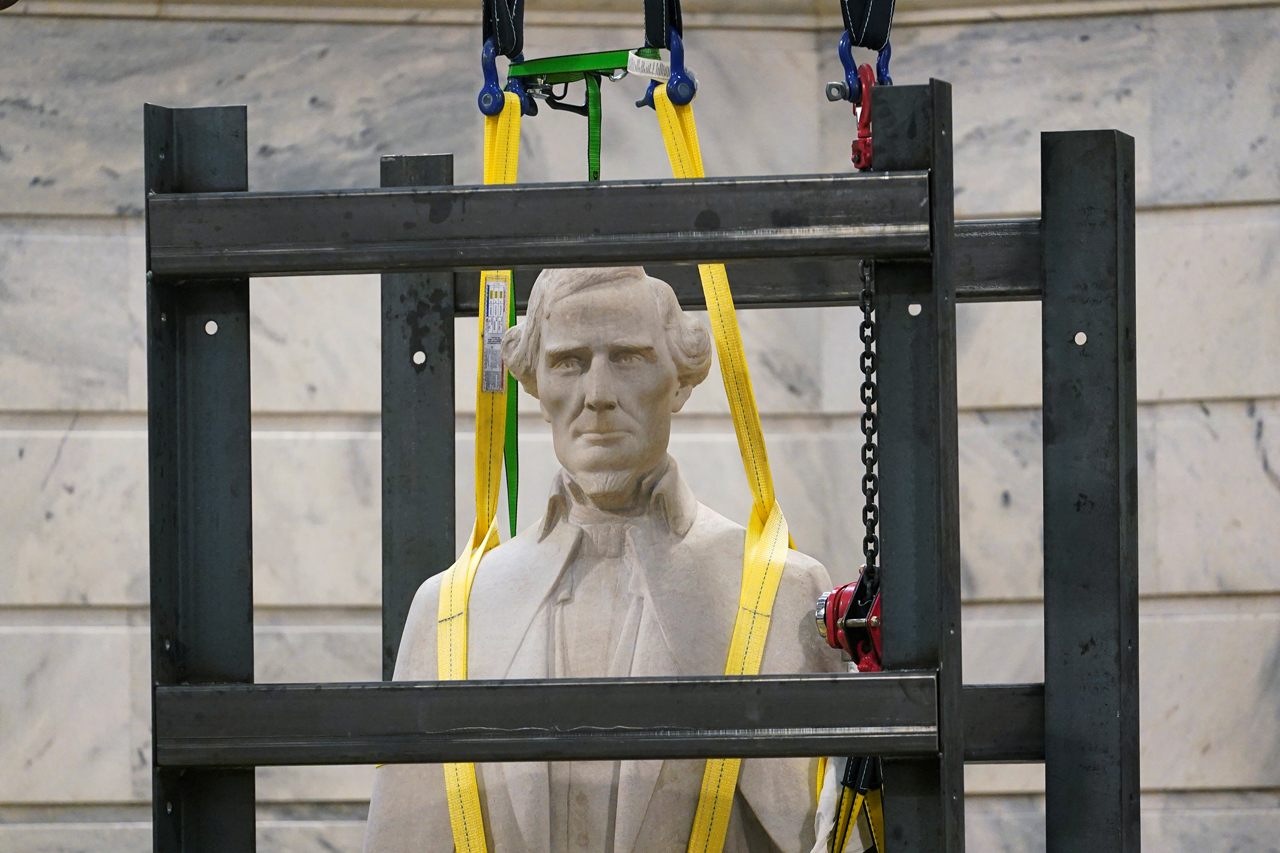

Recently, she’s been thinking about Confederate statues and monuments again, as municipal leaders and activists around the world have been advocating for the removal of offensive statues from public spaces. Her latest project, When They Came Down, is a collaborative database of statue removals.

Gorcenski currently lives in Berlin and spoke with Atlas Obscura about the catharsis of removing racist names and images from public places, and how individuals can contribute and help her maintain the growing database—a chronicle of social change and historical memory.

What prompted you to create When They Came Down?

The statue that inspired the site was the one that they threw in the river in England—in Bristol! [It depicted Edward Colston, a prolific trader of enslaved people.] The larger idea behind this project is that when statues come down, it builds and adds to rather than removes history.

I lived in Charlottesville in 2017, when there was a rally there, Unite the Right, which was ostensibly in response to statues coming down after the city council voted to remove them. Obviously, it became about other things. In the month after the rally, all around the United States, we saw something like 24 statues come down. It was a big moment, and it petered off a bit from there.

Plus, removing statues is cathartic. Charlottesville still has four deeply racist statues, and I think their days are numbered. When they do come down, that will be a great moment of healing.

There are categories and tags on the site—racists, slaveholders, and so forth. How did you choose how to classify the various people represented by these monuments?

A lot of these statues were put up to honor people who were owners of enslaved people, and who were generally racist, awful human beings. The taxonomy breaks down into broad categories, including colonizers and Confederates. People can be more than one!

I also try to classify by how the statues came down: through direct action, municipal action, or private action, such as when Duke University removed a racist statue [Robert E. Lee] some years ago.

So far, you have included at least one park that was renamed. How do you determine which landmarks to include?

I went back and forth on whether that fit, and I hesitated because it’s more work. But the renaming of places and parks is part of this larger process. In Charlottesville, for example, there are two parks that have been renamed twice in the past few years. Ultimately, I see the process of renaming places as tied to removing statues, and I’m interested in honoring that process.

How have you been soliciting submissions?

Mostly I’ve done it on Twitter, asking people to spread the word, and a bunch of people have gotten involved already, adding entries, editing content, and contributing to the technical infrastructure. That takes a lot of work off my plate.

The thing is, this isn’t a project that’s going to be done. History is a living thing. Somebody added a statue that was taken down in 1922, and it meets the criteria, so I said, “Let’s get it in there.” And, these statues are coming down in bursts. So I try to work through bookmarks, direct messages, and emails best I can. But this could easily take up 100 percent of my time.

Which submissions have surprised you so far?

I’ve received a bunch of stuff from South Africa and in places around Europe, and for me, that’s been eye-opening because, personally, I don’t know a lot of that history. It’s awesome to have more international context.

What’s your long-term hope for the project? How would you like for it to grow and serve as a historical resource?

I haven’t thought much about that yet, but this doesn’t have to be maintained or curated by me. For a long time, I have been thinking about alternatives to Wikipedia, which has a somewhat authoritarian structure about what gets included and doesn’t—as a way to share and preserve historical stories.

I’ve been overwhelmed by how many people are getting involved with When They Came Down, and how fervent they are. I really like that people are actively taking ownership. People are translating the site into Spanish, and I’d love to have this translated into 10 different languages.

One thing I’ve tried is to make this site feel like a people’s history. I want these stories to stay told. In Charlottesville, 10 years from now, I want people to be talking about how statues came down, about Heather Heyer’s death, about the rallies. I want to make sure the stories are told about Zyahna Bryant, who started the initial petition for statue removal, and about Jalane Schmidt’s walking tours. Those stories are what real history is about. People put energy into making changes in their communities, and individuals and activist organizations have been working on these issues for a long time. I want to make sure that is not forgotten.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook