How Gremlins Went From Fairy Stories to Warplanes to Hollywood Legend

Meet these slippery, mischievous reflections of our anxieties about technology.

It was 1944, and an Allied pilot was flying a B-17 bomber over Nazi territory. Suddenly, the plane began to rattle. He checked his instruments—they were going haywire. As the rattling and noises continued, he glanced out the cockpit window and saw something: a creature, about three feet tall, gray and hairless. Its teeth were sharp and its eyes were red.

The pilot soon spied something else, an owl-like creature hammering at the airplane’s nose and dancing a gleeful little jig. The crew started some “fancy flying,” and managed to shake the creature or creatures off.

This story was related in The World of Lore, by Aaron Mahnke, host of the popular Lore podcast. Although the pilot survived this frightening incident, the story goes, he remembered it his entire life. He believed he had encountered the mythical gremlin, and he was far from alone.

Today the impish creatures known as gremlins are best known from Joe Dante’s 1984 horror hit Gremlins and its 1990 sequel. Though their origin begins in the deep reaches of Western mythology, they really distinguished themselves during the first half of the 20th century, when they came to represent everything that could and would go wrong with modern technology.

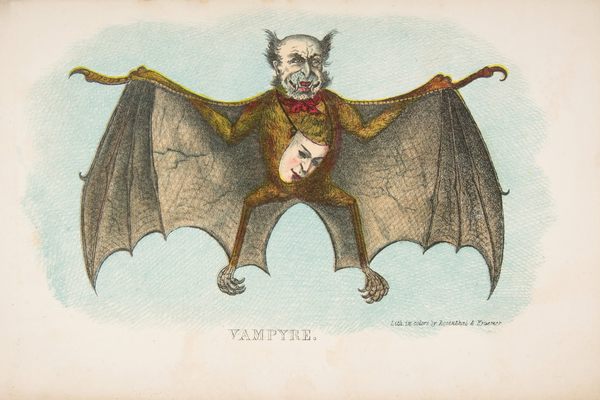

“Gremlins are part of the little people folklore,” says author and folklorist Peter J. Dendle of Penn State Mont Alto. “When a door is open when it should be closed, or you’re missing something that should have been there that you know you placed there, that would’ve been imparted to little people.”

According to Emily Zarka, host of Monstrum on the PBS Storied Channel, and a professor at Arizona State University, these little people, or “fae folk,” were complicated creatures that often evolved with the times and weren’t always bad. “Fairy folk were dangerous, but might help you out, usually with a price,” she says. “In Britain, by the 16th century, fairy lore was everywhere, arguably coming from more of the elf tradition.”

Elves, imps, fairies, whatever form these mischievous characters took, they were long used to explain away the unexplainable and the unfortunate, and were firmly cemented in the cultural dialogue of Western Europe by the early 20th century. Unsurprisingly, with the advent of new technology, the traditional mayhem makers followed us wherever we went. And at that time, we took to the skies.

As aviators navigated new, uncertain technology and an unfamiliar environment, lots of things could and would go wrong. It was perhaps comforting to have a mystical scapegoat take the blame for the myriad disasters that could befall a pilot, especially during wartime.

“The first military airplane was invented in 1909,” Zarka says. “Flying is a really complex process, let alone under the stress of war.… I think that in a lot of ways it might’ve been easier, not even just to explain away the mechanics, but to explain away human error. It would be hard to take responsibility for the death of another pilot in your group.”

The first rumblings of what we now know as the gremlin came from members of the British Royal Air Force (RAF) during World War I. According to the British magazine The Spectator, in 1917 British forces … “detected the existence of a horde of mysterious and malicious spirits whose purpose in life was … to bring about as many as possible of the inexplicable mishaps which … trouble an airman’s life.”

According to prominent aviation historian Robert O. Harder’s MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History article Gremlins: A Pilots Worst Nightmare, one of the first documented sightings of a gremlin came from a British pilot who crashed into the sea in 1923. Though reports vary, in one version he claimed that a diminutive band of monsters had jumped out of a beer bottle, created mayhem in the cockpit, and tampered with the engine, causing him to crash.

“They would cause chaos for pilots, everything from moving stuff around, draining batteries, stopping guns from working, or landing gear from deploying, they might mess around with compasses, that kind of a thing,” Zarka says. “They were rarely ever singular. They usually were in groups.”

By the late 1920s the term “gremlin” had entered the popular lexicon. According to Harder, some believe the name is derived from the old English word greme (“to vex”) mashed with “goblin.” Others speculate the name was coined by RAF members who combined the Brothers Grimm of fairytale lore with the name of a popular beer, Fremlin’s. The prominence of beer in the story might also carry some explanatory power.

As aviation technology became more advanced—and thus harder to understand and completely control—superstitions around gremlins grew stronger. By the time of World War II, aviators had an all-new, complex language and mythology. That’s when the petrol-chugging gremlin truly became a phenomenon.

American aviators began to evoke the gremlin, as did journalists. “There I was directly over the Abbeville airfield, the place filthy with Me-109s,” one World War II bomber pilot exclaimed, Harder writes, “when one of those bloody Hun gremlins jammed the camera toggle!”

No one seemed to agree exactly what gremlins looked like—only that they were little and annoying. “They stand about a foot high when in a fully materialized condition and are usually clad in green breeches and red jackets, ornamented with neat ruffles,” The Spectator reported in the 1940s. “They always wear spats and top-hats, although the Fleet Air Arm report a marine species with web-feet and fins on their heels.”

While gremlins were often destructive, they could be helpful if they liked you, much like their fae folk ancestors. According to Hubert Griffith’s 1942 Royal Air Force Journal article The Gremlin Question, if a pilot was suffering from low visibility, a gremlin might appear on the aviator’s shoulder with advice: “You silly fathead—you’re upside down.”

Whether the gremlin was actually thought to be a creature, or simply a shorthand term for things going inexplicably wrong, the myth grew to be a marketing tool for the British wartime propaganda machine. Posters cautioned servicemen and women of all branches to avoid “gremlins” by checking their equipment, operating their planes and machinery responsibly, and staying on high alert.

Gremlins think it’s FUN to HURT you—Use CARE always.

Gremlins will PUSH you ‘round—Look where you’re going.

Gremlins LOVE to pitch things at your eyes—WEAR SAFETY GOGGLES.

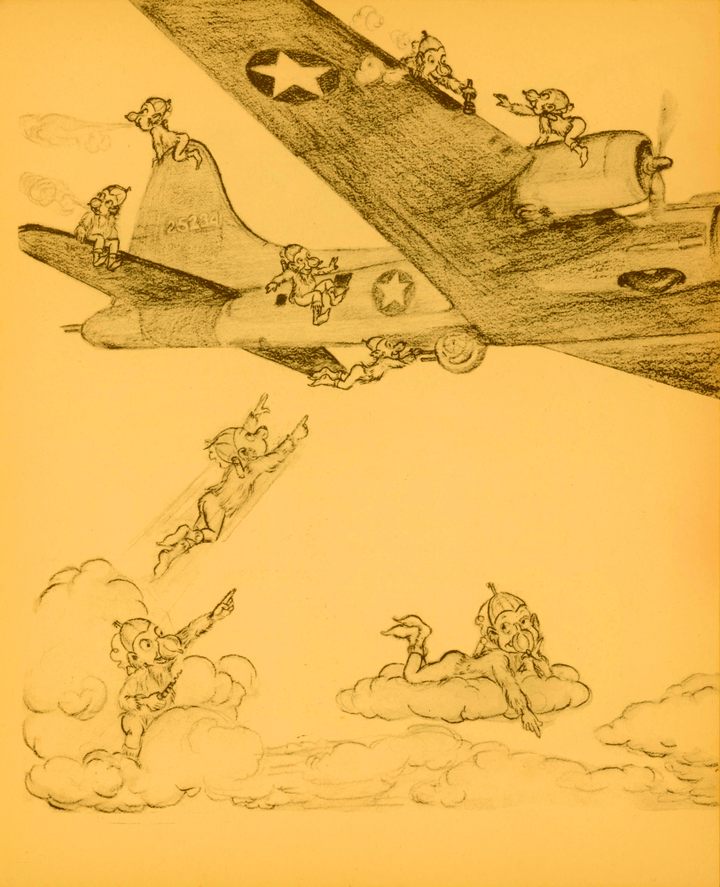

Serious papers were written about the gremlin phenomenon and poems expounded on the numerous breeds in the gremlin family. In 1943, Bugs Bunny battled gremlins attempting to wreck a military aircraft in the short “Falling Hare.” A famed B-17 was named “Red Gremlin.” According to Harder, the American Women’s Airforce Service Pilots adopted a lady gremlin named “Fifinella” as its mascot. “Baby female Fifinellas were ‘Flippertygibbetts,’” Harder writes, “baby males were ‘Widgets.’”

One young RAF lieutenant was captivated by tales he heard from fellow flyers about this mysterious monster. “Maybe you don’t know what [gremlins] are,” Roald Dahl wrote to his mother in June 1942, “but everyone in the RAF does.… It’s really a sort of fairy story … ”

This inspired the burgeoning storyteller to write The Gremlins, the story of six-inch creatures who created mayhem on RAF planes during the Battle of Britain, in retaliation for the destruction of their home to make way for an aircraft factory. Playing on the duality of gremlins, they eventually begin to help the pilots after they are bribed with used postage stamps and promises that their forest home would be restored.

This environmental fable further connected gremlins with the fae tradition, as fairies and other “little people” often tormented humans who had harmed their homes.

According to The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington by Jennet Conant, Walt Disney was enchanted by advance word of Dahl’s story and had wished to make it into a cartoon. Dahl was invited to Los Angeles, where he passed himself off as a “gremlinologist” and described the little men in great detail. “I really do know what they look like having seen a great number of them in my time,” he said.

In 1943, Disney and Random House printed 5,000 copies of Dahl’s The Gremlins: A Royal Air Force Story, with illustrations by Disney animator Bill Justice. The book was a hit, with admirers including Eleanor Roosevelt, but the movie idea was shelved, since the RAF demanded final approval.

After the stress of World War II was over, sightings of gremlins fell dramatically, but their place in the pantheon of modern monsters—and the fear of the unknown in our own technology that they represented—was secure. They would pop up occasionally, particularly in the famed 1963 The Twilight Zone episode “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” written by famed horror author Richard Matheson, in which William Shatner spies a nasty specimen on a commercial plane’s wing. He reaches heights of hysteria that only he can to try to convince others that their lives are at risk.

In 1984, gremlins came back down to earth. They were no longer aviation goblins, but still had a connection to their forebears, as they wreaked havoc on modern technology in a small town in the Steven Spielberg–produced Gremlins. “We know Spielberg has actually acknowledged that Roald Dahl’s story influenced the Gremlins film,” Zarka says.

It was the perfect time for a comeback. Technology was rapidly advancing, and human lives became ever more intertwined with machines. The movie uses the gremlin myth, like Dahl’s environmentalist fable, to shine a light on humans’ disrespect for tradition and other cultures (“Don’t ever feed him after midnight!”) and the mayhem that can result from this arrogance.

Zarka feels gremlins are in the same class as many recent mythical creations, inspired by a combination of traditional mystery and distinctly modern anxieties. “I think if we’re looking at gremlins, we’re looking at things like the chupacabra, Slenderman. Like many monsters throughout history, part of it is about this new technology that emerges that we’re not sure exactly how it fits into our lives,” she says. “There’s also definitely a nostalgic element to a lot of modern monsters, as well. As our world becomes more and more technologically and scientifically advanced, I think that a lot of people like to hold on to the idea that there are still some mysteries out there in the world.

And although no one seems to spot physical gremlins anymore, the metaphorical gremlin is now well-established shorthand for technical and mechanical failures and glitches. Maybe it’s just a matter of time before impish little creatures start heckling us from inside our laptops.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook