The Sargasso Sea Is Plenty Wide, and It’s Growing

What happens when you have too much of a good thing.

Sargassum is like red wine or cologne. It can be very good in moderation. Sargassum is the umbrella term for a group of marine algae species—within a larger group called seaweed—that’s fundamental to the health of an entire region of the Atlantic and the many species who either live there or pass through. Sometimes, though, it explodes in growth, creating a continent-sized bloom that thoroughly freaks out multiple countries. These blooms have long happened and are perfectly acceptable if they happen rarely. They have not been happening rarely.

There were huge blooms in 2011, and then 2014, 2015, and 2017. In 2018 and 2019, the blooms were much bigger than they had been before 2011. “Prior to 2011, there was almost no sargassum impact in the Caribbean,” says Chuanmin Hu, a professor of optical oceanography at the University of South Florida who has studied sargassum for about a decade. “So yes, in the long-term history, this is very unusual.”

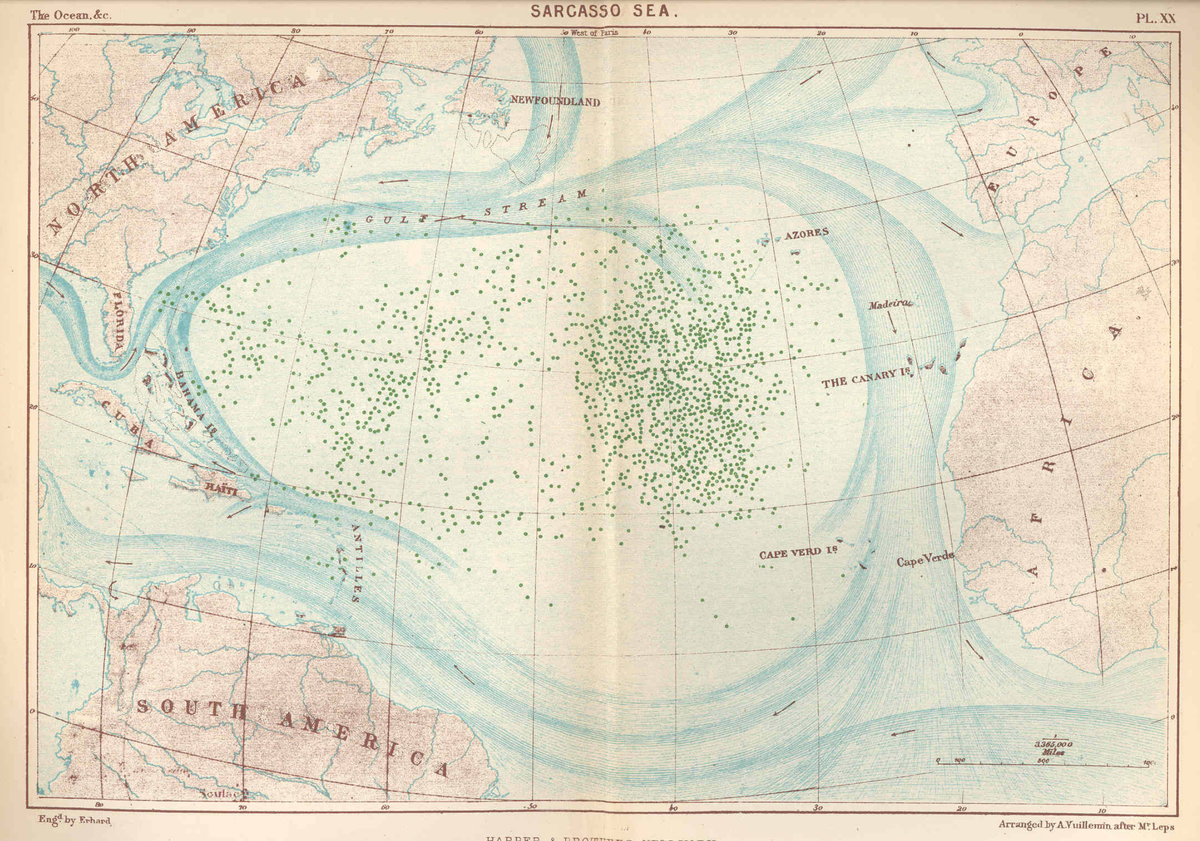

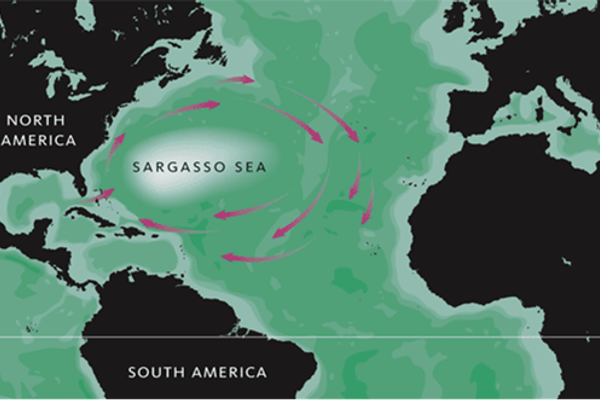

Sargassum gives its name to the Sargasso Sea, located in the Atlantic, north and east of the Caribbean. It is a truly unusual place, the only location given a proper “Something Sea” name but with no land boundaries. Instead it’s bounded by currents, including the all-powerful Gulf Stream, which runs up the East Coast of North America. These various currents bring in and then trap anything that floats within that portion of the Atlantic, creating both the Sargasso Sea and the North Atlantic Garbage Patch.

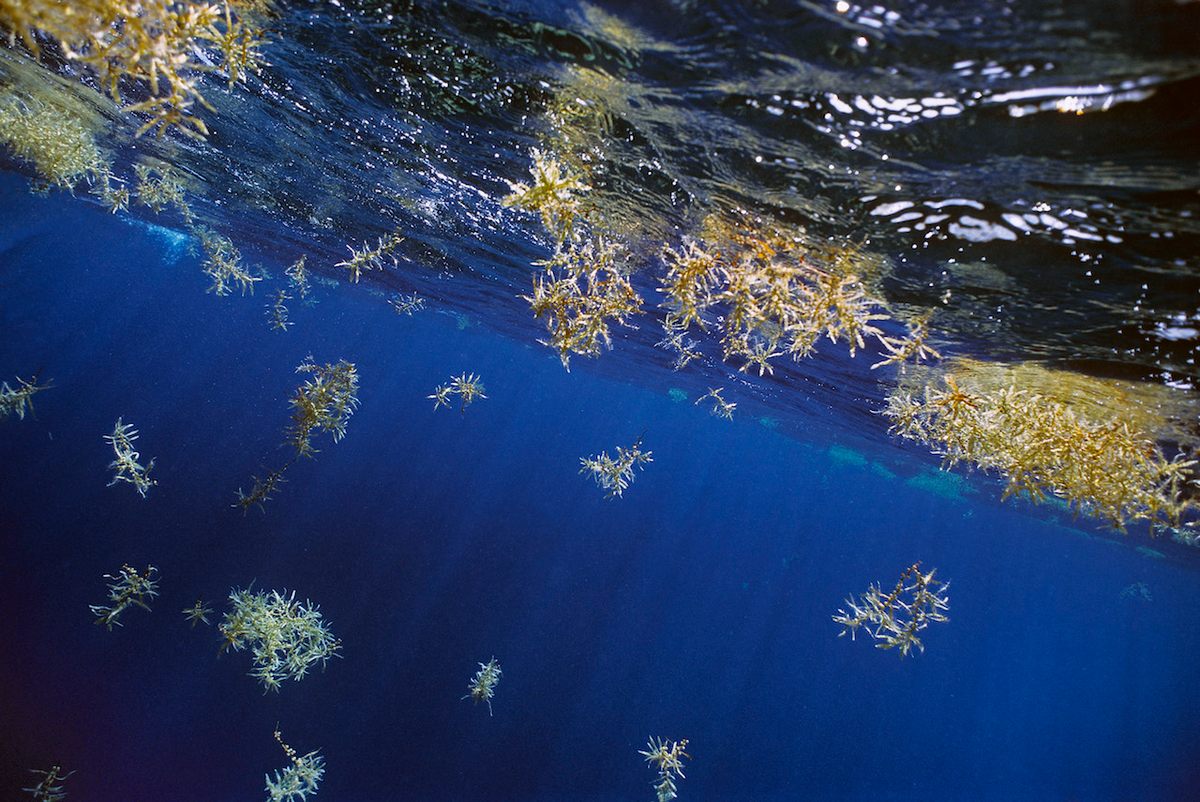

The Sargasso Sea is about a thousand miles wide and three thousand miles long, roughly the size of the United States. Scattered across this sea are huge mats of sargassum, floating with the aid of grape-like bubbles of trapped air that act as little buoys. Because it’s free-floating, the sargassum moves around, making it tough to measure. It also reproduces while out at sea. It does this vegetatively; a piece of sargassum detaches and grows from there, kind of like the way you’d propagate a pothos or succulent houseplant.

Because this sea has no land around it, and the water is quite deep throughout, it does not at first glance seem to be much of a habitat for animals. And yet it is, because in the absence of real islands, huge floating rafts of sargassum become de facto land masses, shallows, places of shelter.

A whole host of species live some or all of their lives hidden among the gigantic floating pads. Many of these animals have evolved to look pretty much like the sargassum itself. Various shrimp and crab species, small fish, sea slugs, various eels, and even baby turtles come to take cover within the impenetrable maze of yellowish-brownish plant matter.

“In the ocean, sargassum has been regarded as a critical habitat,” says Hu. Most of the species that live in and sargassum are found nowhere else on Earth. And sargassum is also a fairly efficient carbon sink; it sucks in carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it. This is all to say that under normal circumstances, sargassum is widely considered very good, providing all sorts of useful ecological functions.

Over the past decade, we have not been experiencing normal circumstances. It is natural for sargassum to eventually blow westward and die, and end up on the beaches of the Caribbean, from South Florida to Aruba. This is part of sargassum’s life cycle, and Hu compares it to leaves on deciduous trees turning brown and falling in the autumn. But something has been changing in the past few years, and those dead and dying masses of sargassum have exploded in quantity. “When you have a very large quantity of sargassum, either on the beach or in coastal waters, then you have a problem,” says Hu. Hu’s team tracked this washed up sargassum to a strip they’re calling the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, a larger area than the Sea, stretching all the way from West Africa to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Sargassum has always lived in these areas outside the Sargasso Sea, but never before in these quantities. Since 2011, it’s all become an essentially uninterrupted, massive strip—tens of millions of tons of seaweed that weren’t there before.

Excess sargassum can cause any number of problems. The algae floats when the mats are alive, but when they die, they sink. That can lead to suffocating blankets coming to rest atop delicate ecosystems such as coral reefs. Even worse, bacteria in decomposing sargassum suck oxygen out of the environment. Coral reefs in the Caribbean are struggling to survive as it is, and fundamental coral species have already been listed as endangered.

The problems don’t stop at water’s edge. Sargassum has always washed up on Caribbean beaches, but huge outbreaks can pose a significant threat. “If you don’t remove them in just a couple of days, they start rotting, and they smell very bad,” says Hu. More specifically, they smell like rotten eggs, thanks to the hydrogen sulfide they release. (Not, thankfully, in enough density to combust the flammable gas.)

Rotting sargassum also attracts insects and bacteria, which makes it potentially dangerous to anyone walking on it with, say, an open cut on the foot. More importantly, perhaps, it also destroys the aesthetics of Caribbean beaches—aesthetics that, alongside tropical weather, have literally kept several economies alive. Tourism is by far the largest industry in most Caribbean nations and territories, including the Bahamas, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Turks and Caicos. (All of this comes on top of the complete disappearance of the 2020 tourism season due to COVID-19.) Ruin the beaches, and you ruin nations.

As a result, there have been increasingly desperate attempts to figure out how large the sargassum outbreaks will be, and to deal with the seaweed before it reaches the beaches. Prediction, Hu says, is still extremely limited to the short term. His models rely on tracking the movement of existing patches of sargassum farther out to sea. That means predictions can be accurate a few weeks to a few months out, but nobody can tell you what the situation will look like next year.

“People are not just concerned,” says Hu. “They’re seriously concerned. It’s not just the tourists: The local governments, they’re really concerned about their economies.” And that has led to extreme action in some cases. The Mexican navy has spent several million dollars building huge ships to keep sargassum away from its eastern beaches. In Florida, Miami-Dade County has brought in bulldozers and backhoes to pick up and remove the sargassum that washes up. Throughout the Caribbean, countries and territories spent an estimated $120 million in 2018 to fight the massive beaching of sargassum, according to Jamaica’s Minister of Tourism. Several companies have sprung up to sell sargassum booms—basically floating barriers designed to trap the sargassum offshore, so boats can head out and rake the stuff up for disposal.

All of these efforts deal only with the symptoms of sargassum outbreaks, not the cause. After all, sargassum was always out there and never really a problem until about a decade ago. The obvious question is, what happened? The answer, unfortunately, is elusive.

We know what you’re thinking. But climate change does not seem likely to be a direct culprit. Sargassum actually suffers when sea temperature rises. Warmer waters slow its growth and can actually kill it. “We don’t know what exactly is going on,” says Hu. “We have some speculation, but it’s better not to put too much speculation out there.” One of the possibilities—Hu is careful to say that this is just a possibility, with no proper, peer-reviewed studies to back it up—is what’s coming into the oceans.

Of the many rivers that feed into parts of the ocean that eventually become part of the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, the Amazon is the biggest. And there’s a lot more stuff in the Amazon than there used to be, thanks to vastly increased logging, agriculture, and ranching along the river. Waste products from those industries make their way into the river and eventually into the ocean. Those products aren’t necessarily toxic. In some cases, they’re basically or literally fertilizer. Theoretically, at least, organic material spread on a soybean farm in the Brazilian interior could be feeding sargassum growth, which then blows over and ruins a tourist season—and livelihoods—in the resort towns of Mexico.

The biggest issue raised by that theory, of course—in the way of all complex problems that connect disparate parts of the world, from climate to plastics to pandemics—is that there’s no end in sight.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook