The Greatest Banquet in Chinese History That Never Was

How grilled ape, braised bear paw, and steamed camel hump came to symbolize national unity.

A special menu is currently on offer at the Macau restaurant Fook Lam Moon. Highlights from the “Manchu-Han Imperial Feast” include sea cucumber, wild goose, pigeon egg, leg of water turtle, and bird’s nest soup. Rather than a modern gastronomic undertaking, the menu hearkens back to a legendary feast from Chinese history–one so magnificent, of such grandiose proportions, that it pacified sworn rivals and stabilized a nation. It was a feast for the ages. It was also a feast that probably never happened.

Instead, a misrepresented episode from Chinese history is today an enduring national symbol of ethnic harmony and reconciliation, reenacted time and time again in restaurants throughout the country.

The Qing Dynasty Emperor Kangxi (1654–1722) was no stranger to opulent dinner parties. He neutralized the Mongolian threat to China’s northern border early in his reign by holding a series of “Mongolian Vassal Banquets” in the Forbidden City, famously sending his princely guests home with leftovers. Later in life, he invited 3,000 of Beijing’s septuagenarians to his 61st birthday party for an event dubbed “The Feast of a Thousand Elders.”

When members of the Manchu ethnic group began taking over ministry positions long-held by the ethnic Han, tension gripped the country. As the story goes, Kangxi, himself a Manchu, turned to a proven solution: food. He planned his 66th birthday feast accordingly.

The three-day feast’s political effectiveness came from fusing two disparate cuisines. Northern Manchu fare was typified by communal “meat gatherings.” In one scene from the Unofficial History of the Qing Dynasty “anyone who shouted ‘more meat’ repeatedly would be greeted by immense gratitude” and “anyone who failed to finish at least one plate of meat would be met with contempt.”

Han cuisine, on the other hand, “prided itself on flavoring food with a wide range of staple ingredients and a great variety of condiments,” writes Dr. Isaac Yue, professor of Chinese studies at the University of Hong Kong in an email. As an example, he points to an excerpt from the famed novel Dream of the Red Chamber, where ten lines of text are dedicated to instructions on how to cook an eggplant.

Legend has it that no expense was spared in providing the attending rival ministers with a prodigious fusion feast. It seems no animal from land, sea, or sky was spared either, if a sample menu from an 18th-century reenactment “Comprehensive Manchu-Han Banquet” translated by Dr. Yue is to be believed.

An opening salvo featured soups of pork tendon and sea cucumber, crab and shark fin, and kelp and hog maw. Marquee dishes of the second course included braised bear paw with carp tongues, gorilla lips with rice dregs, “imitated leopard fetus” (“I have no idea what those were,” says Dr. Yue), and steamed camel hump. Another soup course featured one each of pig brain, soft-shelled turtle, and silkworm. The final meat course brought grilled ape, porridge-fed suckling pig, and minced pigeon, before a dessert of dried fruits cinched the feast.

Over the course of so many courses, it’s believed that the Manchu and Han ministers found it in themselves to bury the hatchet. Their settlement ushered in a period of peace throughout China, making the Manchu-Han Banquet the greatest in Chinese history. That the sample menu was dated to the reign of Kangxi’s successor shows that the banquet began spawning imitations almost immediately, as a potent symbol of reconciliation and unity.

To the fact-bound among us, however, the story is likely just that. “The romantic in me would love to believe that the desire for ethnic harmony was part of the reason for inventing such a feast,” says Dr. Yue. “But tried as I have, I’m unable to find evidence to back this up.”

Instead, extravagant banquets in the name of peace-making suited both newfound Chinese affluence and the political aims of the day. The overthrow of the Ming Dynasty in 1644 saw a period of reconstruction throughout the empire. “It took a few decades to recover from major war losses and food shortage,” notes Dr. Yue. The empire only found stability with the onset of food surpluses and the opening of trade routes in the early 1700s, right around the time of the mythical banquet. With ethnic reconciliation high on the list of imperial Qing priorities and Emperor Kangxi already owning a reputation for politically motivated feasts, the two phenomenon created the inspiring, if inaccurate tale of epicurean peacemaking.

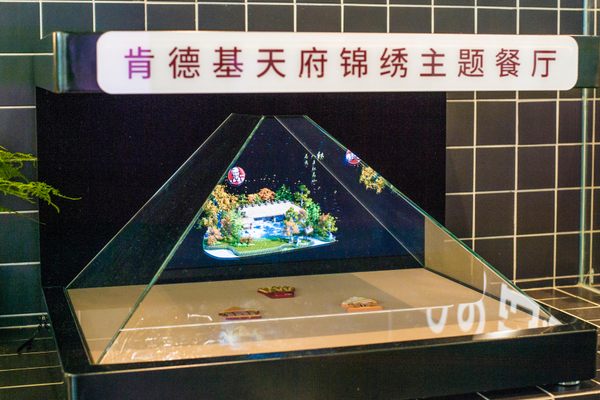

Facts (or lack thereof) aside, the ethos behind the legendary feast made its way into modern Chinese historical identity. A frequent reference in television and film, the episode became a point of national pride, akin to the United States’ celebration of Thanksgiving. A tradition has emerged among skilled jewelers of recreating standout dishes from the legendary banquet, carving bear paws, turtles, and fish from rare stones to be presented as a “feast” in mineral & gem shows. “The myth of ethnic harmony is what today’s society believes in,” says Dr. Yue. “So that’s what it means when the feast is evoked.” The very term Manhan Quanxi, or “Manchu-Han Banquet,” is now shorthand for any ostentatious meal or showy dinner gala.

Nor have gourmets ceased trying to recreate the fictive feast on tables across the country. Dr. Yue notes that after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, restaurants scrambled to hire chefs from the emperor’s kitchens who might reproduce an imperial banquet for their customers. The obsession became international in 1977, when the Tokyo Broadcast System commissioned a Hong Kong restaurant to recreate the feast over three months, with 160 chefs who created over 100 “original” dishes.

In 2010, Beijing restaurant Cui Yuan charged well-heeled customers $54,000 to indulge in 268 dishes over the course of a year for an “Imperial Feast” that included minced swan, deer’s lips, and peacock drumsticks. According to a press release, Fook Lam Moon’s feasts will run until the end of 2019, “encapsulating 5,000 years of Chinese history, drawing from the culinary traditions of China’s different ethnic groups.” All claim to have served the most authentic of recipes. Yet there was never an official menu to begin with, much less recipes.

The continually embraced falsification stands in for what, at this point, may as well have been an actual event. “Emperor Kangxi couldn’t have hoped for a better result in bringing peace and harmony to his people,” Dr. Yue says, “had he been the one to invent this feast as society now commonly believes!”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook