How the Chernobyl Disaster Sold Europe on Washington Wines

Nuclear tragedy created opportunity a world away.

Catastrophe swept over the small city of Pripyat, in Northern Ukraine, in April of 1986. At the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, a botched safety test resulted in an earth-shaking steam explosion at Reactor 4—the facility, with its bio-hazardous contents, was violently cracked open.

Soon after the accident, gigantic plumes of fission products were expelled into the atmosphere. Dozens of townspeople began to taste something metallic in their mouths, and people got headaches; eventually there were uncontrollable fits of vomiting. More than 24 hours after the initial blast, the town was evacuated due to radiation concerns. Underneath a strange cloud, lively Pripyat withered.

Likewise, the hearts of people across Europe sank as it became clear that radioactive particles were being carried westward by the winds. Indeed, as far as Sweden, radiation levels set off alarms at the Forsmark Nuclear Power Plant. The exact impact of the fallout on crops was unknown.

As the effects rippled across the world, it disrupted the wine world too. Scandinavians, wary of the situation, began to forego purchasing wine from France and looked for an “uncontaminated” substitute. Soon enough, a nuclear disaster in Eastern Europe had the unexpected consequence of helping American wines from Washington find their way onto the international market.

“Concern about Old World wines that might have been tainted by atomic pollution,” says Mike Veseth, editor of The Wine Economist, “drove buyers in Sweden to look for Bordeaux-style wines from the New World.”

The first person to take advantage of this opening had not actually worked in wine for very long. At the time, Tom Hedges had recently been canned from his job as CEO of a Canadian produce company. “I was just sitting there looking around, slightly depressed, and I remember hearing about Chernobyl, but I didn’t frankly give a damn at that time,” says Hedges, who was the father of two young children. “I was looking for work.”

He found himself entering a new industry through a friend of a friend: spirits. “We loaded up and drove from New Brunswick, Canada, to Tri-Cities, Washington,” he says. In the Evergreen State, Hedges sold wines to companies in Taiwan. Soon, the blossoming wine seller was shipping West Coast wine to a supermarket in Tahiti.

With these business dealings, Hedges was entering virgin territory. Although wines from Washington State were beginning to earn acclaim, most commercial-scale wineries dated back less than 20 years, a blink by wine standards. The industry was still developing an international reputation, and across the world, French wines dominated the market.

Still, Hedges was successful enough at selling Washington wine in Tahiti to ruffle French feathers. Despite the fact that Hedges didn’t actually own a winery, he acted as a sort of middleman—a négociant, as they’re called in the wine industry—and began buying surplus wine from Washington sources to sell to someone he’d met: a Swedish distributor of alcoholic beverages.

“Mind you, we have no money, no winery, no vineyards,” says Hedges. But the Swedish distributor accepted his samples, and Hedges and his French-born wife, Anne-Marie, began to toy with potential names for their new wine label. “Issaquah Ridge” and “Columbia Valley Vineyards” were the main contenders, with a version of the latter being shipped to Scandinavia initially. It was only through the advice of a friend and wine bottler, who said they couldn’t defend those other names, that the modest couple began to consider naming the brand after themselves. Thus, Hedges Columbia Valley Cabernet-Merlot was born.

For the first year, the Hedges shipped bulk wine that they had blended and bottled in recycled containers. Considering the radioactive circumstances, Swedish customers, across hundreds of liquor outlets, were willing to try the foreign wine. They liked it.

“Our brand took off with A++ rating from a wine journalist, Mats Hanzon, whom I later met, and we took on as partner in 1989,” says Hedges with a laugh. “Still with us today.”

With some quick thinking, a few good connections, and lots of elbow grease, the Hedges were able to tap into heightened demand for uncontaminated spirits. After just three years, Hedges says, the sales quadrupled to about 200,000 litres per year. Other Washington State wines also found a footing in the global market, as international visibility for the region’s product swelled.

“Tom Hedges answered the call and created Hedges Cellars wines specifically for the Swedish market,” says Veseth, the Wine Economist, of Hedges’s post-Chernobyl business. “The wines were an instant success, opening the door for more Hedges wines and more Washington State wines in the Old World.”

Among Washington wineries, Hedges singles out L’Ecole N° 41 as a maker and exporter of great wine, and the state’s largest winery, Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, a significant international exporter. Each Washington label has, over the years, continuously helped reinforce the worldwide reputation of the West Coast’s non-Californian wines.

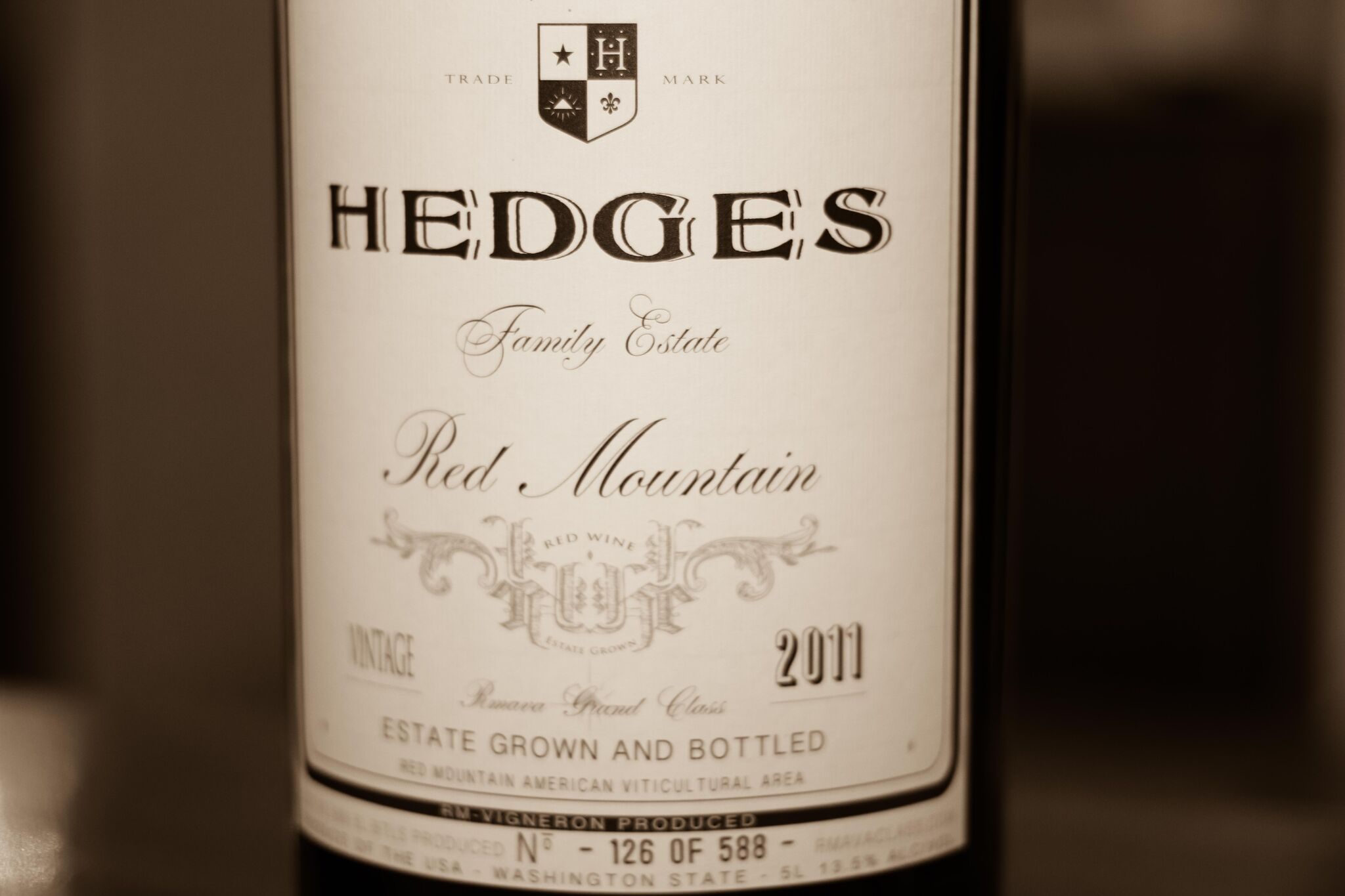

Eventually, success allowed Hedges to create his own winery. More than 30 years since the nuclear plant disaster, Hedges Family Estate Wine is now a 130-acre vineyard, in the heart of Red Mountain, where their family chateau is laden with wisteria bushes and green pastures. On a summer day, Hedges recounts how a catastrophe on the other side of the world changed his family’s destiny.

“Within about six months we were famous in Sweden—all thanks to Chernobyl,” says Hedges, with a long sigh. “Funny how life works.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook