When the Māori First Settled New Zealand, They Hunted Flightless, 500-Pound Birds

The magnificent moa is no more.

When one thinks about iconic New Zealand birds, the one that comes to mind is invariably the fuzzy brown kiwi. But lost to time is another bird, one that long ago loomed over the chicken-sized kiwi. Enter the moa: nine species of flightless bird that once sprinted around New Zealand. While the smallest, such as the turkey-sized bush moa, were fairly petite, the South Island giant moa clocked in at two meters (6.5 feet) tall. In its time, it was the tallest bird to walk the earth; larger females weighed more than 500 pounds. With their long necks, rotund bodies, and total lack of wings, they must have been an imposing sight. And for the Polynesians who arrived in canoes on the shores of New Zealand in the 13th century, they were a delicious one.

Before the arrival of humans, New Zealand was the land of the birds. In place of large carnivores, of which it had none, an avian hierarchy flourished, from the burrowing mutton birds to the gigantic but now extinct Haast’s eagle, which perched at the top of the food chain. Despite being prey for the Haast’s eagle, moa proliferated across New Zealand, inhabiting different ecosystems suited to their size and diets. The South Island giant moa could reach high branches, and the heavy-footed moa stuck to “open herb fields.”

This hierarchy was upended with the arrival of the people now called the Māori. Starting in Asia, most likely Taiwan, Polynesians traveled across the Pacific for thousands of years, populating islands along the way. New Zealand was the last stop, and the last major, uninhabited landmass to be settled by humans. For food, the new settlers brought taro and yams, some of the traditional canoe plants of the Polynesians, along with rats and dogs for meat. But New Zealand proved to be fertile hunting grounds.

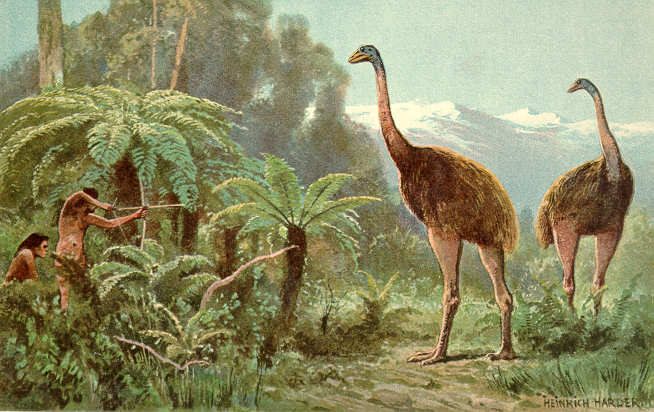

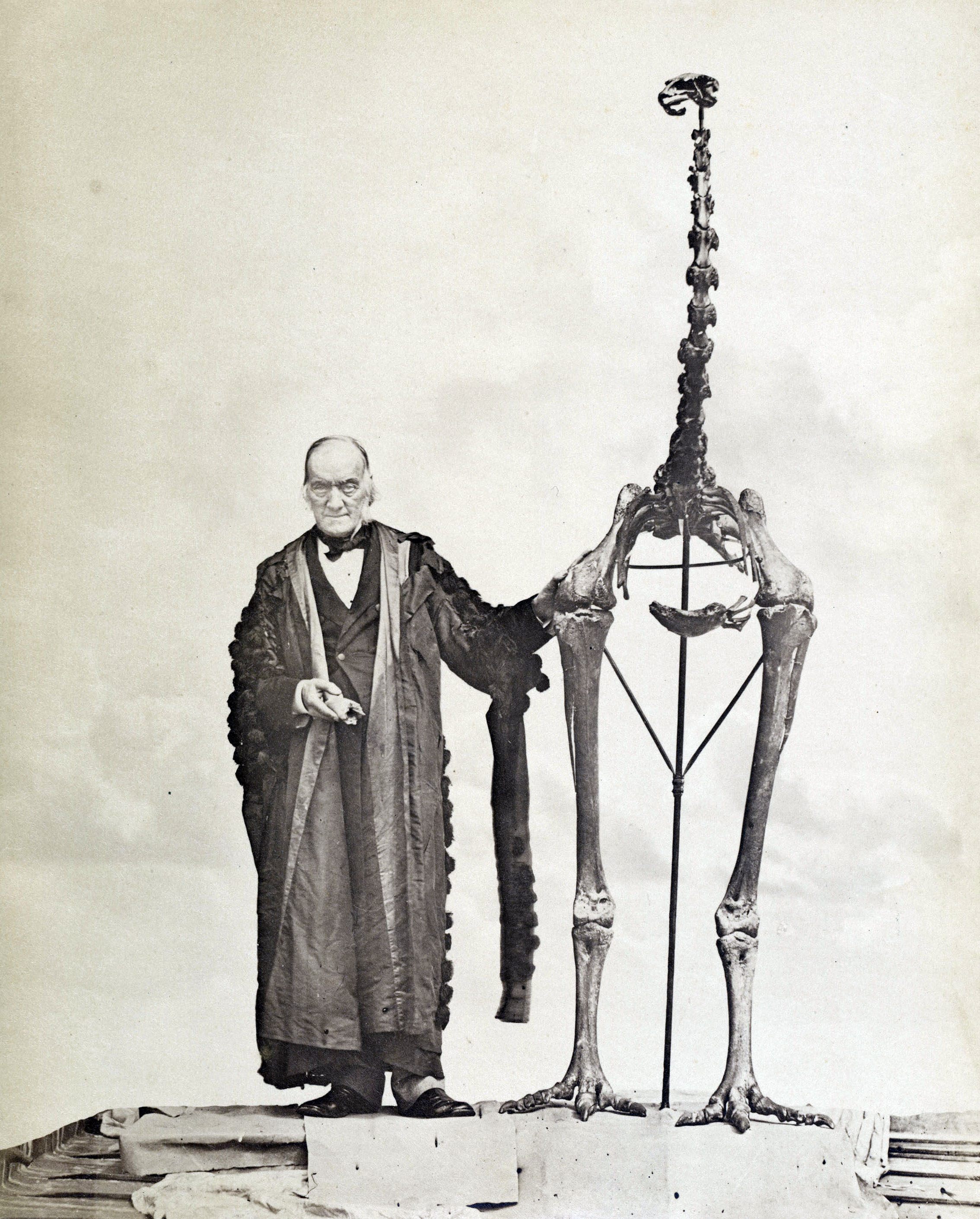

Lacking any wing bones, moa couldn’t fly away from their new foes. But, considering their large leg bones, much speculation has been made over their speed, not to mention the power of their kicks. (Mark Twain, on seeing a moa skeleton, wrote, “It must have been a convincing kind of kick. If a person had his back to the bird and did not see who it was that did it, he would think he had been kicked by a wind-mill.”) Since newly arrived Māori hadn’t yet developed bows, hunting these large birds took some creativity.

For researchers, piecing together how moa were hunted has been an equally creative process, combining archeological and anthropological findings. To avoid contact with the larger moa, some researchers believe the Māori used snares to tangle up their prey, which was considered the traditional “Māori fowling method.” One prehistorian points to the Māori dog’s “strong neck, forequarters, and jaw” to conjecture they were bred to seize large game, including moa. Another historian, skeptical that dogs could handle these massive birds, has speculated that dogs helped drive moa to inescapable locations where they could be cornered and killed.

Hunts started from base camps that served as butchering sites. The enormous quantity of left-over bones buried in middens reveal key facts about how the Māori dealt with up to 500 pounds of dead moa. While smaller moa could be carried away whole, hunters dealt with larger ones, which were harder to heft, by cutting and carrying away only their meat-heavy legs. “It is tempting to imagine a line of successful hunters with giant drumsticks over their shoulders,” writes James Belich in Making Peoples: A History of the New Zealanders.

In a recent study, three New Zealand scholars examined Māori sayings, or whakataukī, for clues about their relationship to moa, including cooking techniques. One, He koromiko te wahie i taona ai te moa, or “Koromiko is the wood with which the moa was cooked,” likely meant that koromiko branches were used to cover moa meat cooking in underground ovens. Researchers and scholars, who can only contemplate the moa’s formidable skeletons, have long speculated on how the bird tasted—their fattiness and their flavor. Most recently, researchers have conjectured that moa tasted similar to their closest relatives, the flightless tinamous of South America. Ironically, many species are over hunted because of their tasty meat.

When Polynesians first arrived in the 13th century, an estimated 160,000 moa roamed New Zealand. But they were annihilated within 150 years, in a process one study calls “the most rapid, human-facilitated megafauna extinction documented to date.” After all, moa had few natural predators (other than the giant eagles) and may not have been very afraid of humans. They lay few eggs—only one or two every breeding season—and took a long time to reach maturity. The Māori hunted them faster than they could reproduce, until they were gone.

While their demise was unusually fast, the disappearance of the moa was par for the course for human history. As early humans spread across the earth, they persistently hunted down the largest beasts around. Along with climate changes and human-caused ecosystem change, many researchers implicate hunting as a death knell for creatures from the giant ground sloth to the wooly mammoth. From this perspective, humanity’s late arrival to New Zealand simply delayed the moa’s execution date. By 1769, when Captain James Cook arrived on the shores of what is now New Zealand, the birds were long gone.

When British naturalist Richard Owen confirmed the existence of the moa in 1839 from a single bone, it created something of a moa craze. After all, moa were as unique as the kiwi, as extinct as the dodo, and more monumental than any other bird. Twenty years later, a workman unearthed the largest moa egg ever known: the Kaikoura egg, which had been nestled next to a body in a grave. It likely weighed almost nine pounds when fresh, and is now on display at the Te Papa museum in Wellington. From perfectly preserved feet to their very footsteps, remnants of the moa continue to be discovered. While they live no more, it’s hard to erase the existence of such an epic avian.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook