The Victorian Ladies Who Smuggled a Mummy Case Out of Egypt

And did the unthinkable to the mummy inside.

At first glance, the cartonnage in Macclesfield Museum’s display of Egyptian antiquities seems like any other mummy-holding case. The cartonnage material is made of two or three thin layers of bandages applied on top of one another, with ancient glue holding them together. It’s “the Egyptian equivalent of papier mâché,” according to Ken Griffin, Egyptologist and Curator of the Egypt Centre at Swansea University. Its smooth surface, created by a thin layer of plaster, is painted with images to guide the deceased to the afterlife in shades of salmon pink, blue, and olive green. It once held mummified remains and was placed inside a sarcophagus.

But if you lean in very close, you might notice that this cartonnage has a couple anomalies. A pair of orthogonal seams are barely visible: one runs around the base, and the other bisects it around the waist. These are evidence of repairs made after the case was cut into pieces—and the mummy removed—for smuggling. And the people who pulled off the illegal heist were two Victorian ladies.

Though the cartonnage dates to about 800 BC, it was taken from Egypt in 1874. “[The cartonnage] is special because of what it tells us about the actions of British travelers in Egypt at that time, as well as for its own sake,” says Bryony Renshaw, Macclesfield Museum’s Collections Officer.

Macclesfield, a market town in northwest England, seems an unlikely spot to find a collection of Egyptian antiquities. But the artifacts are here because of Marianne Brocklehurst, the daughter of a wealthy silk mill owner, and her interest in archaeology.

In November 1873, 41-year-old Brocklehurst departed for Egypt with her companion, Mary Booth. Together, they were known as the “MBs.” This was their first of five Egyptian expeditions, from which they returned with artifacts that now furnish Macclesfield’s Museum.

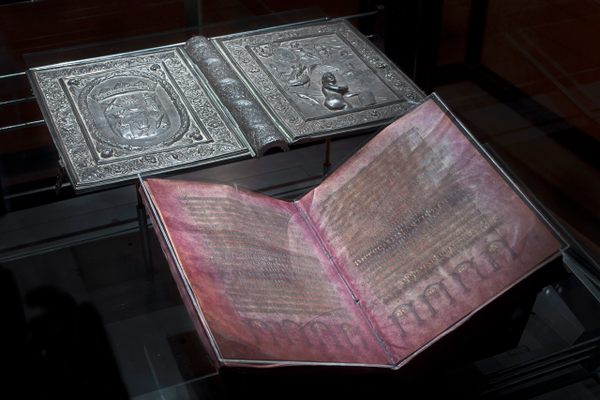

Brocklehurst documented their travels in handwritten notes, sketches, and watercolors in her diary, which is also housed in the museum. It is clear she wanted to procure Egyptian artifacts and deliberately shun the legal route in doing so. Brocklehurst explained how she acquired the cartonnage in an addendum to the diary called, “How We Got Our Mummy”.

In Alexandria, Brocklehurst met an artist who knew locals in possession of antiquities. By sheer luck, after sailing down the Nile and stopping at archaeological sites along the way, the MBs bumped into the same artist among the ruins of Thebes. After having dinner together, under nightfall he led them to a tomb, now the residence of a local family. Within one of its chambers, the family presented them with a sarcophagus. Brocklehurst declined to take the whole thing due to its size, but instead negotiated for just the cartonnage inside.

A tense couple of days ensued, while the MBs awaited the mummy case to be smuggled to the opposite side of the river, whereupon two of their party were to row across and collect it. On the first night, the two set off before hearing gunshots in the distance. Although they didn’t know the source, they hurriedly abandoned the attempt.

The second time was successful, and they stowed the case in the MBs’ cabin. Brocklehurst later described how Booth sawed the cartonnage open around the base and their subsequent disappointment on discovering it contained only mummified remains and no accompanying treasures. Worrying that the cook, who had worked for an archaeologist, would recognise the distinctive scent, they disposed of the mummy. Brocklehurst’s allusion to this at the time in the diary states, “That night, the last act in the M. is performed.”

Brocklehurst wrote little about the events at the time and only recorded the mummy’s fate in code, likely from fear of getting caught. “It’s only in the addendum to the diary, which seems to be written after she got back from Egypt, that she goes into any detail about objects,” says Renshaw.

Griffin explains that taking large, valuable antiquities out of the country without a license was illegal. “If [Brocklehurst had] brought it to the Egyptian authorities, she probably could have got an export license and paid whatever amount it was in order to get it,” he says. But it seems illegality must have been part of the thrill for the MBs.

The addendum contains Brocklehurst’s blatant intent. She wrote that the size and weight of the cartonnage’s wooden sarcophagus rendered it “out of all question from a smuggling point of view,” adding, “we liked the idea of smuggling on a large scale under the nose of the Pasha’s guards who, as excavations were then going on near at hand, were pretty thick on the ground and on the alert.” It is within this section that we also learn the mummy’s true fate: “[It] was buried by night with great secrecy and left in his native land.”

Renshaw says the MBs had a real enjoyment of trying to defy expectation and do things that people thought they shouldn’t be doing because they were women. “I think they saw it as a sort of intellectual challenge to try and outwit all the authorities… which obviously from a modern perspective is quite shocking, but that’s the interpretation that comes across to me in the way that [Brocklehurst] writes about the whole episode.”

The diary makes no mention of the cut across the waist of the cartonnage, which Renshaw says would have been done to make it easier to smuggle. Nor does it mention the subsequent repair job. Both only became apparent in 2018, when the cartonnage was moved from a low-lighting environment at a previous site. “We started to notice that actually there are these strips that run around the outside and the waistline of the case… the paint(s) used on the strips are similar in color but not quite identical to the color on the rest of the case.”

Brocklehurst later became a supporter of the Egypt Exploration Fund, which was created to preserve Egyptian monuments, and supports and promotes Egyptian cultural heritage research projects to the present day. Still, to a modern gaze, cutting up artifacts, disposing of mummified remains, and smuggling relics is sacrilegious. Griffin explains casually handling artifacts was commonplace at the time. “From the 1850s or so, local Egyptians are selling objects. They’re breaking up and sawing up coffins, and they’re selling them to tourists,” he says. “A lot of people would often bring back the head of a mummy—not the whole body, but just the head—because that was the thing to do.”

It’s unclear if the pilfered object will ever be returned to Egypt. Much was taken out of the country at that time, mostly via antiquated licensing laws, but as Renshaw points out, this collection involving two audacious Victorian women is “quite unusual.” The whole account is preserved in the diary in Macclesfield, which today rests very close to the protected, nearly 3,000-year-old cartonnage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook