In Belarus, the Ancient Tradition of Healing Whispers Slowly Disappears

A centuries-old practice with little place in the modern world.

Babka Vanda—eyes like shiny buttons, hair tucked beneath a headscarf, dressed in a floral-print blouse—told photographer Siarhiej Leskiec a story about her grandmother. She was thought to be a witch, Babka Vanda said, and the local priest had forbidden her from treating people—until, that is, he was bitten by an adder. She whispered words into the wind, and he was cured. She eventually passed that power, to heal through whispers, to Babka Vanda.

Today, this ancient Belarusian healing tradition is slowly disappearing. For Leskiec, it’s a part of his country’s heritage, and he wants to document it before it is gone completely.

Like other former Soviet republics, independent Belarus has evolved in ways both predictable and unexpected. Geographically, it’s small and landlocked between the Baltics, Ukraine, Poland, and Russia. The country remained majority Orthodox Christian through the years of Soviet-enforced atheism. Politically, it precariously straddles the divide between the Kremlin and the West, and its leader, Aleksandr G. Lukashenko, has been in power for 23 years, and is seen as more dictator than politician. Through all of this, the healing tradition practiced by women such as Babka (Belarusian for “grandmother”) Vanda has remained strong—until now. It is unlikely to survive the decline of the country’s rural population. Today, three of every four Belarusians live in cities.

“The tradition is preserved for 1,000 years of Christianity, Stalinist repression, and atheism and persecution of believers in the USSR, but is dying now under the influence of globalization and urbanization,” says Leskiec. “Young people do not believe in these ‘tales’ and do not want to learn. They think it is unnecessary and primitive.”

The whispering healing is heavily ritualized. “For each disease there are special words. These are small, often rhymed text that you want to say in one breath and a barely audible whisper,” says the photographer. “Most often [they] read words about the patient, or over the water, then this water [the] patient must drink and wash her face and sore place for three days.” Whispering occurs on certain days for men and other days for women, and never on Sundays or holidays. The healers treat diseases and infections, but also more spiritual concerns: “The strongest whisperers can even cast out evil spirits.” Their methods can also incorporate herbs and other rituals.

The healing tradition is believed, according to Leskiec, to have its roots in paganism. When Christianity came to Belarus, the spells were adapted to incorporate elements of organized religion, including the names of saints. Christian orders were highly suspicious of the spells—“damned pagan whisperers,” they called them, according to Leskiec. However, religion and folk practice found a way to coexist. “Now even the whisperers themselves are deeply religious Christians, but they have their own understanding of faith and tradition.”

One image from the photographer’s documentation project depicts a “female cross,” a traditional crucifix that has been draped in pieces of cloth. The cloths are donated each year, by the villagers, to ward off evil and maintain good health. Says Leskiec, “So the cross is adorned as a woman in a traditional costume and the symbol of Christianity is like a female goddess.”

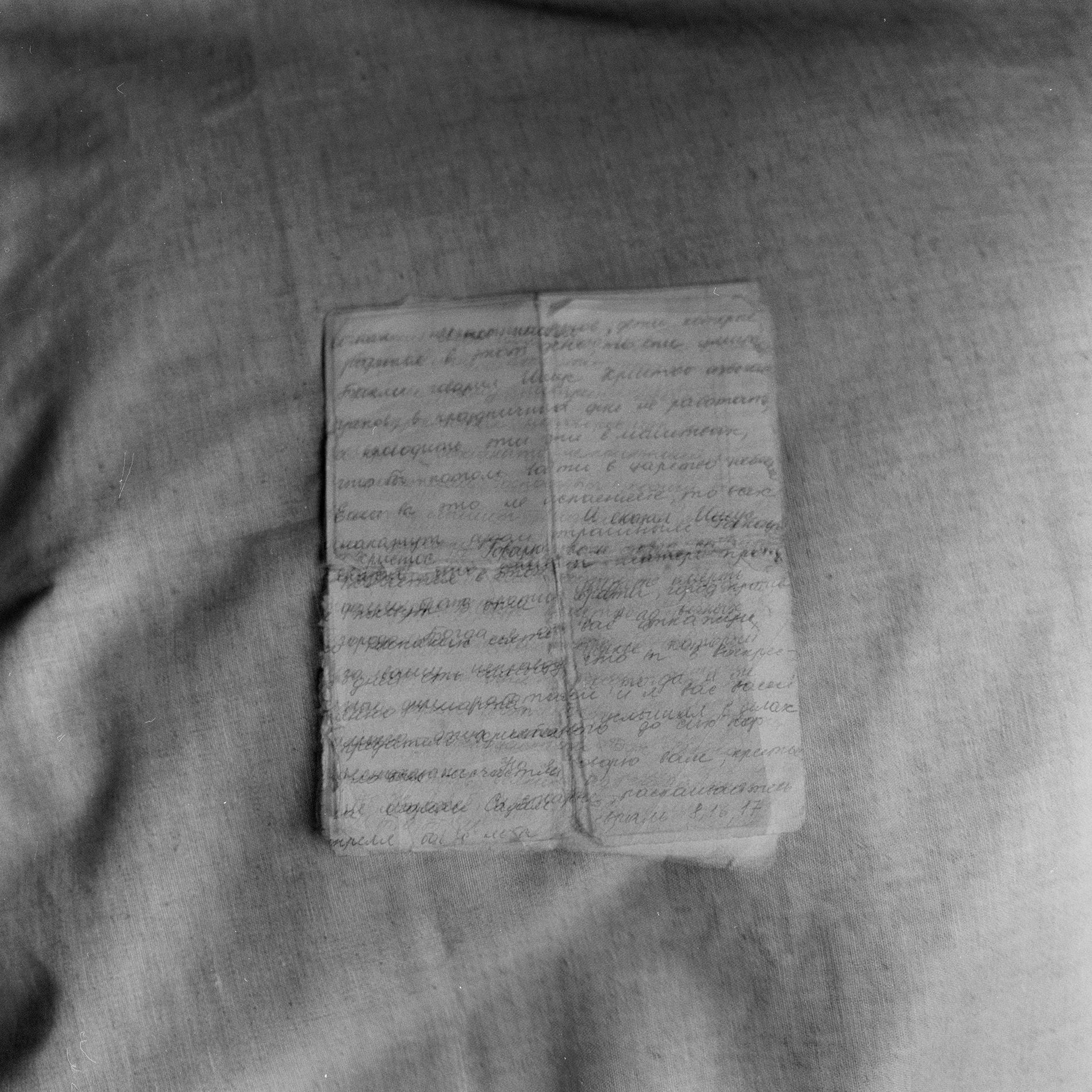

It has always been difficult to become a whisper healer. Knowledge is passed to children—male or female—between seven and 12 years old, by close relatives, usually grandparents. “All prayers were taught verbally and rarely were they were written down on paper,” says Leskiec. The were other requirements for the profession as well. “A person should be kind and curious, purposeful, and open to communication with others.” But initiates must then wait, sometimes for decades, before they can actually engage in the practice—after they’ve built their own families or gone through menopause.

Leskiec’s project began in 2012, but it took time, not just to find the healers, but to gain their trust. He spent several years learning about the tradition before being, in a way, initiated. “After that it was easy for me to talk to other whisperers,” he recalls. “Our knowledge was equal.” At the start, Leskiec found 40 healers; today he knows only five. His goal is to create a book from the project so the stories can live on. Every year, he says, there are fewer inhabitants in rural villages, and fewer young people to teach. “Old people live there,” he says, “and together with them, old healing traditions of ancient Europe also die.”

Atlas Obscura has a selection of images from Leskiec’s project.

![Babka Nadzeja. "When people ask for help, I can not refuse them. The only thing that I can not help [is] my family .... Whispers only help strangers."](https://img.atlasobscura.com/FHf48q0ChJZHANcqBBEjl3TCxdWZiOtJTPkuT-SN8lg/rt:fill/w:1200/el:1/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9hMGU5OTFhMTYz/YmUxOTMyY2RfTEVT/XzAwOS5qcGc.jpg)

![Babka Stassia, who helped a family from Minsk with a crying, sleepless child. "As I start to whisper he softly and sweetly [falls] asleep. Parents didn’t cease to be surprised [by the] a strong force in a whisper. This is the power of God!"](https://img.atlasobscura.com/VcsqV4O0aHFHAxBgqzTEIlM3g0-uVygEBwrxpLqdmy4/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9hMGU5OTFhMTYz/YmUxOTMyY2RfTEVT/XzAwNC5qcGc.jpg)

![Babka Alena. "I was the youngest child in our family .... I long did not want to treat people, was ashamed, was afraid [...] The times were such that the people were even afraid to go in the church."](https://img.atlasobscura.com/rz_26KU8ShCUjLEb_rptjf3T97CfUA9V5msny2fOpl4/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9hMGU5OTFhMTYz/YmUxOTMyY2RfTEVT/XzAwNy5qcGc.jpg)

![Babka Maria. "Older people who know the words [are] already dying and young people don’t want to learn, they don’t believe in it. But the evil in the world does not become less .... Old people and children come every day to me, but I don’t know who will whisper after my death."](https://img.atlasobscura.com/SsHPMWRnPWLnN4OFEfo1SruQv3tR5J98JRNNSa6PYQ0/rs:fill:12000:12000/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy9hMGU5OTFhMTYz/YmUxOTMyY2RfTEVT/XzAyMS5qcGc.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook