Railyards Were Once So Dangerous They Needed Their Own Railway Surgeons

Feet, hands, and lives were at risk.

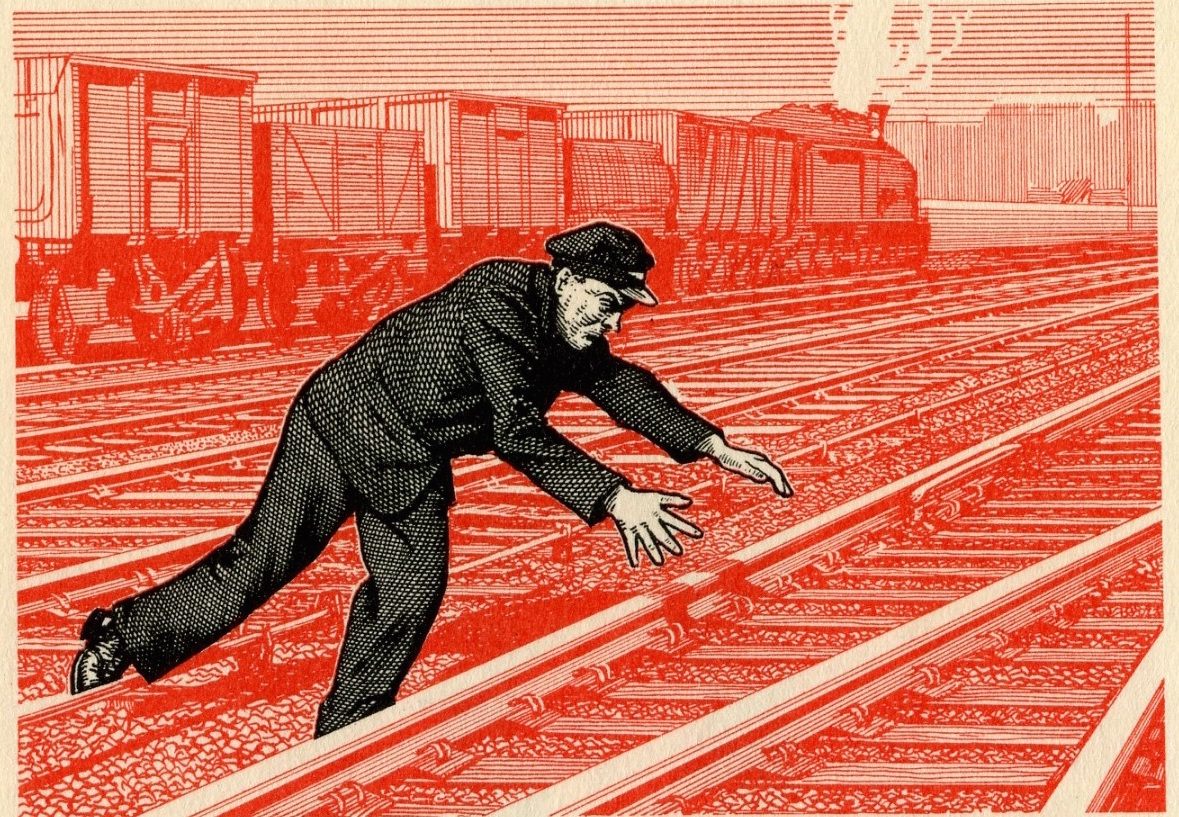

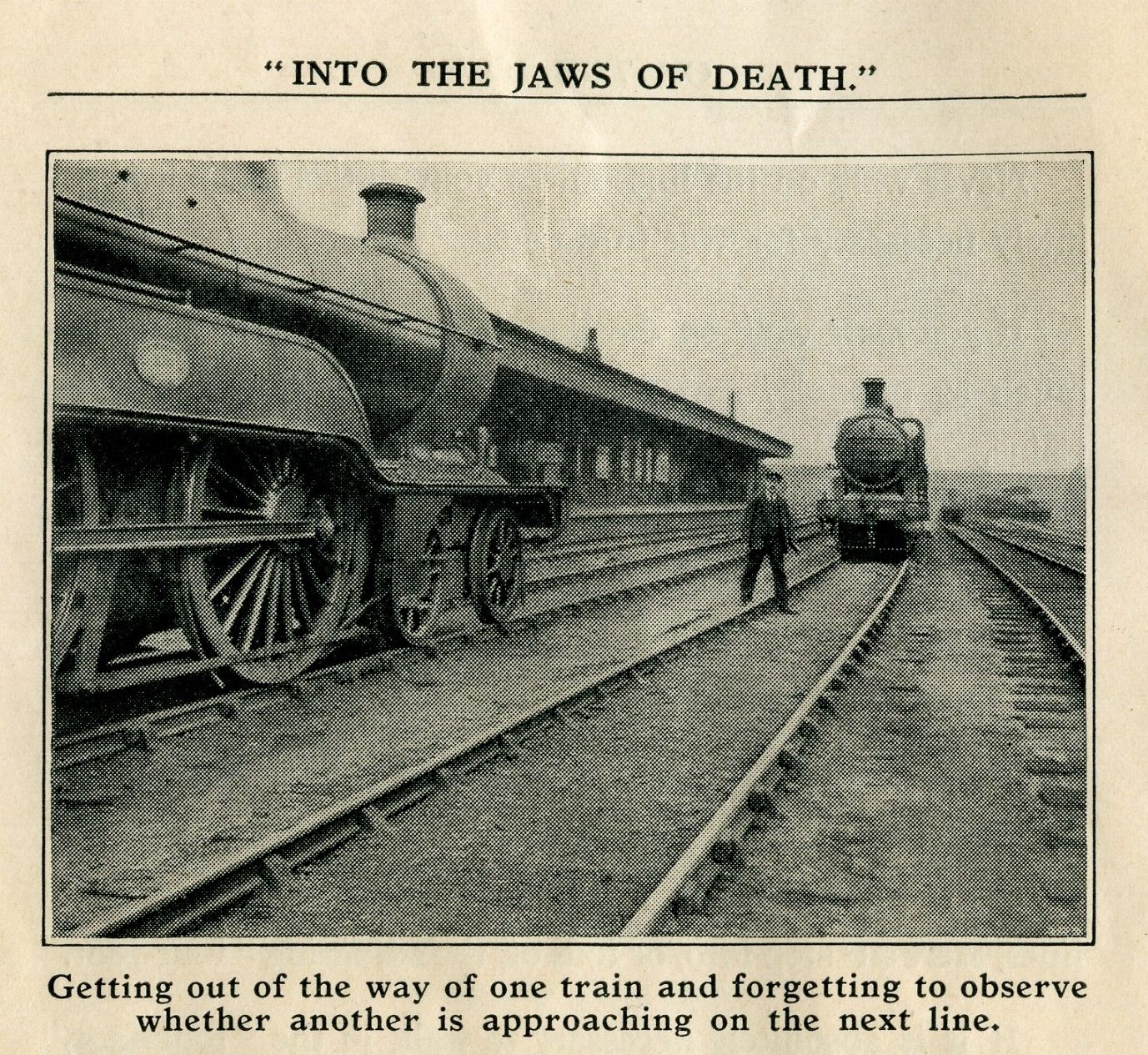

To work for a 19th-century railroad, it helped to be fearless, tireless, and a little reckless. Railway workers spent long shifts maintaining tracks, coupling and decoupling cars with swift and practiced moves, or unloading goods in train yards, and throughout all those exhausting hours one unlucky moment could cost them a hand, or a leg, or more. “They suffer as if they were fighting a war,” said Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, in 1892. In the United States, in 1889, one in every 35 railway workers was injured each year, and in the more dangerous “running trades” that put some of them in close proximity to trains, that rate jumped to one in 12. Fatalities were common, too. One out of every 117 workers died on the job. In Britain, railway accident reports contain more than one incident where the body of a man struck and killed by a train flies through the air to hit and injure a coworker.

Railway work was so dangerous that an entire medical specialty developed to deal with it. In the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, companies hired “railway surgeons” to staff private hospital and health care systems. An on-call doctor could rush to the scene of an accident, or be ready to receive a bleeding, injured worker sent to them by train. They were pioneers in emergency medicine and specialized in amputations and prosthetics. Some consider them the world’s first trauma surgeons.

In the 1800s, it was generally rare for a private company to take such an interest in its employees’ well-being, but railway surgeons were not celebrated figures. Workers resented having their wages garnished to pay the surgeons’ salaries, while other doctors scorned them as lackeys of the railroads. Today, even in a world still full of railroad enthusiasts and obsessives, they have been all but forgotten.

“I’ve been to railway museums all over the country and very seldom do you see anything connected to railway surgeons,” says Robert Gillespie, a pediatric nephrologist and founder of the online Railway Surgery Historical Center.

Even in the railroads’ heyday, the problem of worker injuries went relatively unremarked upon. Dramatic crashes made the papers, but not the daily grind of injuries resulting in disability or death—even as those numbers added up. In Britain, in the years before World War I, for example, for every one passenger casualty, there were nine among workers. “The worker cases, they’re not news. They fade into the background,” says Mike Esbester, a senior lecturer at the University of Portsmouth, whose project, Railway Work, Life and Death, is gathering accident reports in a database. “It’s almost as if there hasn’t been anything to forget, because people haven’t been so aware of it.”

The database shows just how dangerous a railroad career could be. Volunteers from the National Railway Museum in York have been logging handwritten reports created by the Railway Inspectorate from 1911 to 1915, building a database of around 4,000 accidents so far. These inspection reports represent only about three percent of all incidents in those years, and it’s not entirely clear how inspectors chose which cases to document or investigate; they range from fatalities to “someone who pinched their thumb,” Esbester says.

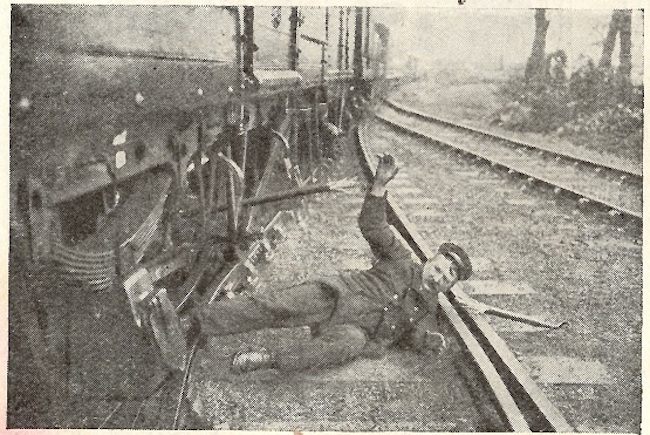

But the reports include vivid accounts. A platelayer was hit by a train twice in three weeks. A carriage cleaner died trying to save a colleague from being hit. A man was crushed between two wagons 18 hours into a 26-hour shift. They also show how some continued to work after serious injuries: a man who needed new artificial kneecaps every four to six months, or a “good driver” of “excellent character” with a wooden peg leg.

“People were being asked to work in dangerous situations,” says Esbester. “The companies, which were profit-oriented, didn’t have the same concept of safety culture as we do now. If workers died or were injured, there was some compensation payable, but my hunch is, there was a trade-off, in the minds of management, between the cost they had to pay out when someone was killed at work and the costs of changing a particular mode of working.” In Britain, the companies encouraged their workers to learn first aid, and sometimes funded local hospitals. But for the most part, they didn’t bear the full cost of the dangerous nature of the work.

In the United States, starting around 1849, railroads began to hire doctors, and took a slice of employees’ wages to help fund their salaries. By the 1890s, there were around 6,000 railway surgeons across the country, 1,500 of whom were members of the National Association of Railway Surgeons. Their patients were often in bad shape, according to accounts that Gillespie dug up—“tied up with rope, old rags, soiled handkerchiefs, or anything else lying about.” By the time the patient arrived, an injured limb might look “like nothing but bloody rubbish,” and the patient would be likely to bleed out. If the doctor could make it to the scene of an accident, he or she might have to work in the woods, on a back porch, or in a hotel room.

Railway surgeons might not have earned the admiration of their peers, but they had a sense of purpose about their work. “We are the selected servants of the great railway companies of the whole continent, honored by them with the special appellation, ‘Railways Surgeons,’” said one orator at the annual conference, to which the surgeons traveled on discount railway passes. “Our mere summons to service carries with it the thought of a mighty and restless mangling force.”

“They really had to make do with what they had, and they had a sense of pride in that,” says Gillespie. “They felt what they were doing was harder than what most hospitals were doing.”

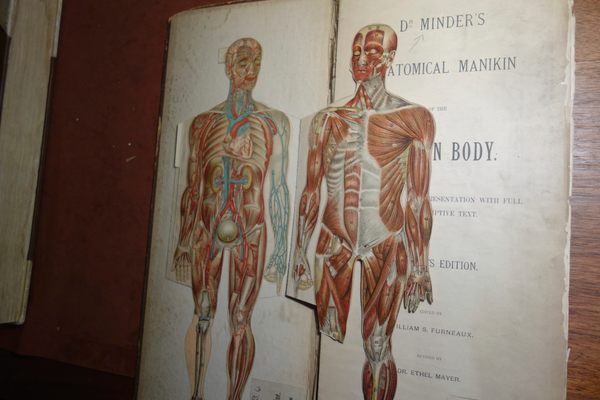

Because of the type of traumatic injuries they were dealing with, railway surgeons developed new techniques and methods. They made their own portable emergency kits, and they were on the forefront of using sterilized gauze and other instruments. They designed hospital cars that could travel to the scene of an accident, which served as models for ambulance train cars used during World War II. In The Railway Surgeon, the journal of the national association, they wrote about foot and spinal injuries, heart surgery, skin grafting, infected fingers, and other, more gruesome insults to the human body. (Once these journals were so rare that Gillespie rejoiced to find a set on eBay. Now a few are available on Google Books and the New York Academy of Medicine holds copies for anyone interested in digging deeper.)

Other medical societies were critical of the surgeons for accepting salaried positions from the railroads, but they were curious enough about the work that they sent spies to the railway surgeons’ conference. Some of the techniques railway surgeons pioneered would appear later in the pages of the Journal of the American Medical Association, the most prestigious medical publication in the country.

The surgeons did consider the question of their obligation to both their employers and their patients, and concluded that they could serve both, even when they were called upon to testify at legal hearings related to accident compensation. Nineteenth-century employers and workers had a different understanding of workplace safety and liability than we have today. The carelessness of workers was often cited as the cause of any accident—they should have checked to see if a train was coming before stepping on that track! In the United States, judges usually accepted the idea that workers had agreed to shoulder the risks of dangerous workplaces when they took jobs. Over the decades when railway surgeons worked, though, primarily from the 1880s to the 1920s, that began to change. In 1908, a new U.S. law made railroads responsible for compensating employees for injury, if a company was found to be at least partially at fault.

But both workers and surgeons exhibited a dedication to their jobs because they believed in the role of the railroads in society. At one time, trains were modern marvels, the height of transportation technology, and the people tasked with keeping them running took their work seriously. “Workers bought into the idea of public service,” says Esbester. “They knew that if they couldn’t get the work done on time, it would cause a delay, and they might take a shortcut. I think it’s important that there’s some agency for the workers involved. They took active decisions very often for really really good reasons, but that had very bad consequences.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook