Why a Small Town in Washington State Is Still Printing Wooden Money

In Tenino, a Depression-era tradition lives on.

Throughout 1931, like most everywhere else, the small U.S. town of Tenino, Washington, found itself in the throes of the Great Depression. But it was an especially grim day in December of that year when the Citizens Bank of Tenino closed its doors after running completely out of money.

Nationwide, the bank was just one of over 1,000 that closed in the fourth quarter of that year. But for tiny Tenino, which only had one bank to begin with, the situation was especially dire.

To address the cash crisis, the then-publisher of the Thurston County Independent newspaper, Don Major, went to the city council with an idea: issue the townspeople a temporary scrip in order to facilitate transactions inside the community.

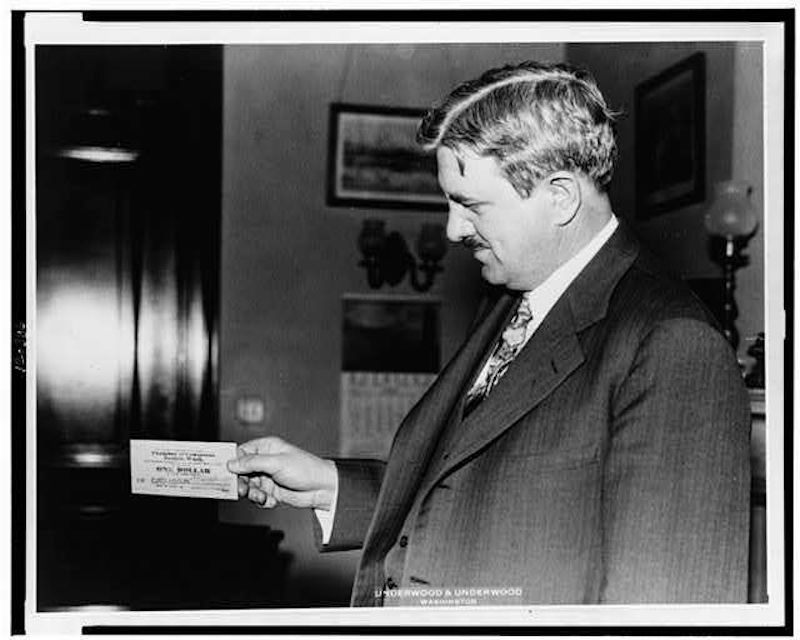

A lot of cities and towns across the U.S. ended up employing a similar concept, printing scrip notes or IOUs on slips of paper. But by the end of December, Major had devised a way to turn Tenino’s monetary misfortune into a highly successful publicity stunt.

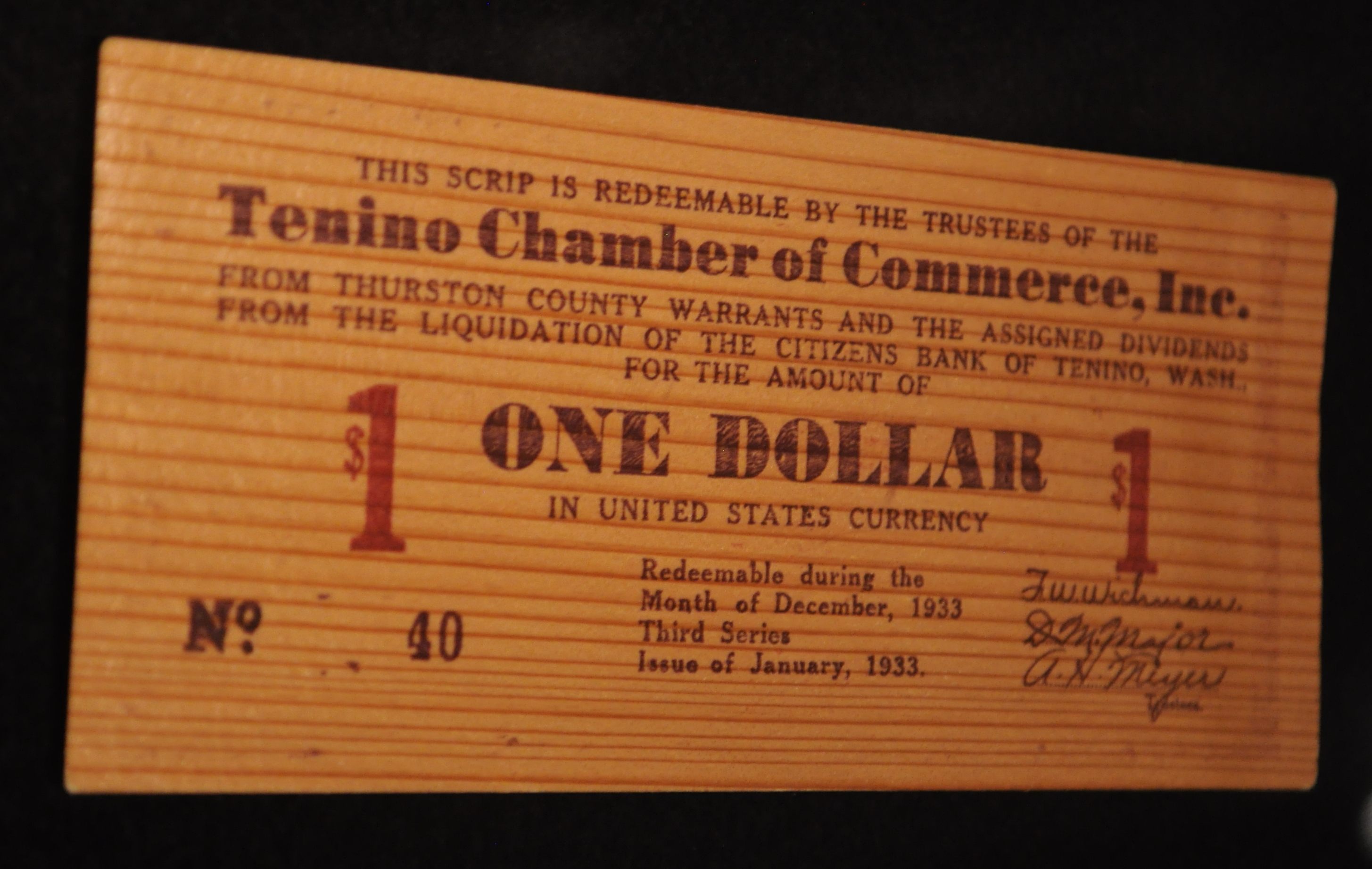

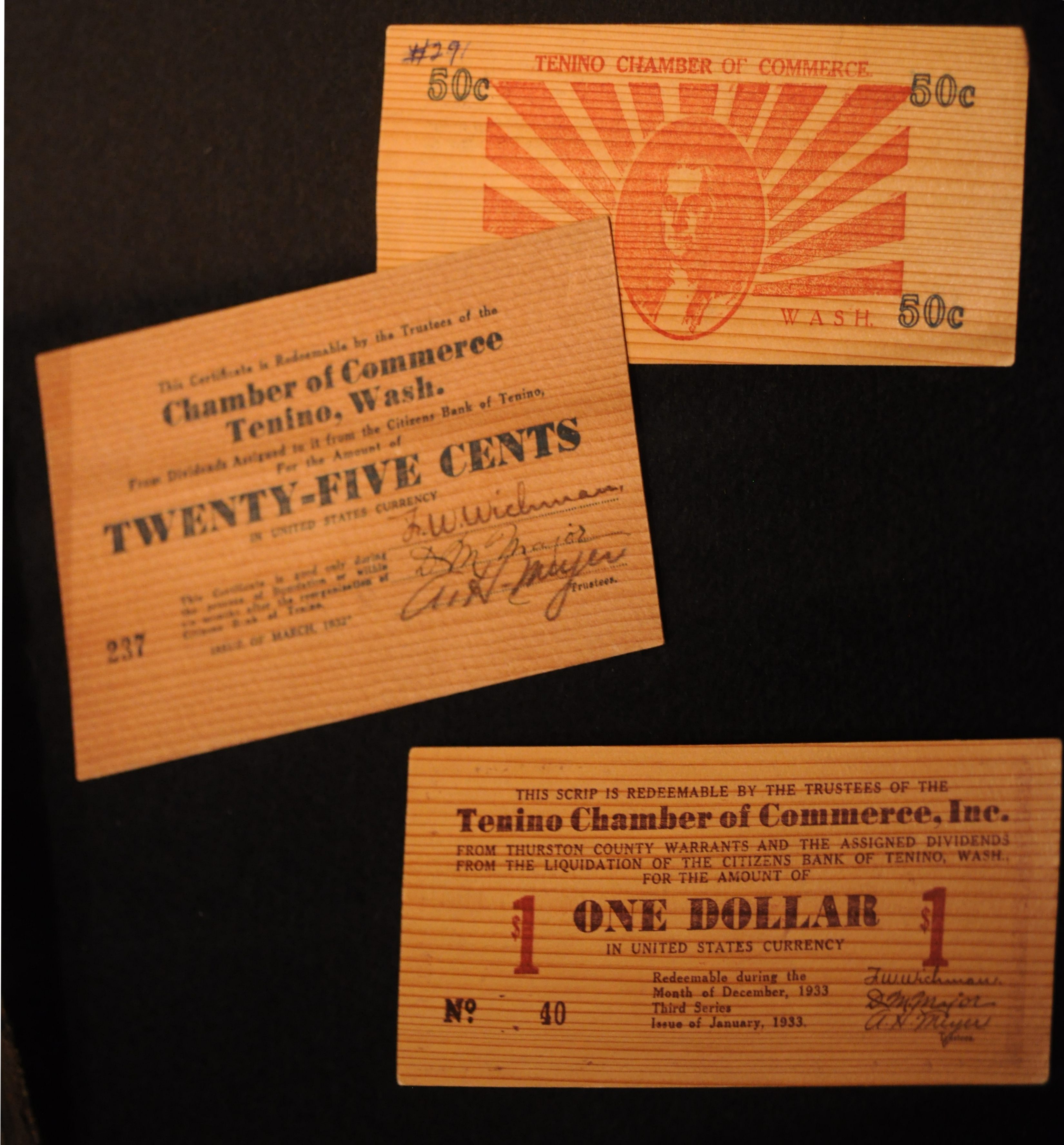

Major began printing pieces of temporary currency on thin, 1/80th-of-an-inch-thick pieces of “slicewood,” which amounted to two strips of spruce, laminated, with a piece of paper in the middle. He’d previously used the material to create novelty Christmas cards. He started with 25¢ denominations, and later produced somewhat larger amounts, including 50¢ and $1.

Word of the wooden money spread quickly, and soon requests from currency collectors across the country poured in. Over the next several years, the Tenino Chamber of Commerce would issue over $10,000 worth of wooden money from their mechanical Chandler Price printing press. As the story goes, only $40 of it ever ended up being spent back in Tenino.

“In a sense it backfired, and in a sense it worked out even better than they expected,” says Loren Ackerman, who today is one of only two people who still prints commemorative wooden money in Tenino, on what he says is the very same press. “They were able to sell all this wooden money, but very few of them came back to be redeemed.”

Ackerman says that the Tenino Depot Museum, which now houses the original press, holds a number of “request letters” from people who would write to Tenino to see if they could get their hands on the unique currency. “In one of the letters it says, ‘I’ll send you two of my Washington bicentennial tokens if you send me one of your wooden flats,’” says Ackerman.

Even after the Depression had finally abated, Tenino’s tradition of wooden money survived. The town continued to print souvenir and commemorative bills, usually annually, to meet the demands of collectors.

Chris Hallett, who moved his Edward Jones financial advising practice into Tenino’s old bank building in 2002, sees the brittle bills as an important part of the town’s history. “What really got me about the wooden money was how unique it was to Tenino. It’s a very unique situation in a very small community,” says Hallett. The walls of his office are adorned with pieces of wooden money that he’s personally collected, some dating back to the original fervor of the 1930s, while others are more recent. He even had a special commemorative bill made to celebrate the opening of his business. “I really got into it when I realized that my office is in the building that was the bank that created this. I’m living the history working there,” he says.

But the wooden bills of Tenino are more than just history. Ackerman has been running the original printing press since the 1990s, when he took it over from the previous caretakers after they grew too old to operate it safely. “Running the press is… how should I put it… not OSHA-approved,” he says. “If you slip at all, you’re going to bite your fingers.” Other than some deterioration of the rollers, which Ackerman had to replace around 2013 after the machine began putting out substandard wooden money (“I look back on it and it was disgusting. I should have thrown it all away. It was horrible.”), the original press is still in operation. It now gets fired up at least once a year to make souvenirs for the city’s annual Oregon Trail Days celebration. Ackerman has also taught one of his sons to use the press so that the tradition can continue when the time comes.

Recent printings of wooden money can be purchased at local businesses such as Scotty B’s Cafe, and either kept as a souvenir, or spent in town. According to Ackerman, around 15 town businesses will accept the novelty money, although most people prefer to hang on to the bills rather than spend them.

Ackerman says he’s happy to see the wooden money leave the city and spread the history of Tenino, but as a collector, Hallett says he likes having them around locally too. “I like to bring these artifacts back to Tenino so they can be shared with the community,” says Hallett. Both men, however, are happy that the story of Tenino’s wooden bills reaches far outside of their little city. “I didn’t understand what all that press meant to people all over the world. That’s what’s amazing to me,” says Ackerman.

Just don’t bring up wooden nickels. “Everybody thinks that the wooden nickel came from Tenino. That’s the biggest fallacy out there. It’s bills. It’s actual currency,” says Ackerman.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook