The Chef Restoring Appalachia’s World-Class Food Culture

A coal fortune is fueling the revival of a cuisine it nearly destroyed.

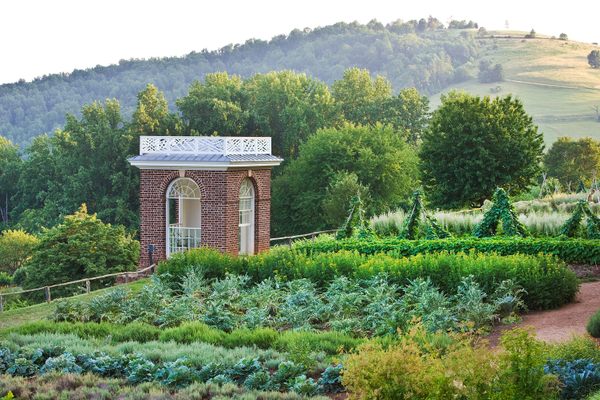

The late-August sun blazes overhead as Travis Milton enters the gated two-acre vegetable garden just steps from Taste, his new brews-and-bistro-style pub. Some 200 yards away, an accompanying fine-dining spot, Hickory, is being built. He walks along a row of heavy, two-foot-long Candy Roaster winter squashes that, when sliced, reveal delicate pink-orange flesh. Elsewhere, ears of Bloody Butcher corn as red as a mountain sunset grow alongside Cherokee White Eagle Corn, which contrast, in turn, with licorice-colored Black Nebula carrots.

The experience feels like touring a high-end botanical garden, but Milton describes it as more of a living-history museum, one that recreates gardens like his great-grandparents’, before it was strip-mined for coal. Most of the more than 100 rare and obscure varieties, he says, were standardized a century ago by homesteaders in Appalachian coal country. All were once regional staples—Milton collected many of the seeds from mountain-country old-timers.

“The diversity of fruits, vegetables, and livestock being cultivated on homesteads in this region was simply astonishing,” says Milton. It was amplified by a tradition of foraging American chestnuts, dandelion leaves, and other wild foods. “If you could’ve brought everything together on one property, you would’ve had one of the largest and most unique region-specific collections of ingredients in the world.”

This, of course, is what Milton is creating now: a farm, garden, drink venue, and restaurant that restore and showcase Appalachia’s world-class food culture. To do it, he’s partnered with Kevin Nicewonder, the scion of one of Appalachia’s oldest and wealthiest coal families. Taste and the farm are now open, and are meant to preview the 28-room Nicewonder Inn and 130-seat Hickory, which will open around June 2020.

With the coal industry disappearing and leaving a gulf of economic disparity, says Nicewonder, “We have to define what this region is going to be moving forward.” He sees the project with Milton as a way to set the bar for future development. “Here, the idea is to tell the story of the land through its food, but with an eye toward healing old wounds.” Rather than doomed efforts to bring back coal, he wants to pursue projects “that will bring positive and sustainable results.”

Milton is from coal country. But to become successful—a star chef, in his case—he left, even shedding his accent. Countless Appalachians have done the same, creating a kind of diaspora, a brain drain. Milton and Nicewonder hope to reverse that, to redefine a region known for poverty, branded as hick, and defined by its dying coal industry as a thriving culinary destination. In truth, though, Milton says, it’s not so much a redefinition as a return to a past that went unappreciated and is almost lost.

“We want to build a beacon that tells people that left the region, or those that’re thinking about leaving: ‘Things are changing. You can put your talents to work here,’” Milton says.

With his great-grandparents’ seeds, and a culture that was nearly strip-mined out of existence, he wants to sow a new future for Appalachia.

Milton was born some 20 miles from the site of Hickory and Taste, in the 2,000-person town of Castlewood. His parents couldn’t afford childcare, so he spent days with grandparents and great-grandparents. His mom’s side ran a diner; his dad’s, a cattle farm. Both kept home gardens and orchards.

“My first memories are being in the kitchen of my grandparents’ restaurant,” says Milton. “It’s my Grandma teaching me to make scratch biscuits, peel potatoes, mix egg batter.” He also rounded up Hereford cattle, shucked green beans on front porches, canned tomatoes, baked vinegar pies, pickled peaches, pruned apples trees, foraged for berries, made preserves, and tended gardens.

“To me, this was just normal stuff,” says Milton. “Everybody’s grandparents kept gardens.”

But when Milton’s parents moved to Richmond, the contrast was glaring. His mountain drawl was a lightning rod for cruelty. He was labeled a bumpkin and teased relentlessly.

“It was like I’d been uprooted and thrown into this hostile, alien place,” says Milton. “To survive, I rewrote who I was.”

He changed the way he dressed and stopped listening to Bill Monroe in favor of David Bowie. He practiced reading aloud to subdue his accent. He took up literature and became a high-school English teacher. But after a year, he took a job as a cook in an upscale Italian restaurant.

“That first night, a light went on,” says Milton. “I said to myself, ‘Okay, so this is what I’m supposed to be doing.’”

Milton rose fast. Within a year he’d been promoted to sous and soon to head chef. The position led to better posts, and he used vacations to apprentice at top restaurants and become a certified butcher and sommelier.

By the late 2000s, though, Milton’s thoughts increasingly returned to Castlewood.

“The more I learned about the restaurant business, the more I appreciated the food culture I’d grown up in,” he says. “My great-grandparents were always tinkering with vegetables and fruit trees, trying to create new varieties that would bring different tastes and textures. I started dreaming of a restaurant that would capture and celebrate that lifestyle, allow me to explore where it came from.”

His idea was not well received by other chefs.

“I’d say ‘Appalachian Cuisine,’ and they’d hit me with a shit-eating sneer,” says Milton. He tells this story in the garden, pausing along a row of trellised vines hung with what appear to be glossy, oversized green beans. “They’d start cracking jokes about toothless rednecks frying up possums and squirrels, or trailer-park trash eating SPAM out the can.”

The beans behind him, Milton explains, are known as Greasy Grits. Hybridized in Appalachian gardens more than 120 years ago, they were prized for making a dried staple known as leather britches. Rehydrated and served in their pods, they bring an unrivaled silky texture punctuated by a sweet and nutty pop.

In 2010, at a New York restaurant, Milton was part of a group planning dishes that would “tell about who we are.” He wondered aloud about sourcing greasies for leather britches.

The following afternoon, the head chef slapped a copy of White Trash Cooking onto Milton’s station. “He got in my face,” says Milton, “and started barking, ‘If this is what you wanna do in my kitchen then you can get the fuck out!’”

Having White Trash Cooking slammed in his face was a turning point. To overcome the stereotypes, Milton realized, he’d need to be able to tell the story of Appalachian food, and give people a taste. But writing on the region’s cuisine was mostly scholarly, focused on single mothers dressing up SPAM in a sugary sauce and other relatively recent ways that plucky Appalachian cooks had responded to the poverty that is, for many, coal’s legacy in Appalachia. And while a few chefs served Appalachian-inspired entrées or appetizers, nobody was doing a full-blown cuisine.

So, in 2010, Milton hit the books. Late at night after shifts, he read online articles, obscure cookbooks, and histories. They led him to chefs, food-writers, farmers, seed purveyors, food-studies professors, and heads of preservation organizations. He wrote emails, made phone calls, paid visits.

Above all, Milton learned that Appalachia was the New World’s first true culinary melting pot. In the 1700s, Germans and Scotch-Irish arrived in what for them was a wild frontier, followed by numbers of English, enslaved people, and freedmen. Settling in small groups for safety and sustenance, mostly in valleys, meadows, and hollows, they found areas inhabited by indigenous groups such as the Cherokee.

The region’s isolation, challenging terrain, short growing seasons, and hard winters broke down traditional social barriers, and forced newcomers from different backgrounds to work together to survive. Subsequently, they adopted each other’s foodways. Though many were infringing on Cherokee lands—and sometimes used violence to secure them, with the U.S. government eventually warring with and forcibly removing the Cherokee—the tendency is most apparent in how the region embraced Native American food.

Appalachian terrain is extremely varied. Small valleys give way to steep slopes and peaks as high as 6,000 feet—many topped with balds and meadows. Europeans typically cultivated single crops in large flatland plots.

“But that method was useless in Appalachia,” says food writer and historian Ronni Lundy, whose 2016 book, Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, offers an experiential history of the region’s cuisine. Though Europeans throughout the Americas learned from indigenous groups, here the effect was amplified.

Lundy says Appalachian settlers adopted Cherokee methods almost wholesale. They hunted wild game, including bison, deer, turtles, and possum. They seasoned meals with herbs such as wild ginger, sumac, and spicebush, and foraged for wild greens, nuts, and berries. Wherever possible, they planted small gardens of beans, corn, and squash using the Three Sisters method.

Lundy calls the Native American’s famous three-crop system “deceptively diverse.” Though statistics are fuzzy, Cherokee gardens are known to have contained dozens of locally adapted varieties of beans. Ditto for corn, pumpkins, tomatoes, and squash. In Victuals, Lundy points to archaeological finds of crops such as goosefoot (a relative of quinoa) as well.

Europeans added their own crops and traditions to the medley. “You had all these incredible ingredients and culinary traditions coming together in one place and combining in new and exciting ways,” says Lundy. Which is why Milton, as a youth in his great-grandparents’ gardens, walked among both beans and squashes from the Americas and Old World fruits and vegetables, picking them to prepare dishes, such as a speckled butter bean cassoulet with rabbit confit, that, in terms of ingredients and cookware, more closely resembled Native potroasts than its French namesake.

Appalachia’s landscape determined its culinary destiny, Milton found, in another important way: The region produced renowned livestock, but a cuisine that did not center around meat.

With its abundant chestnuts, acorns, berries, and alpine sweetgrasses, the mountain wilderness yielded world-class meats (and cheeses) on the cheap. Appalachians let their animals range freely, keeping prized breeds adapted to the landscape. Settlers raised pigs on acorns, berries, and chestnuts, which produced a uniquely flavorful and succulent meat, and helped establish what would become known as the Ham Belt of Tennessee and Kentucky. Meanwhile, says Lundy, German immigrants turned sheep and pigs that roamed at 4,000 feet into delicious sausage. Italians arrived later, bringing their own swine-related techniques and traditions.

“Appalachian livestock and meat products subsequently developed a reputation of superiority and came to be coveted throughout the plantation South,” says Lundy.

But because livestock was so valuable and pasture space so limited, vegetables remained the stars in Appalachia’s kitchens. “Meats were seen more as a flavoring agent or a compliment,” says Milton.

A thriving restaurant scene developed along early-19th century drovers’ roads that connected isolated villages and homesteads to Southern market towns. Most kitchens were run by enslaved people or indentured freedmen and women. The cooks introduced Appalachians to Southern foods such as Hoppin John and African vegetables and herbs including red peas, black sesame seeds, and okra.

Though the Civil War decimated the meat trade—and its related restaurants—the Appalachian ethos of self-subsistence continued. While the rest of the United States specialized and industrialized, linked by growing ports and railroad tracks, using their growing incomes to buy mass-produced ingredients and more and more meat, residents of isolated, largely ignored Appalachia held tight to their gardening traditions.

They were incredible at it. Appalachians crossed Old World apples with indigenous crab-apples to invent now world-famous takes on English-style hard ciders and brandies. Other hybrids—some orange-hued and big as miniature pumpkins, others purple as eggplants—were developed for baking pies, animal fodder, eating, or crafting apple butter. The region subsequently became home to thousands of unique apple varieties.

And that’s just one fruit. Appalachians hybridized varieties of squash, tomatoes, collard greens, you name it.

“These weren’t casual gardeners; they weren’t buying fancy seeds from catalogues and planting them for fun,” says Virginia Tech agricultural extension agent Scott Jerrel. Appalachian gardens were laboratories dedicated to creating new tastes and useful characteristics, like later-maturing squash that grew sweeter with time and kept into the winter. With limited access to sugar, specialty corns were bred to be sweet enough to make delicious cornmeal.

“The approach is very different than [that of most modern] university research programs,” says Jerrel. Most of the time “our primary concern is maximizing yield … [and] shortening maturation times, thereby maximizing profitability for farmers. These people? What they cared about most was taste.”

People like Milton’s great-grandfather took pride in creating specialty varieties of vegetables, herbs, and fruits. A plate of multicolored fingerling potatoes topped with blue, purple, yellow, bright and dark-green rehydrated leather britches, a sprinkling of equally variegated beans, chopped black garlic, and a bright-scarlet dusting of smoked paprika brought fantastic flavors and bragging rights. Many varieties in Milton’s garden have names like Bertie’s Best Greasy Beans.

But the arrival of the coal industry in the late 1800s and early 1900s led to the demise of Applachia’s foodways.

Lured by the money economy, men took jobs in coal mines, moving with their families to mining camps and towns. Though their families kept home gardens to avoid overpriced goods from commissaries, it was a big step away from subsistence. Over time, higher wages combined with better roads made buying from grocers more attractive. The gardens began to vanish.

Though Milton’s maternal great-grandfather turned to agriculture to make money, he didn’t escape the impact of coal. He ran a commercial orchard in Wise County, Virginia, with his brothers from 1911 to 1950. Economic hardships led the family to sell the property to a coal company around 1950, and, like thousands of others, it was eventually strip-mined.

For Milton, visiting the site is a source of painful inspiration.

“It looks like a bombed-out battlefield; it’s impossible to imagine somebody ever grew food there,” he says. “When people talk about bringing back coal, they don’t understand the costs. But I can look at the pictures and see the before-and-after. [Coal] took this amazing orchard and turned it into a barren wasteland.”

But the loss had more than just personal significance. The event coincided with a perilous shift in Appalachian foodways: The region’s amazing culinary history was being buried by historical shifts.

“The rise of big agriculture and the super market economy of the 1950s paired with the collapse of the coal industry to fuel a diaspora,” says Milton. The former had divested younger generations of their capacity to live off the land. Faced with poverty, young families fled to cities looking for work. “The older Appalachian foodways came under pressure.”

As the Depression-era generation began to pass, no one was there to take them up. The foodways were in danger of being lost entirely.

In 2011, Milton assumed the mantle at Richmond’s hip New Southern eatery, Comfort, and made a name for himself with a menu that incorporated traditional Appalachian ingredients.

The farm-to-table revolution was exploding, and interest in Southern cuisine was high. Milton parlayed the attention to feature foods he’d grown up with in southwest Virginia.

“But Comfort had a strong customer-base, so I had to keep it pretty lowkey,” he says. Patrons expected traditional staples such as fried green tomatoes and chicken and dumplings. “The idea was to challenge eaters, but do it gently.”

For example, a stack of fried green tomatoes might bring a medley of mountain heirlooms breaded with Bloody Butcher cornbread instead of flour and a topping of strawberry-rhubarb relish. A collard greens dish might include heritage varieties such as Champion and Alabama Blue, and be paired with leather britches made from Pink Tip Greasy Beans, cubes of grilled Candy Roaster Melon Squash, and bacon crumbles from a West Virginia Tamworth pig.

The response was cult-like. Area food critics crowned Milton one of the city’s top chefs.

In 2015 he shocked the culinary world by accepting an offer to develop Comfort-esque eateries at two new boutique hotels in the heart of southwest Virginia coal country. The collaboration led to an eponymous restaurant in the hip and offbeat Western Front Hotel in the 1,000-person town of St. Paul, which was devastated by the near-total loss of regional coal jobs in the early 2000s. Situated deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains on the Clinch River, the hotel and eatery is at the center of the town’s effort to overhaul its economy around outdoor tourism.

For Milton, the move was all about location—it wasn’t enough to be sprinkling Appalachian touches on the menu of a restaurant in the state capital. “Travis understands that you can’t extract the cuisine from the culture,” said John Fleer, chef-owner of Rhubarb in Asheville, North Carolina, to the Washington Post in 2016. Revitalizing Appalachian cuisine required relocating to the region.

But the projects had other goals too. They marked the first step of Milton’s plan to bring culinary-based economic development to a region decimated by the loss of coal jobs.

“Restaurants hire and train workers and, if they source local, support area farmers and food artisans,” says Milton. Visitors bring dollars that drive tourism-related businesses—including pick-your-own berry farms, ATV tour companies, fly-fishing and canoe outfitters, farmer’s markets, breweries, cideries, distilleries, and additional restaurants.

“There are so many talented people out there that, like me, grew up here, miss this place, and would love to find a way to come back,” says Milton. Hiring for sous chefs at Western Front brought about 150 resumes; 75 percent came from Appalachian expats living in cities such as New York and San Francisco. “My hope is that these projects will convince some of them to bring their [real and creative capital] back to Appalachia.”

Nearly 70 years after his great-grandparents’ garden and orchard was strip-mined, Milton decided to partner with Kevin Nicewonder, the coal-family scion, to do that in an even bigger way.

Milton calls his project with Nicewonder the spearpoint of a crusade to spread awareness about and revitalize Appalachia’s endangered historic foodways. In addition to the garden and two restaurants, heritage breed sheep, cows, pigs, chickens, and turkeys will roam forest-lined pastures throughout the 800-acre property. He plans to add berries, fruit, and nut trees as well.

“Kevin has provided the space and resources I need to create a flagship venue that goes well beyond the scope of a traditional restaurant,” says Milton, drawing comparisons to Tennessee’s famous culinary destination Blackberry Farm. “We want to teach eaters about [Appalachia’s] history and story, and let them experience it through taste.”

Milton calls the symbolism of the partnership with Nicewonder fundamental.

“The coal fields drove the region’s economy for a long, long time,” says Milton. But the environmental and social costs were disastrously high. “To me, this is a demonstrative effort to heal and move forward. I’m not calling it reparations, because it’s not. But it is a statement. This project is saying, ‘Look, that was the old way. And this is the new way, this is the future.”

Once again, Milton likens the project to a beacon for the region. He sees Taste, Hickory, the garden, and farm as a training ground for high-end waitstaff, mixologists, chefs, and small-scale farmers who will go on to work at and with other Appalachian-themed restaurants—or even better, open businesses of their own.

“This isn’t easy work,” says Milton. Training waitstaff to explain the cultural heritage of hundreds of obscure vegetables is challenging in a region where poverty rates hover around 25 percent. “But I love this place and I’m passionate about it,” Milton asserts. “I dream of a future where young people are coming back to take over their grandparents’ farms and plant apple trees on strip-mined mountaintops. And we’re starting to see that happen.”

Because with each addition, says Milton, the beacon shines a little brighter.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook