Getting to Know Edward Gorey

A visit to the home museum of the famous oddball artist, 30 years after meeting him there for tea.

On a June day too dank for the beach, a three-generation carload of Goreyphiles—fans of the American author, illustrator, and oddball genius Edward Gorey—pulled into a small parking lot in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts.

The Edward Gorey House, a sea captain’s home the artist bought in 1979, is now a museum that welcomes visitors from April to December each year. Gorey slowly reclaimed it from rot and ancient plumbing, and lived and worked here until his death in 2000. I was the senior member of the group, and one with a history here, a history that involved Gorey himself.

“Look, it’s The Doubtful Guest!” yelped my daughter, immediately spotting a familiar figure. A metal sculpture of this favorite mischievous Gorey character stood on the lawn, complete with natty scarf. I’d call it larger than life, but what is life-size for an invented, rather avian creature in sneakers?

The youngest of our group, my five-year-old granddaughter, already raised on Gorey’s strange little books, had heard that he cohabited with half a dozen cats and wondered whether there were any still about.

I had seen them before.

In 1991—when the house was so overgrown by lilacs and clematis that its owner, providing driving directions, had warned that it might look abandoned—I had tea here with Gorey. And his cats.

I was then a Washington Post reporter, and a visiting ballet company was performing The Gilded Bat, based on a Gorey book, at the Kennedy Center. I volunteered to write a story, mainly because I wanted to meet Edward Gorey.

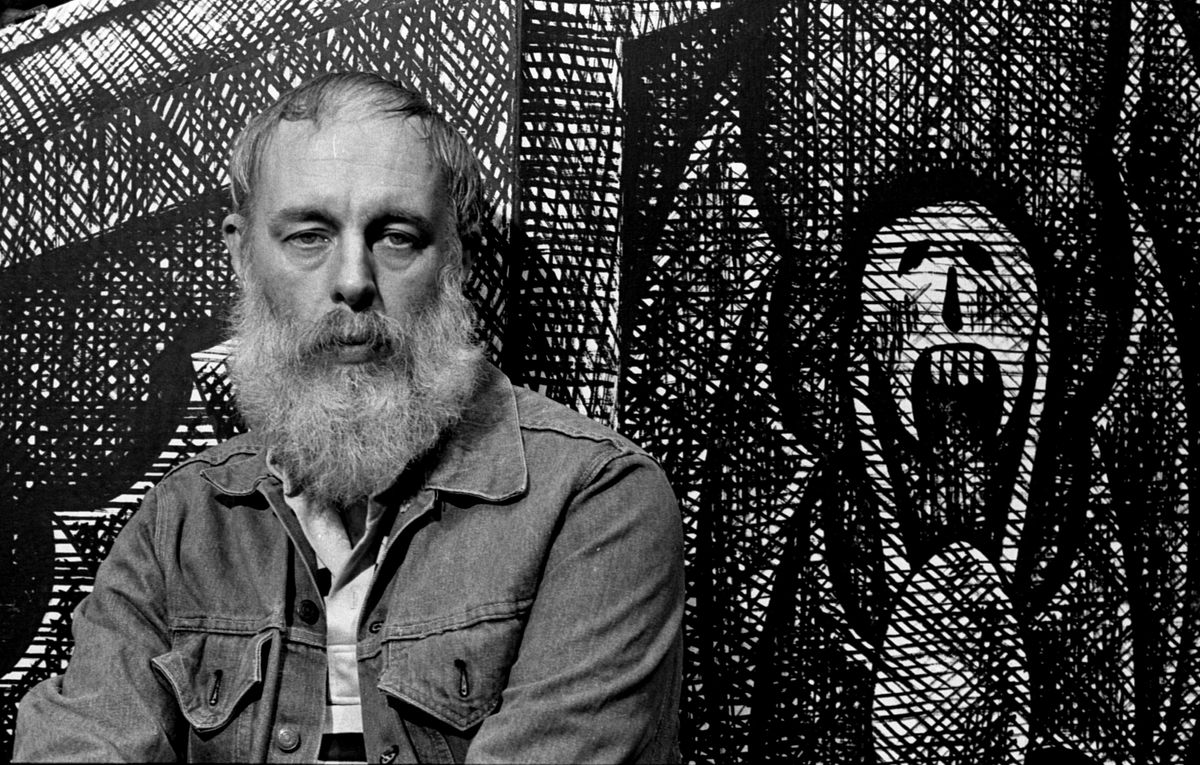

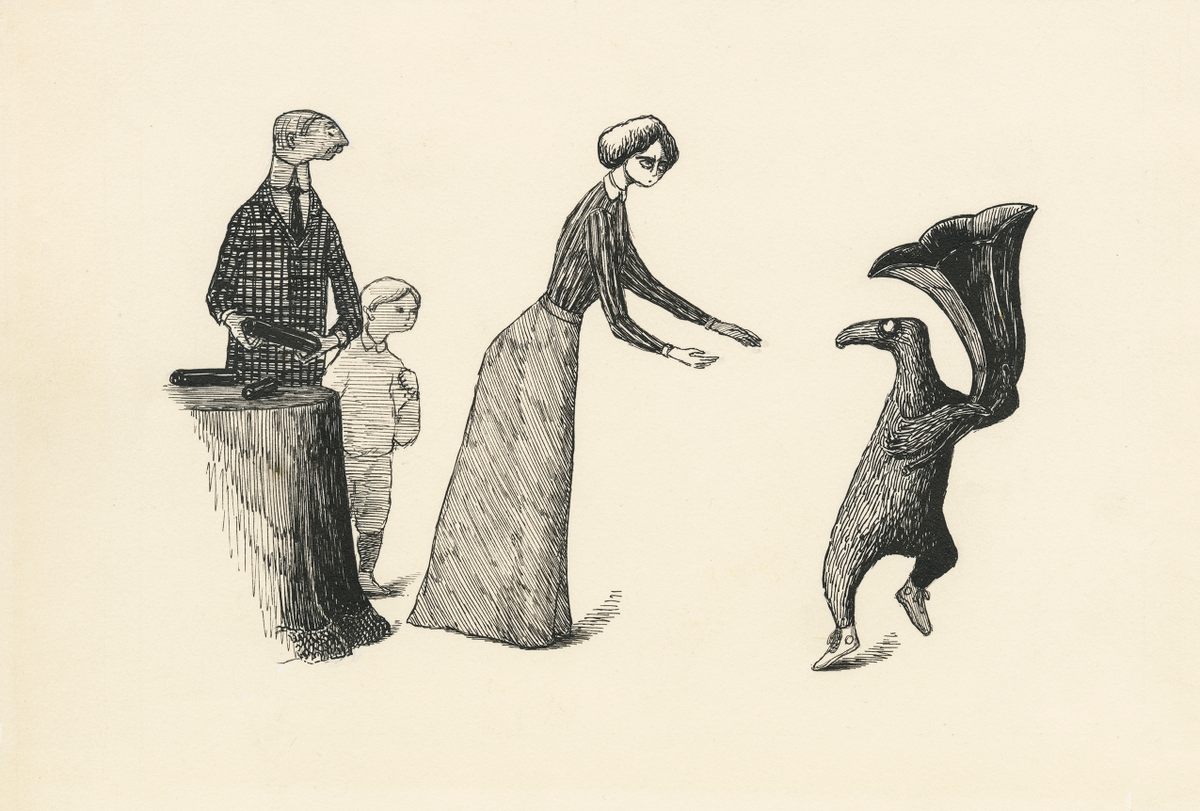

He had become a somewhat-beyond-cult figure, known for his intricately cross-hatched drawings of vaguely Victorian figures, often suffering ghastly fates, and for the droll stories accompanying them, often in rhyming couplets: The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Wuggly Ump, The Evil Garden.

His introductory animation to the popular public television series Mystery, featuring more ghastly fates, helped bring him a broader audience, as did his illustrated version of T.S. Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (source of the musical Cats).

For years, New Yorkers looked for him at Lincoln Center, where he attended virtually every performance of the New York City Ballet— in a full white beard, sweeping fur coats, white sneakers—until he left urban life behind and moved to Cape Cod full time.

It could be argued that Gorey is even better known now, 22 years after his death at age 75.

The Edward Gorey Charitable Trust, established in his will, has been archiving and showcasing his work, and striking deals for film and television. His books remain fixtures on store shelves. The Trust even launched a fans’ letter-writing campaign to honor Gorey with a U.S. postage stamp in 2025, the centennial of his birth.

His former home draws about 10,000 visitors annually and helps support that legacy-building. It’s almost as quirky now as it was then, when he hung bat houses on the trees outside, because, he told me, “I love bats. I don’t know any bats, but in principle.”

Small wonder Gorey loved bats. “It’s the house that Dracula built,” said our tour guide Gregory Hischak, who turned out to also be director of the Edward Gorey House. Among Gorey’s laurels is a Tony award for the costumes for the musical version of Dracula, which opened on Broadway in 1977, starring Frank Langella. Gorey’s royalties for the costumes and set design allowed him to buy this semi-derelict property for $84,000 and install central heat, a new roof, and modern wiring.

It looks much spiffier now. On my previous visit, paint was flaking off its wooden shingles. The floors, half-covered by enormous piles of books, had tilted in different directions. Today, the 26,000 volumes have been carted away and the floors no longer induce vertigo.

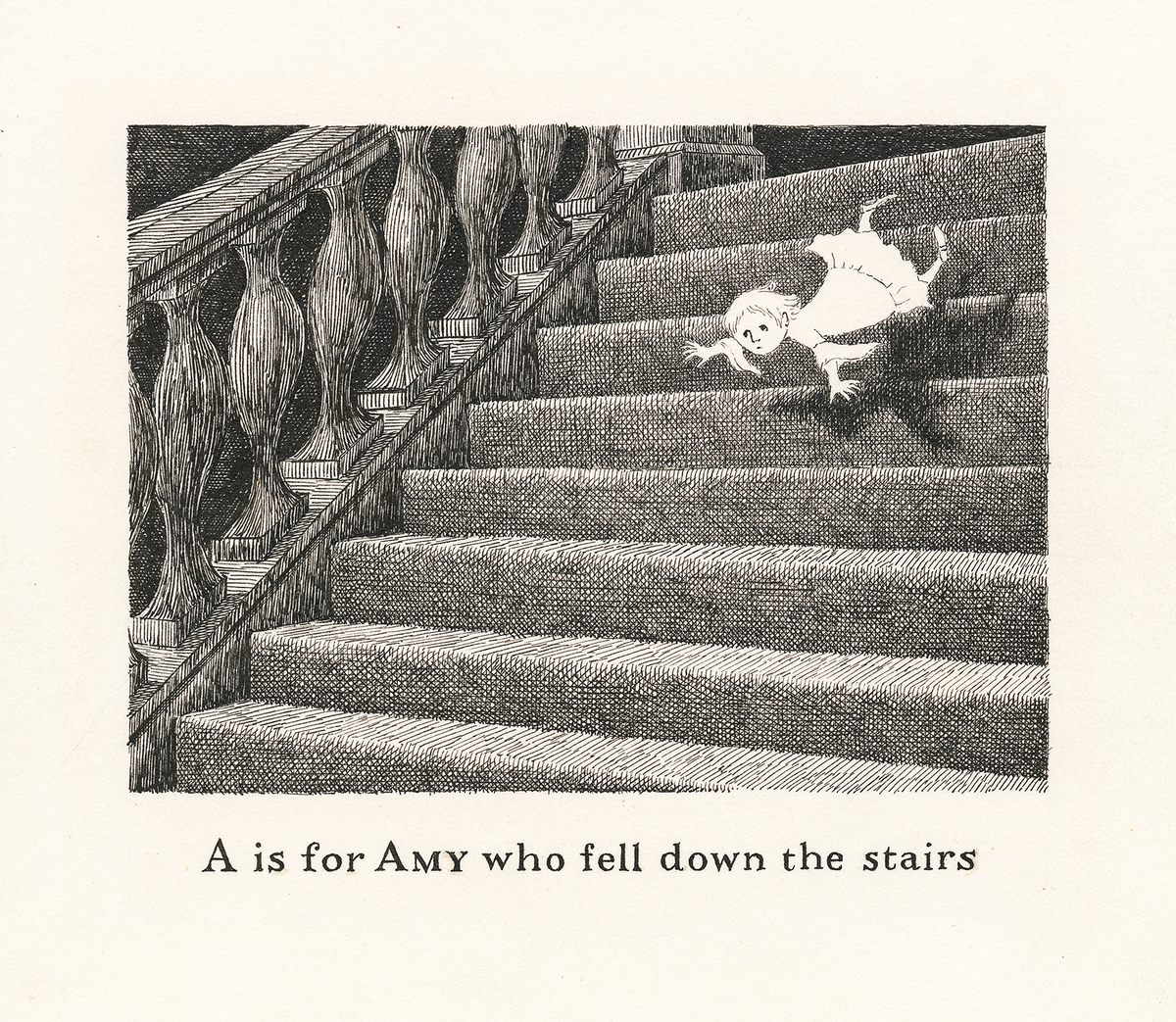

But it remains, recognizably, the lair of an eccentric, or at least a place that still steers into that reputation. In the front parlor, a pair of small legs protrude from beneath the patterned carpet. Even visitors who’ve never read The Gashlycrumb Tinies, one of his darkest, most beloved works, in which children meet untimely ends in alphabetical order (“G is for George smothered under a rug/H is for Hector done in by a thug”) grasp that this is unlike any other writer’s home museum.

The surrounding cabinets and display cases are filled with (to be charitable) Gorey’s collections: books, polished rocks, carved decoys, children’s games. He acquired “any tool that looked like it wasn’t usable because he liked the texture of rusting metal,” Hischak said later. “And X-Files action figures in their original packaging.”

With friends, “he’d go to estate sales and yard sales and flea markets and come back with boxes of stuff he’d place on top of the boxes he’d bought the week before,” Hischak said. “He arranged the house for his own delight, a sort of Wunderkammer.”

The home of a borderline hoarder wouldn’t necessarily make the most reverential museum experience, so much of his stuff has since been distributed. Gorey bequeathed his valuable art holdings— Balthus, Edvard Munch, and Edward Lear, among others—to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, acquired some letters and manuscripts, and San Diego State University took most of the books. The Trust moved thousands of drawings and manuscripts into storage in Manhattan, where it’s based.

The house feels pleasantly cluttered anyway. After a guide explained that friends and a foundation bought the house after his death and established this museum, visitors were free to roam.

There is Dracula memorabilia, and one of Gorey’s famous fur coats although, as a lifelong animal lover, he later rued having worn fur. Museumgoers can linger over cases of original drawings, while a video of Gorey’s opening for Mystery plays continuously in a back room.

Or visitors can do what we did, especially with children in tow, and go on a Gashlycrumb Tinies scavenger hunt. There’s a modest prize for locating all 26 deceased kids.

It’s easy enough to spot George underfoot, or “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs,” because look! there’s a toppled doll on the staircase. But good luck with “N is for Neville who died of ennui.”

We adults were content to tick off about half the Tinies, but my granddaughter insisted we push on. Hint: We found “E is for Ernest who choked on a peach” in the kitchen.

The kitchen, it happens, is where I had chatted amiably with Gorey for a couple of hours 30 years before. He had little interest in parsing or analyzing his singular career. “The longer I go on, the more it all sort of evades me,” he said with a shrug.

Bearded and sneakered as usual, he wore a tattered sweater and a crystal frog—he had a thing about frogs—on a cord around his neck, plus assorted rings and earrings. He served tea and cranberry muffins and mildly admonished those seven cats—“Oh, Billy dear!”—if they dug their claws into his shoulder or made for the muffins.

I mentioned that part to my granddaughter: He seemed incapable of anger toward his cats, even when they knocked over an ink bottle and ruined a day’s painstaking work.

She was excited to glimpse, up a staircase labeled “Wildlife Viewing Area,” a black cat walking about behind a clear plastic barrier. Hischak and his wife live on the museum’s second floor with Embley and Yewbert, named for the characters in The Epiplectic Bicycle and these days the only cats in residence.

It took an hour, but at last we located all 26 Tinies and my granddaughter was delighted with her prize, a bookmark from the gift shop. That marked another change: Gorey was famously diffident about marketing and merchandising. Though he would have appreciated the income, the prospect of lawyers and contracts made him groan.

Today, fans can buy Gorey books, but also calendars, puzzles, mugs, T-shirts, Doubtful Guest iPhone cases, and much more, courtesy of the efforts of the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust.

If Gorey’s legacy endures, the Trust will be the major catalyst. As his will directs, it donates to animal-related charities; Tufts University and the Gorey House also got grants last year. It operates an Instagram account with more than 30,000 followers, publishes a newsletter, and has undertaken an oral history project.

The Trust puts its primary efforts into preserving and organizing the thousands of notebooks, manuscripts, drawings, and personal papers Gorey left behind. In climate-controlled rooms in the Townsend Building on lower Broadway, archivist Will Baker is cataloguing and digitizing the holdings.

“You find yourself laughing out loud, often,” said Baker, who might have one of the world’s better jobs. A new book or anthology might be possible in 2025, he said, to mark Gorey’s centennial. Publishers are interested; the Trust has retained a literary agent.

“My inbox is brimming with inquiries” from would-be licensees, said Eric Sherman, co-trustee of the Trust. He nixed a proposal for Gorey-themed underwear (“an easy no”) but has agreed to a movie adaptation of The Doubtful Guest, and a television series based on Neglected Murderesses.

“It’s a funny thing. When you meet someone and mention Edward Gorey, you either get a quizzical look and ‘I’ve never heard of him’ or ‘I love Edward Gorey.’ My job is to increase the latter,” Sherman said. “You never hear anybody say, ‘I know him, but eh.’”

But the place to actually channel Gorey’s presence—his Kalahari-dry humor, his childlike pleasure in objects and stories, his dedication to his art, his eccentricities—is in Yarmouth Port.

Driving away after the visit, I asked my granddaughter what she would remember: “I liked that he was never mean to his cats,” she said.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook