Why Medieval Women Sometimes Fought in Bloody Trials by Combat

In cases of rape and sexual violence, women had few other avenues for seeking justice.

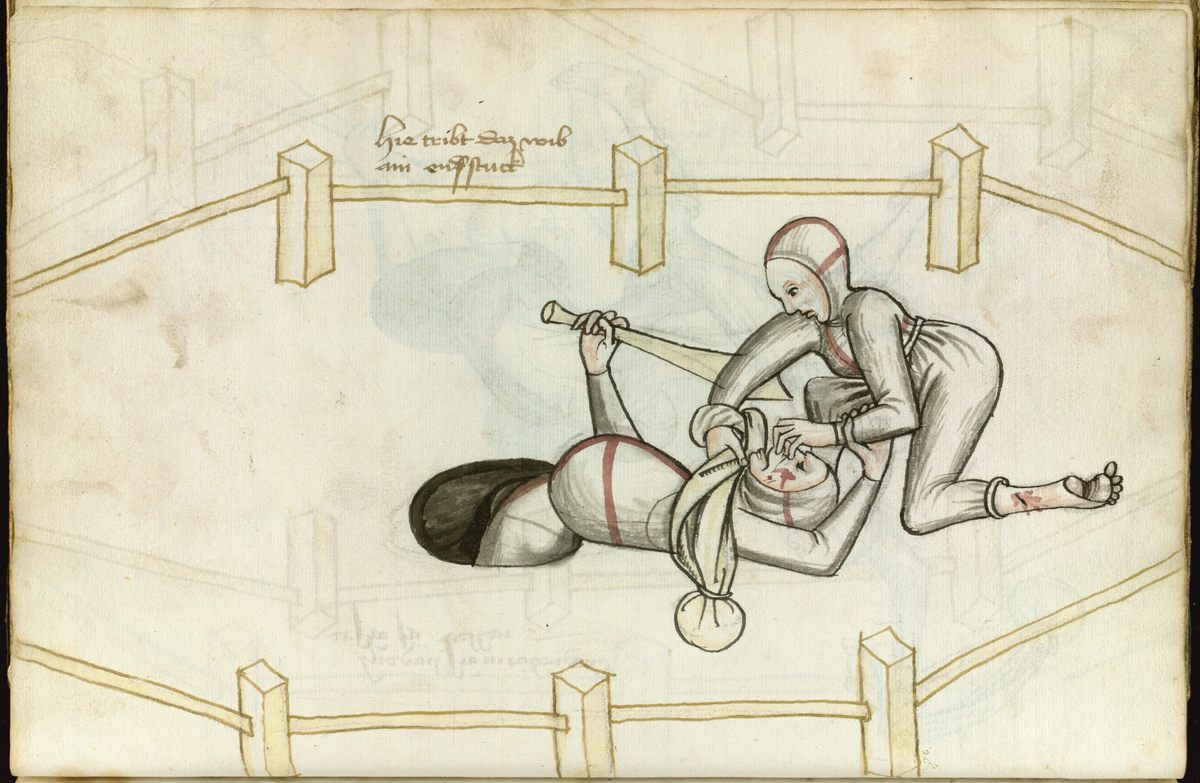

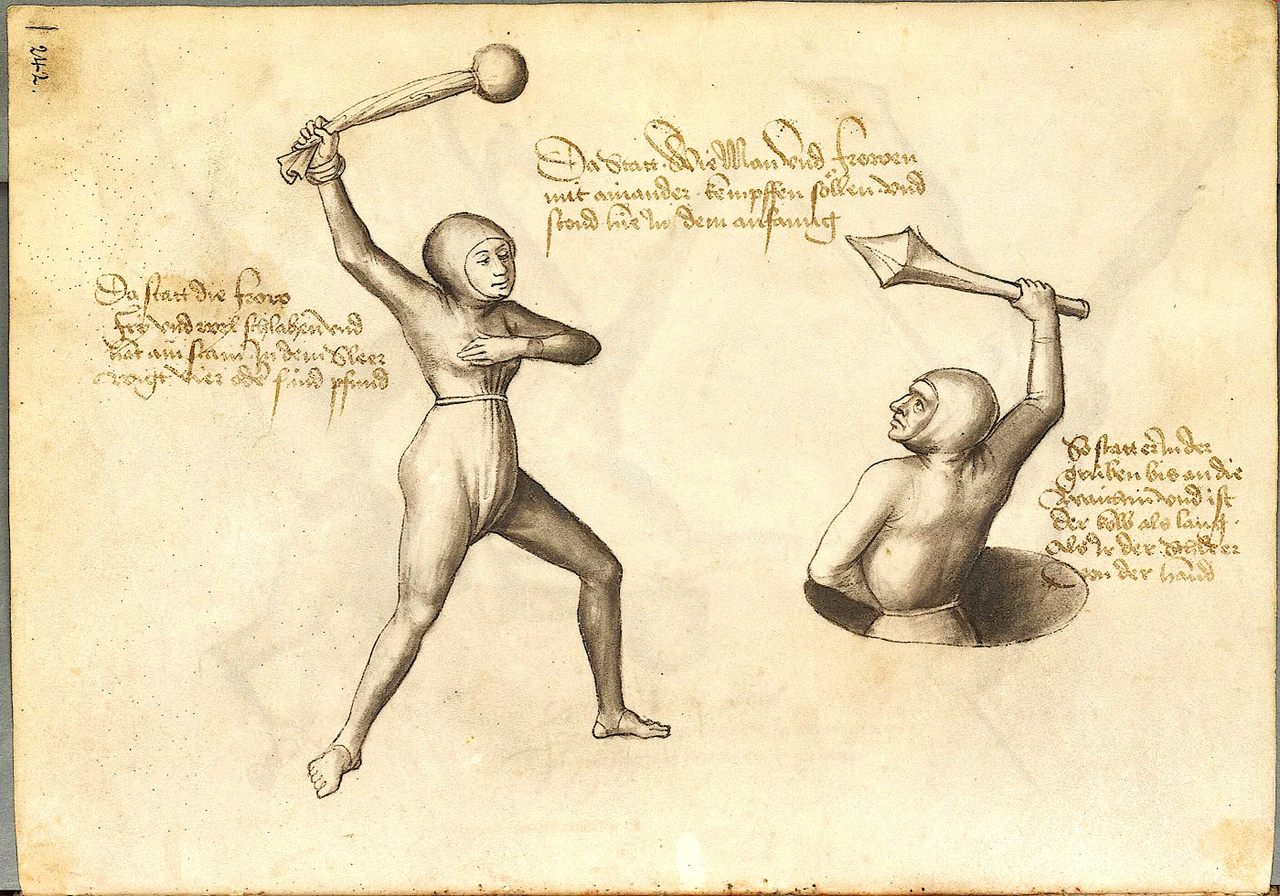

Tucked within the Danish Royal Library in Copenhagen and the Bavarian State Library in Munich, rare medieval manuscripts depict something unusual, even for the Middle Ages—a man and woman fighting in a trial by combat. The man is drawn waist-deep in a hole armed with an edged club, while the woman circulates above, flinging what looks like a rock in a sock. Both are drawn with furrowed brows, fierce snarls, and bloodied limbs.

You may have even seen these images pop up on your social media feeds on Reddit or X, with false claims that they show a legal recourse for medieval German couples seeking divorce. However, the truth behind these images is far darker and more complex. Based on obscure 13th and 14th-century German, Austrian, and Swiss laws, these images show trials by combat, known as judicial duels. The legal face offs were used to resolve complex rape and sexual assault charges. While trials by combat may seem far removed from modern law courts, they underpin how difficult sexual crimes can be to prosecute—both in the Middle Ages as well as today.

Rape was considered a serious crime in the medieval world, says Albrecht Classen, a German studies professor at the University of Arizona. If a rapist was found guilty in court, they were immediately sentenced to death. “It was a crime, a severe sexual crime, and there were consequences: prosecutions and executions,” says Classen, who also wrote a book on the topic, Sexual Violence and Rape in the Middle Ages.

Legal records show that sexual violence against women was the main, if not the only, kind of sexual crime dealt with in medieval courts. (Undoubtedly, other sexual crimes occurred in the Middle Ages, but sexual violence against women has the clearest documentation.) In a rape trial, the burden of proof fell on the victim, and without concrete evidence, a conviction was nearly impossible.

While today we rely heavily on DNA testing in rape trials, in the Middle Ages a woman was required to scream during her assault to draw public attention and witnesses who could later testify on her behalf, says Classen. In cases of unwitnessed rapes of young women, the court could summon a female medical examiner to inspect her hymen. Both types of evidence had obvious pitfalls.

According to 13th and 14th-century legal treatises, judicial duels between men and women only happened in cases of notnunft. The medieval law term describes rape, kidnapping, and sexual assault committed specifically against women, says Ariella Elema, an archivist and legal historian specializing in these duels. Medieval courts often turned to trials by combat to decide unwitnessed sexual crimes, such as notnunft, that lacked straightforward evidence, says Elema.

A 1276 law from Augsburg, a Bavarian city some 150 miles northwest of Munich, specifies that a woman could bring an accusation of an unwitnessed rape against a male perpetrator in court. However, the man could clear himself if he swore an oath of innocence. This left the woman with two options: accept the oath or fight to the death in a duel, says Elema.

If she chose to fight, the man would stand waist-deep in a hole, armed with an oaken cudgel, while she circulated above with a fist-sized stone in her sleeve. Whoever lost was buried alive.

Fast forward to 1328, and a Bavarian law book adds that the man’s left hand must be bound behind his back. If he lost the duel, he was declared guilty of the crime and beheaded. If the woman lost, her hand was amputated—a punishment for committing perjury.

While judicial duels were used to settle many legal issues, they rarely happened, says Elema. Instead, the threat of duels often pushed parties to negotiate a non-violent settlement. For sexual crimes, trials by combat were intended to discourage women from bringing unwitnessed rape accusations before a court.

“Lawmakers today still struggle with how to prosecute rape. In many cases, there is simply no way to provide sufficient evidence for a conviction, so the victim is left unsatisfied and humiliated,” says Elema. “The philosophy of medieval courts seems to have been: ‘Well if you want to tempt God and try for divine intervention, we will leave you one extremely difficult way to prosecute this yourself.’ In a way, they were recognizing the limitations of their own system.”

The only example of a judicial duel being used to settle a rape accusation in medieval Europe was in the Swiss capital of Bern in 1288. Despite all the odds stacked against her, the woman emerged victorious against her male rapist. Although records are sparse (medieval chroniclers were notoriously tight-lipped about the case), a 1484 chronicle by Diebold Schilling the Elder dedicates a single page to the duel. Schilling wrote, “In the year 1288, as man counts, on the 8th day of Kindlen, a duel occurred in Mattequartier [a neighborhood in Bern], where the wall of the church cloister now stands, and a man and a woman dueled with one another, and the woman was victorious.”

Elema believes the anonymous woman’s victory helped spread knowledge of these types of judicial duels throughout Europe. So much so that centuries later she was immortalized in 1459 and 1467 illustrations by the 15th-century German fencing master Hans Talhoffer (the same illustrations that have recently circulated online). “I think she was living rent-free in a lot of men’s heads for two whole centuries” before Talhoffer drew her, says Elema.

In the 15th century when Talhoffer drew his images, judicial duels were still—at least theoretically—in use, and fencing masters would exploit the threat of these duels to attract new clients.

Michael Chidester, the editor-in-chief of Wiktenauer, an online community research project about European martial arts, says manuscripts like Talhoffer’s were created for various reasons. “Some texts were created by masters for specific students as memory aids,” he says. “Other texts were created as prestige objects—usually lavishly illustrated” for noble clients. Only 36 such manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries, including Talhoffer’s two, have ever been documented.

Although Talhoffer never witnessed a judicial duel, his illustrated fight sequences are extremely detailed, likely inspired by staged reenactments and surviving scraps of knowledge, says Elema. But all sources have their limitations, she says, and Talhoffer’s images are no different.

“You’re working from a medieval source that’s working from an even older medieval source. So that’s the question: how far is this reconstruction kind of devolving into its own fantasy land?”

For Classen, these judicial duels help illustrate complex medieval gender structures that, in many ways, echo modern ones. Despite centuries separating us from the Middle Ages’s judicial duels, our modern legal system still echoes the past. Rape cases continue to be notoriously difficult to prosecute and the onus of proof still too often falls on victims of sexual violence.

“Those who do not pay attention to the history of women, in all of its complexity, it means they are fighting a foolish fight,” says Classen. “The social struggles that we face today, say racism, rape, and misogyny, are continuations of the past.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook