Unearthing Portugal’s Wine of the Dead, a Relic From the Napoleonic Wars

The invasions led to an unexpected discovery.

In the small town of Boticas, Portugal, a centuries-old tradition of making “wine of the dead” lives on. Despite its macabre name, this libation has less to do with death than it does with burial. In 19th-century Portugal, during a time of French invasions, people interred scores of bottles. The move, done out of fear that the wine would fall into enemy hands, led to an extraordinary discovery once the dust had settled.

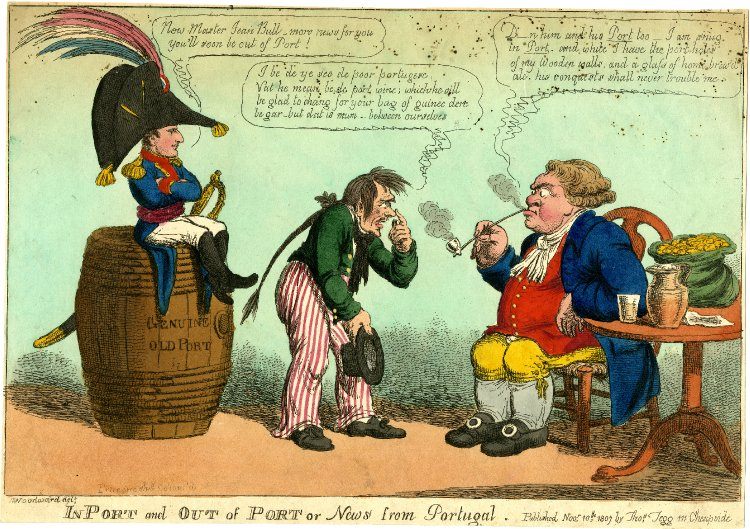

In 1807, Napoleon Bonaparte’s army first started the march towards Lisbon. It was an attempt to force Portugal to join the Continental System—essentially a large-scale embargo against British trade. Despite Portugal’s precarious isolation, and its place on the edge of a continent that bowed to Napoleon’s rule, it had refused to join. They would refuse again, choosing instead to honor a long-lasting alliance with the United Kingdom.

The French took Lisbon in November, but by then the Portuguese royal family had sailed off to Brazil, hoping to establish the capital across the Atlantic and maintain a bureaucratic semblance of independence. Unimpressed by this abandonment, and exhausted by the French’s freshly minted taxes and old-school plundering (this was an army that marched on its stomach, and favored stolen local wine to wash it all down), people grew restless under occupation. Movements of popular resistance popped up all over the country, but when the United Kingdom intervened a year later, the French went away.

Napoleon wasn’t keen on the news. As long as Portugal remained aligned with the United Kingdom, the latter would have a point of entry into what he believed was his continent. By March 1809, the second invasion was underway, and the French army entered Portugal from the north, hoping to secure the country’s second largest city, Porto. Again they left behind an unrivaled trail of sacked and ruined communities, but not everyone was caught unaware: Boticas, a town of a few hundred inhabitants, had plans for a passive-aggressive mutiny up its collective sleeve.

Well aware of the French’s fondness for pillaging wine, the population rushed to the cellars and buried every last bottle in the gravel underneath the barrels, far from the greedy hands of the invading army. It’s likely the French felt parched when marching through Boticas afterwards, but the forced sobriety did little to change the outcome of the invasion. The French would go on to conquer Porto, yes—but thanks again to the British, they wouldn’t stay long.

But Napoleon wasn’t done with Portugal yet. The final invasion that began in 1810, through the eastern border, was arguably the most disastrous of the three: The French were up against an organized Luso-British defense, and although they managed a significant advance towards Lisbon, they couldn’t get past the newly fortified surroundings.

Meanwhile, those proverbial Napoleonic stomachs were battling the discouraging reality of a scorched-earth policy. The British had ordered a full evacuation along the route of invasion, complete with the destruction of any food supplies that couldn’t be carried away, and the Portuguese population had been all too happy to comply with the adage “if you can’t beat them, starve them.” By March 1811, the exhausted French and their imperial dreams had given up and retreated to Salamanca, Spain, never to be seen again.

Yet several years of consecutive invasions had left Portugal in a dire condition. In the aftermath, they coped with a tremendous loss of lives and monumental damages to agriculture, industry, and commerce throughout the nation.

Things were looking up in the small northern town of Boticas, though. Initially fearing their buried wine had spoiled after its impromptu underground stint, the locals dug up the bottles around March or April 1811. They were astonished to discover that low temperatures and darkness had, incredibly, improved its taste instead. The resulting wine was lighter, fruitier, and just a little fizzy, due to an accumulation of carbon dioxide. It didn’t take long for this happy accident to turn into a tradition, though it’s hard to pinpoint when it found its popular name, “wine of the dead,” as a nod to all those months spent in darkness.

Winemakers around the world have reached similar conclusions regarding the benefits of wine burial. In Georgia, wine is aged in buried, amphorae-like vessels called qvevri. And in France, wine tastings can come with a side of spelunking, down into caves where a handful of winemakers have taken to aging their wares. Wine cellars are damp and dark, it would seem, for a good reason.

In Boticas, much of this tradition was lost over time. Were it not for a concerted local effort to protect and promote the wine of the dead, this tale of anti-Napoleonic resistance could very well have stayed underground. A protected designation of origin was created in 2006 for wines produced in the Trás-os-Montes region, where Boticas is located. Soon afterwards, in 2008, the town built a museum to showcase the history of this seemingly macabre wine.

As for the name itself, the trademark “Vinho dos Mortos” (wine of the dead) is currently owned by the local farmers’ co-op, and only one winemaker is allowed to use it. Armindo de Sousa Pereira, whose parents and grandparents previously produced and sold wine of the dead, is the lucky holder of said permit. He says there’s been a recent and renewed interest in his wares, and although he’s happy with the growing demand from foreign connoisseurs, he’s in no rush to start exporting.

He’d rather foreigners came to him—and they’ll surely find a better reception than Napoleon’s soldiers did when they first tried to set foot in Boticas more than 200 years ago.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook