Toys Are Taking Vacations and Seeing the World (Without Their Owners)

A social media trend has spawned travel agencies and even passports—just for stuffies.

Sonoe Azuma was four years old when she got her first stuffed toy. “An American woman who worked for the U.S. Air Force base in Japan used to live next door to us,” she says, “and she gave me a big Snoopy as a Christmas present.” The stuffed beagle became an inseparable companion throughout her childhood in Japan, something like “a friend or a little brother.” It’s not an unfamiliar feeling to anyone who grew up with a favorite stuffie.

Azuma grew up, but as she got older, she rediscovered a passion for soft toys. This time it was a handmade eel, which she named Unagi (“eel” in Japanese), that she took with her on trips. She just thought it was fun. “I blogged the photos and made my friends smile and made me smile,” she says. “I thought it was a fun and creative way to share my daily life.”

Azuma isn’t alone—lots of adults make toys a centerpiece of their travel dispatches. In 2014, Shanna Robinson, a graduate student at Western Sydney University’s Institute for Culture and Society, saw a trend worthy of study as part of her doctoral research. “When I started chatting to people about the practice of taking a toy traveling,” she says. “I was shocked at how widespread it was. Almost every person I spoke to knew someone who had taken a toy traveling.”

Robinson, whose interest in the topic was inspired by a chapter on “traveling mascots” in the Lonely Planet Guide to Experimental Travel, a compendium of unusual travel ideas, spent months studying the Flickr community “Traveling Toys.” Founded in 2005, the group now has 2,498 members and 47,600 photos.

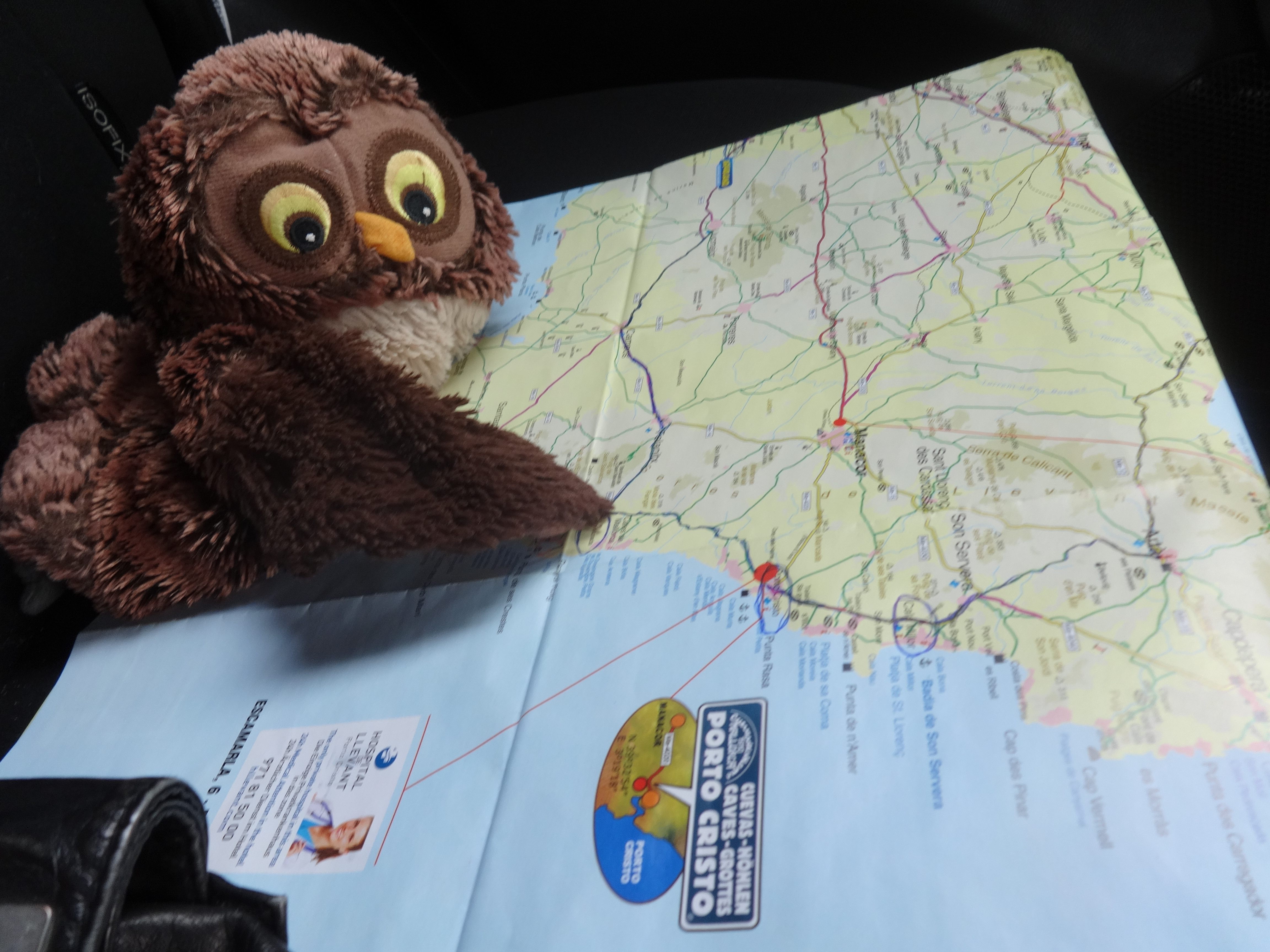

For her study, Robinson analyzed a sample of images and asked members to fill in a short survey about their travel behavior. She then identified some common trends, such as the desire to “accumulate travel culture capital” by sharing pics of toys posed in world tourism hotspots. Think Dexter the toy chipmunk at Monument Valley, a panda bear strolling through Red Square in Moscow, a teddy checking out Stari Most in Bosnia.

It “highlights the connection between the phenomenon of the traveling toy and broader cultural logics of tourism,” Robinson says. Something about pictures of toys by famous world landmarks makes a certain breed of traveler feel particularly worldly—the familiar and the foreign together, as if it is the most natural thing in the world.

After a while, Azuma’s friends started asking her if they could take Unagi with them abroad, and they began sending photos of the eel beside famous landmarks as well. “Seeing Unagi in Paris or New York while I was in Tokyo was inspiring and fun,” she says. “It was a way to see a different part of the world.”

Soon she realized that the concept might appeal to a wider audience. So in 2010 Azuma quit her job in Tokyo’s financial industry to start a travel agency—not just any travel agency, but one that caters exclusively to stuffed animals. “At the beginning people thought it was a crazy idea—who would pay for this?—but I knew that this would make people who can’t travel, like disabled kids, old people, or low-income families, smile.” She decided to name it after its inspiration. To date, Unagi Travel Agency has organized trips for more than 100 stuffed animals, many of which have become repeat customers. Prices for trips vary depending on the destination, but standard tours of Tokyo and its surroundings go for around $50.

Clients ship their toys to Azuma, and they stay with her for two or three weeks, during which time their adventures are promptly reported back to their owners via social media posts. At the end of the tour, Azuma ships them home. Tours include visits to the capital’s most iconic landmarks, as well as a variety of other activities. “I take them to yoga classes, soccer games, marathons, or visiting car factories, like Mazda, as I think they [the clients] enjoy these activities more than just sightseeing or eating out at restaurants.”

This is in line with another trend identified by Robinson, anthropomorphism of toys in poses that imitate human behavior. “From poses to accompanying captions, there was a clear trend of toys appearing to experience travel [like real people]. The toys were photographed worried about missing public transport, deciding on their next meal and, of course, posing in front of famous tourist sites,” she explains.

For example, one caption below a teddy bear riding the Eurostar train from London to Paris read:

I made it onto the train! There was a bit of drama where I got separated from my travelling buddy in the London Underground, but we got it together in the end. Also, they gave me breakfast on the train! And I got a nice view of the English countryside on my way to France.

Before taking the cuddly companions out, Azuma asks their owners to fill out a short questionnaire. She relies on these to inform the trips, but also goes with her gut. “Last week I had a rabbit, Dennis, joining from Washington in the U.S. I wasn’t sure if he liked Japanese food, but I felt he was enjoying it, so I expressed that in the photos and videos I shared,” she says. “Maybe half is based on the profile, but half is imagination that comes from communicating with the stuffed animals.”

To Azuma, this kind of relationship with toys is actually something that can help people struggling with anxiety or depression. She shared the story of a boy who had stopped going to school after being bullied. “His mother was worried to see her son just staying at home with no connections with the outside world. She sent his stuffed animal on a trip and he enjoyed seeing the outside world and seeing his stuffed animal getting along well with other stuffed animals. Eventually, he became interested in going outside.” After the trip, the boy went to visit Azuma with his mother, and eventually returned to school. “Now he’s a high school student. He’s still shy and has some challenges, but he’s attending classes.”

Of course, taking photos of stuffed animals over dinner or on the subway comes with its own challenges, such as looking weird to the uninitiated. “When I took my first customer, Lars, a gorilla from Hawaii, on a tour of Paris, I was worried of what people could think about taking photos of such a peluche [French for ‘stuffed toy’],” says Sabine Passelegue. Passelegue, inspired by the trip her daughter’s stuffed bee took with Azuma, opened a similar service, called Peluche Travel Agency, in France, with Azuma’s blessing.

The Frenchwoman has since taken around 50 guests on more than 40 tours around France. Her most regular customers are older people who can not travel anymore and are happy to explore the world vicariously. “For me, the best part of the job is to share what I see,” she says. “It’s a pleasure to allow people to discover my country and its lifestyle.” She admits that she still worries about people looking at her like she is “quite crazy with her peluches,” but most of the time, people share her joy—even police on the Champs-Élysées.

Robinson doesn’t know for sure when the toy-travel trend began (the gnome in the movie 2001 French film Amélie may have helped popularize it), but in the last decade social media platforms have led to the birth of something like a toy-travel ecosystem. In addition to the agencies in Japan and France, there is now Toy Voyagers, a website that connects traveling toys with hosts, and Omanimali, a toy-passport-issuing organization based in Germany.

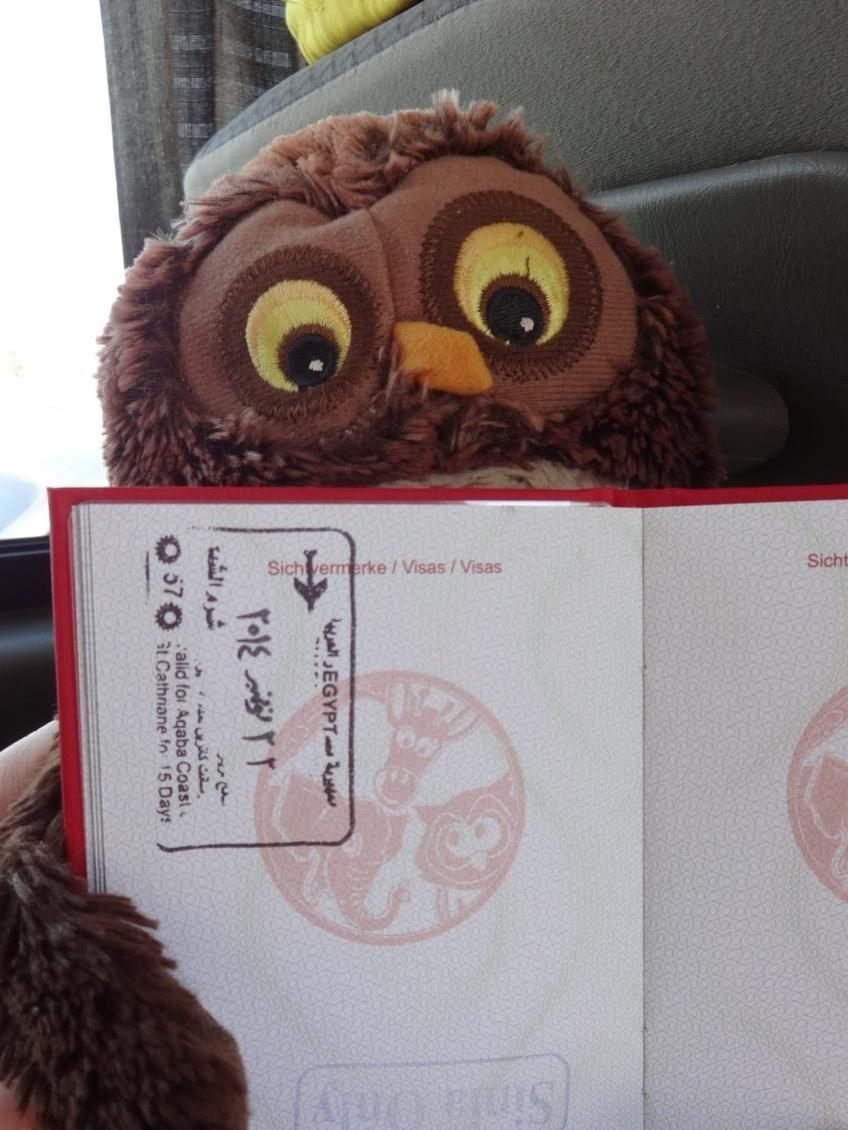

“Back in the 1990s I was traveling in Asia with my stuffed animal, Illigel, a hedgehog glove puppet, and a friend gave me a sort of passport he had, which I turned into Illigel’s passport, with her photo and data,” says Stephanie Tuschen, who founded Omanimal in 2013. “It was quite fun and even though I was already a grown up by that time.”

To date, Omanimali has issued 852 passports. The first one was tested with the German Federal Border Guard at the Munich airport. “They had so much fun with the passport that they ordered one for the teddy bear they keep in their office,” Tuschen says. In fact, several of her clients tell stories of dour immigration officers, and how the toy passports tend to break down their serious veneer. More often than not they actually stamp the passports.

Tuschen says that the idea is really about emotional connection and finding a different way to look at the world. This echoes what Robinson ultimately found most important in her study of the trend. When people see the world through the eyes of their toys, it can seem “fresh, new, exciting, and most of all, unique. After all, isn’t that what we often seek and crave when we set out to travel?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook