Why Is Mischief Night Different From All Other Nights?

How a local tradition has hung on for centuries.

In 2013, graphics editor Josh Katz created what would become that year’s most-visited New York Times story: a linguistic quiz for Americans. “I was studying statistics, and I’ve always found linguistics interesting,” he says. “So it seemed like a dataset that would be interesting to apply some statistical methods to.” That quiz, with uncanny accuracy, can guess where an American is from based on a series of dialect questions by matching answers to the results of a survey. Some of these are classic, diagnostic matters of pronunciation (like whether “cot” and “caught” sound the same), while others are based on local curios, different words for the same things (like what you call the strip of grass between a sidewalk and a road, if you call it anything at all).

One of the strangest results of the survey was in this question: “What do you call the night before Halloween?” That map shows three main answers. Most of the country—from Maine to Florida, Los Angeles to Seattle, the Great Plains, Big Sky, and Deep South—replied: “I have no word for this.” Another was highly localized in Michigan, and another was focused on Philadelphia and New Jersey, with little splinters into Delaware and New York.

Katz, it’s probably worth noting, is from the Philadelphia suburbs of South Jersey, right in the heart of the hotspot of “Mischief Night.” Mischief Night is so common as a term there, so built into the season and the place, that those of us from this area—I’m from southeastern Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia—continue to be shocked that this is a local phenomenon. “Mischief Night had always been one of those things that I remembered from growing up,” says Katz. “I feel like it wasn’t until I went off to college that I found out that the night before Halloween wasn’t called Mischief Night everywhere in the country.”

It’s not just that it’s called “Mischief Night” in that region and something else in other parts of the country: Mischief Night literally doesn’t exist anywhere else in the United States. It was like finding out that the rest of the country had never heard of placing foods in between two slices of bread.

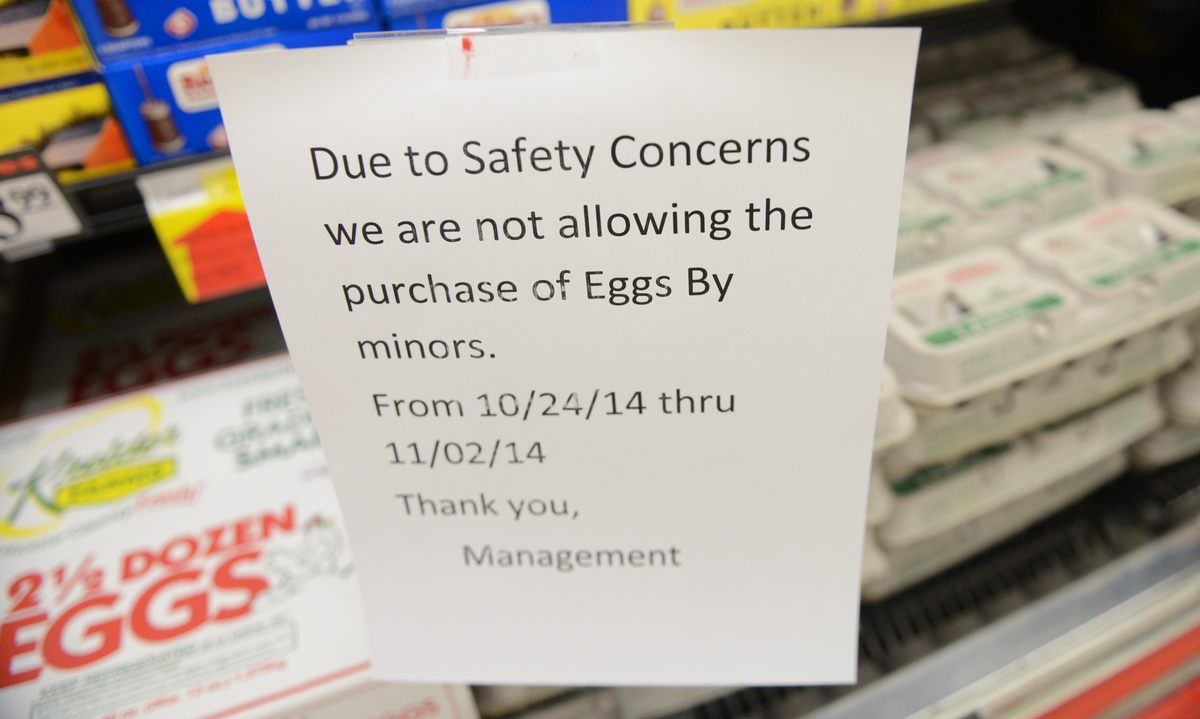

Mischief Night, in my Pennsylvania suburb and in the New Jersey towns of several people I spoke to, involved mild pranks committed on October 30. The perpetrators—typically those who had just aged out of trick-or-treating, so early teenagers—would throw rolls of toilet paper over houses and trees, maybe ring a neighbor’s doorbell and sprint away before the door was opened, maybe throw some eggs at a window. It was, in my memory, discussed far more often than it was actually seen. (Some of these common pranks, or tricks, are more reserved for Halloween itself in many other places.)

“To be perfectly honest, the idea that it’s highly localized to New Jersey and southeast Pennsylvania, I only learned that recently,” says Angus Gillespie, a professor of American Studies at Rutgers University who has taught classes on American folklore. In fact, Gillespie has specifically focused on New Jersey folklore, because so many of Rutgers’ students are from the state, and still wasn’t aware just how local the tradition is. That Mischief Night isn’t a universal experience is deeply strange to those of us who grew up with it—not because Mischief Night is unusual, but because it’s so ordinary. This, confusingly, makes Mischief Night much more interesting than it ought to be.

Mischief Night is first attested to in the 1790s, but almost certainly dates back significantly earlier than that. In her 2012 dissertation at the University of Bristol, about the history of Halloween in Northern England, Karen Allen writes that an autobiography of labor advocate and writer Samuel Bamford (b. 1788) includes a description of Mischief Night that mentions pranks like pulling up fence posts and tipping over horse carts. The response to the pranks Bamford describes indicates that these activities were likely already tradition, and that they were treated about the same way that today’s pranks are treated, with a mixture of mild annoyance and acceptance. “Oh, it’s nobbut th’ mischief-neet,” reads one response. No big deal. Kids being kids.

Other pranks from around this era include greasing doorknobs with lard, knocking on doors and running away (“ding dong ditch,” in the United States, “knock down ginger” or several variants in the United Kingdom), and removing a gate door from its hinges. Uprooting fence posts seems to have been one of the most common pranks, perhaps an odd choice given how much physical labor it would require.

Mischief Night, or neet, appears to have been most popular in Northern England, particularly in the counties of Yorkshire and Lancashire. According to Allen, though, it was not originally associated with Halloween, but rather with May Day, a very old festival signaling the beginning of summer. There is already, by the early 1800s, some public panic about the rebellious nature of Mischief Night, which seems to have been (or seen as, by adults) a time for both vandalism and sexual encounters.

But Mischief Night is nothing if not flexible. It moved around several times over the centuries. By the end of the 1800s, and into the first few decades of the 1900s, Mischief Night shifted from April 30 to November 4—from the eve of May Day to the eve of Guy Fawkes Night. Allen suggests, though she notes that there’s no hard evidence for this, that the shift was a result of increasing industrialization in places like Leeds. With less reliance on the agricultural seasons that made May Day vital, the eve of Guy Fawkes Night had several benefits. For one thing, the night is longer (by close to three hours), which is conducive to pranking. Guy Fawkes Night, commemorating the failure of a 1605 assassination attempt on King James I, was also associated with mischief and sometimes violence itself; a fundamental part of the celebration is burning effigies of enemies.

Mischief Night appears to have operated simultaneously on April 30 and November 4 for a while, depending on a community’s folklore, but by the early 1900s it was firmly established as an autumnal event in Northern England. Interestingly, Guy Fawkes Night was likely inspired, at least in part, by Samhain, the much older Gaelic festival signaling the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter. Samhain, like Guy Fawkes Night, involves lighting huge bonfires (probably started as a way to get rid of all the agricultural waste following harvest), but Samhain also has associations with spirits, ghosts, faeries, things like that. It was considered a time when the barrier between our world and the spirit world was especially thin.

So Guy Fawkes Night is probably influenced by Samhain. Samhain eventually transforms into All Hallows’ Eve, which becomes known as Halloween. And Guy Fawkes Night has been mourned by some British writers as a lost British tradition, overrun by imported American Halloween traditions.

During all these changes, Mischief Night tagged along. And there’s a reason it persisted: Mischief Night serves a purpose. It is one night a year when age roles are reversed, and kids have power. It’s a single day when kids are permitted to rebel, at least a little bit, and to let off steam. And it works out fine for adults, too, since it’s only one day, and the pranks are really pretty mild. This isn’t The Purge; it’s toilet paper. This might explain why the attitude of adults to Mischief Night, whether in Yorkshire in the 1790s or Chester County, Pennsylvania 200 years later, is one of bemused tolerance.

None of this, though, explains why Mischief Night is so heavily localized within the United States. In Katz’s map, it is firmly in and around Philadelphia, and South and Central New Jersey (the latter of which may not be real, but that’s a different article), and bleeds a bit into surrounding areas. Michigan has its own version, Devil’s Night, which has its own history.

Devil’s Night appears to center around Detroit in the same way Mischief Night centers around Philadelphia, and had many of the same traditions (toilet paper, graffiti, egging) for decades. Unlike Mischief Night, though, the Michigan version often hewed closer to Guy Fawkes Night, specifically its bonfires. These were largely harmless at first, but by the 1970s, dozens and sometimes hundreds of fires erupted in Detroit that night each year, and are probably more accurately described as arson. In 1994, Detroit’s mayor vowed to put a stop to the fires and declared that the night before Halloween would be called Angel’s Night. Angel’s Night was sort of a policing program involving curfews, citizen patrols, and a great deal of stop-and-frisk activities.

The 1994 attempt to curtail Devil’s Night was not the first. There was also one in 1976 and throughout the 1980s. Regarding the 1983 curfews, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) denounced the policy as a racially biased attempt to control non-white Detroiters. As the ACLU reports about one arrest incident: “It was clear through the ACLU report that these teenagers were in the arcade and not causing disruption, violence, or destruction. They also were not approached until after their curfew expired at which time the police arrested them along with the other 25 graduates, all of which were African American teenagers, out past this regulation time.”

The ACLU also describes some of the attitudes toward Devil’s Night: “Devil’s Night antics characterized the more common fear among the citizens of Detroit, which was rogue juvenile delinquency exacerbated by underpolicing, a mob mentality, and access to weapons or other dangerous objects.”

Both Philadelphia and Detroit were, by the 1980s, predominantly Black, with white populations having left the urban centers following World War II in patterns of white flight. It’s worth noting that in the white suburbs, Mischief Night was genially tolerated. This was not the case in the cities.

In England, Mischief Night pranks in November have decreased as Guy Fawkes Night has declined in popularity. But they do continue, especially in Northern England, only now tied to Halloween in the same way they are in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. It’s kind of an export that’s been re-imported.

Halloween itself was not widely celebrated in the United States until the early 1800s. Ghost stories and gothic tales began to rise in popularity, most notably in the curiously Halloween-free “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” but the prominence of the holiday can be tied to waves of immigration. A huge number of people sometimes called Scots-Irish migrated to the United States in the late 1700s and early 1800s. “Scots-Irish” is a terrible descriptor for a diverse group of people from the British Isles. Probably most of them had Northern English and Scottish Lowland roots, from around the border there, who had moved to Ireland in the 1600s. But they stayed for only a few generations before many of them moved to the United States as a result of drought, famine, and political and religious obstacles to owning land in Ireland.

They came, almost entirely, to Philadelphia. This may have been partly because of Pennsylvania’s tradition of religious tolerance. They were Protestants, and would have encountered difficulties in Catholic Ireland. Philadelphia was also the largest city in the country for most of the 1700s, and remained close behind New York City for the rest of the period of intense Scots-Irish migration. The influx had a major influence on Philadelphia, but only for a few decades. Many of the migrants then moved west and, especially, south, into Appalachia and the Southeast.

Halloween and Mischief Night weren’t associated with each other at this point, but they were both most celebrated in the places where the Scots-Irish came from. Halloween first appears in the United States around the middle of the 1800s, though it’s described in accounts of the mid-to-late 1800s as a sort of genteel British thing. But almost immediately, discussions of Halloween are accompanied, if you read between the lines, by the practices of Mischief Night. In magazine stories about bobbing for apples and fortune-telling parties are tales of kids—usually boys—dinging, donging, and dashing, or throwing old cabbages at houses. (“Cabbage Night” remains a sort of arcane and not-widely-used term for Mischief Night; Katz’s map found a few Cabbage Night responses around New York City.)

Here’s a passage from an 1898 edition of the newspaper The Daily Signal, a short-lived Ohio newspaper not to be confused with the modern conservative publication put out by the Heritage Foundation:

“Miss Maud Dowling gave a pretty Halloween party last night to a number of friends, the evening being an enjoyable one. Miss Dowling proved herself a charming hostess, entertaining her guests in a novel way. While they were seated at the supper table, the small boy who will play his obnoxious pranks on Halloween, drew a large wagon filled with tin cans and old buckets, up to the hostess’ house and began throwing the noisy articles in the yard. It was great amusement for the guests but very annoying for Miss Dowling.”

Over time, Mischief Night was mentioned more often in local papers and, eventually, television news affiliates. Teens running rampant and playing pranks—Maybe they’re violent! Who knows!—has always been catnip for local news. Evidence for actual damage from Mischief Night, apart from the fires in Detroit and a few flare-ups like Camden, New Jersey’s 1991 Mischief Night, which saw more than 160 fires, some of them large, is minimal. One New Jersey native, who asked not to be identified by name, related this story: “One of the funniest things I remember is my cousin, who was always super afraid of getting in trouble, toilet-papered his own house. He figured that way he’d have some street cred, but [with a] low risk of a run-in with an angry homeowner.”

Katz, for his part, pauses when asked if he had ever participated in Mischief Night. “I feel like I’ll have to plead the fifth on that one,” he says.

Halloween clearly spread to be a beloved holiday across America, but not so Mischief Night. There are no clean answers for why it stayed so sequestered. Halloween and Mischief Night are a weird conglomeration of different traditions from different parts of Europe that sent immigrants to the United States: Samhain from Ireland, Guy Fawkes Night from England, Walpurgis Night from Germanic countries, and probably a whole bunch of others. There is no one simple reason why this small part of the United States has preserved a very old tradition while nowhere else has.

Pranking as a general theme is fairly universal in American Halloween. It’s built right into “trick or treat,” though the threat is rarely carried out. Mischief Night’s pranks aren’t unusual, either; toilet-papering and ding-dong-dashing are pretty standard. What makes Mischief Night unusual is the separation from Halloween itself. In most of the country, pranking and Halloween have smushed together, while in Mischief Night territory, they remain separate.

The reasons for this aren’t clear, but that doesn’t mean we can’t speculate. Certainly the Scots-Irish history in Philadelphia plays a role. Perhaps the lower population density of Appalachia and the South, where many of them moved, wasn’t conducive to pranks, halting the spread of the practice. Mischief Night had taken off in Britain with industrialization and increasing population density. Cities and suburbs are ideal for pranks, because they provide many targets within walking distance, enough population that pranksters can maintain relative anonymity, and a built-in audience for one’s audaciousness or imagination. You can’t prank your neighbor if he lives a mile away. It’d be a real slog, no one would see it, and they’d know it was you anyway.

There’s also a squidgy sort of theory about Philadelphia, which is that Philadelphia is an extremely provincial city in—let me be sure to add—a really lovely way. Of all the major cities—Philadelphia is sixth largest, just barely behind sprawly Phoenix—Philadelphia has by far the highest percentage of people who currently live there who were born in the metropolitan area. A whopping 68 percent of Philadelphia residents were born in Pennsylvania, compared to less than 50 percent in New York City and Los Angeles, and even less in Phoenix and Houston. This isn’t a great metric, because some of these large cities lie near state boundaries (including Philadelphia), but either way, Philadelphia is dramatically Philadelphian. The city’s culture concentrated, like a reduced sauce, in the decades following World War II. The population dropped dramatically, and those who stayed either couldn’t or wouldn’t leave. That’s changed in the past decade, but it takes longer than that for a culture to change. “This is going out on a limb, but I think our region is more tradition-oriented than other regions,” says Gillespie.

Philadelphia is aggressively local about its traditions. You can see this in the high percentage of local foods, in the unusually fierce sports fandoms, in a local accent so weird and insular that it’s perhaps the most-studied regional accent in the country. It is not a static place, especially not recently, but certain traditions do tend to stick there, harder and for longer, than they do in other places. I suspect Mischief Night found a place with the right people and the right attitude to survive.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook