The Forgotten Chefs Who Made Carne con Chile a Texas Mexican Standard

“Chili queens” spread the dish from San Antonio’s plazas.

At sunset, the plazas of 19th-century San Antonio, Texas, would come alive with firelight and the songs of Tejano troubadours. There, industrious cooks supported their families by serving hot meals to the diverse crowds that congregated in the squares. These innovators, known as the “Chili Queens of San Antonio,” were forgotten for decades by the outside world. Yet they played a tremendous role in popularizing a standard of Texas Mexican cooking: carne con chile.

By the start of the Civil War, the descendants of pre-Hispanic Texans, Spanish settlers, and a host of other people had descended upon the city. According to the U.S. Census, San Antonio became home to more than 12,000 people by the 1870s. In his book A Journey Through Texas, Central Park architect Frederick Law Olmstead noted that a diverse crowd congregated in the shops and squares.

But for nearly a century, these enterprising chefs—who made chile and other delicacies—were central to both shaping and sustaining San Antonio nightlife. Graciela Sánchez, the director at San Antonio’s Esperanza Center for Peace and Justice, is a great-granddaughter of one of the plazas’ entrepreneurial women, Teresa Cantu. “She was a businesswoman,” she says. “They all were.” As with cities in Mexico and Spain, the plazas of San Antonio served as the centers for commerce and entertainment. “They were always alive,” says Sánchez. “That was where business was done during the day, with carts and shops. After that, people would read the news out loud, and others would sing. It was a place to socialize.”

Starting in the mid-1800s, local families would bring supplies from home and set up food stands, serving tamales, beans, coffee, and other home-cooked fare in the plaza. “They lived nearby in a community called Laredito,” says Sánchez. “They would walk over around four or five in the evening and work late into the night.”

The slow-simmered chile, with its careful combination of spices and distinct flavor, was one of their most well-known offerings, and was a mainstay in the plazas for over 100 years. For a dime, a patron could walk away with a full plate of chile, with beans and a tortilla on the side. “The food was comida casera, home cooking,” says food writer Adán Medrano. “It developed in that place for over 10,000 years. Each cook had their own recipes, and it was very much tied to family, culture, and region.”

Things took a turn in 1877, when the railroad service reached San Antonio. Upon arriving in the city, travelers from all around the United States would hear talk of the food stands, and the incredible fare locals served up there. Many came to test their palates with the cooks’ offerings, and the stands quickly became a crucial stop for anyone stepping off the train. In a 1927 issue of Frontier Times, Frank H. Bushick describes the surrounding plazas as melting pots. “Every class of people in every station of life…would line up along-side and eat side by side, unconscious or oblivious of the other.”

Individual offerings varied from table to table, and competing chefs served tamales, mole, or one of a hundred other specialties. In turn, the culinary trail blazers preparing these dishes were critical to fueling the late-night activity in San Antonio’s plazas for decades. They fed hungry crowds while merchants sold their wares and troubadours performed in the plazas. Tejano musicians, such as Lydia Mendoza, began their careers playing to the plaza’s patrons, too.

Women cooking these meals often drew from their own family recipes, and sold the dishes as an additional source of income. For many, it also became a way for them to defy the norm. “They were working to make a living,” says Sánchez. “During the day, some washed clothes or worked as midwives or healers. Some women, like my grandmother, were able to hire others to help them at the stands. Back then, women were not really allowed access to the streets, so this was a unique opportunity.”

But as word spread of these sensational dishes, tourists and writers alike objectified these culinary innovators, too. “Eroticizing them was the writers’ impression,” says Medrano. “The papers never referred to them as chefs or discussed any variation in their cooking.” By the 1920s, they were referred to as “chili queens,” which relegated their identity to a dish they made. “They didn’t call themselves ‘chili queens,’” says Sánchez. “That’s a name someone else gave them and it stuck.” It’s likely that the name of this dish, “carne con chile,” became Anglicized around this time, too. As Medrano writes, “they served a wide array of indigenous food: enchiladas, tamales, tortillas and carne con chile. All these dishes used chiles as the predominant flavoring but it seems that “chili” was easier for the newly-arrived to pronounce, so it stuck as the popular term.”

By the turn of the century, carne con chile had reached cities across the country. Tourists returned home craving more of the dish, and chile parlors sprang up with their own takes on it. “Depending on where you went, you would get something completely different than the ways it was made it Texas,” says Medrano. “In Cincinnati, it was more like spaghetti.” The chile served under the open skies of San Antonio was also markedly different than many modern recipes, too. Tomato was absent from the concoction, and beans were served alongside it instead of being cooked into the stew.

Although they fueled commerce in the city squares, authorities increasingly displaced these businesswomen. “The place became more bureaucratic, and the city looked at the open-air stands as an eyesore,” says Medrano. In the 1880s, construction of a new city hall and other development pushed these chefs out of the bustling plazas, and they temporarily shifted operations to the west side of town.

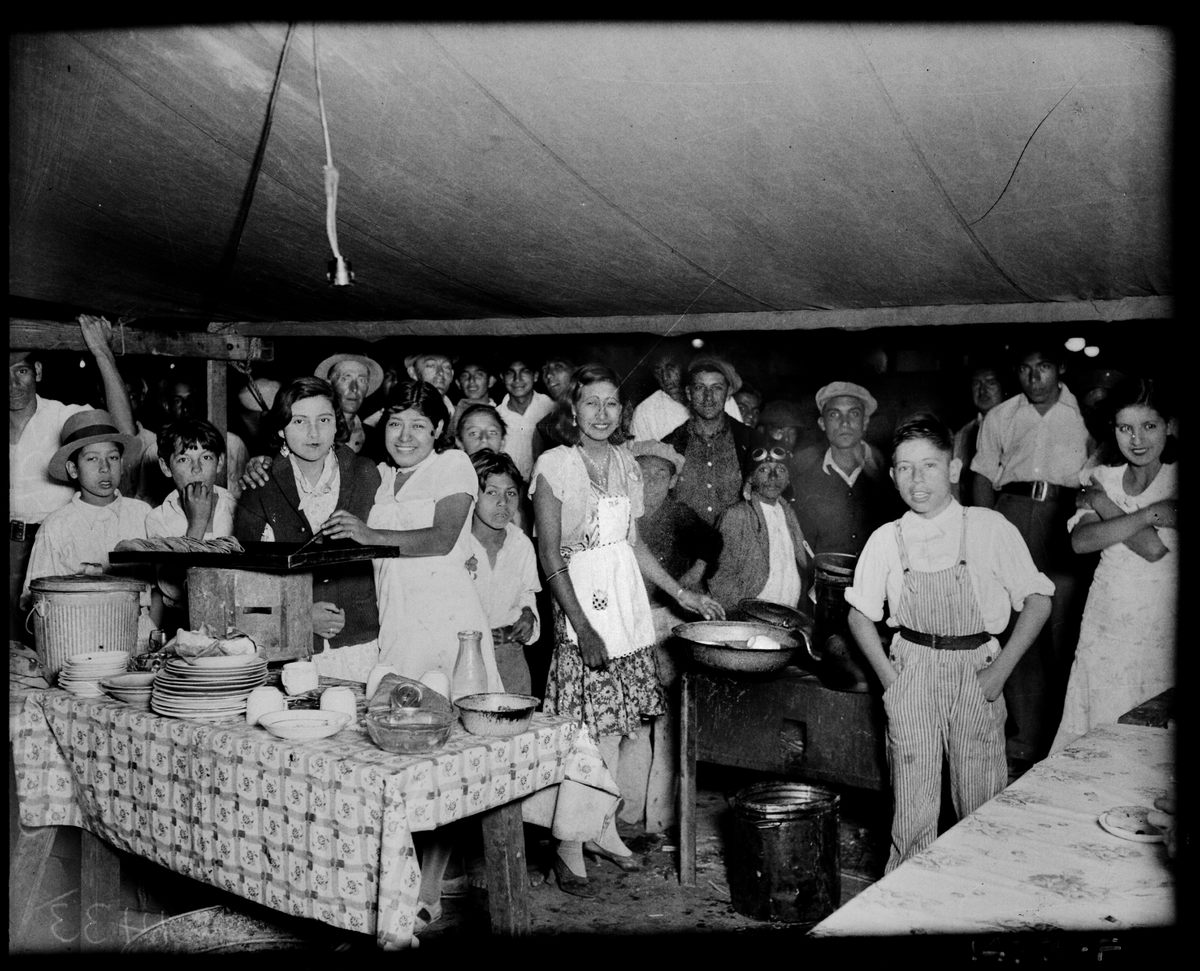

Authorities took it a step further in the 1930s, when the city health department ordered that the chefs enclose their operations in tents and mesh fencing. Some cooks continued under these confining conditions and close scrutiny of the health department, but in early 1940s, the last of the stands shut down. When the food stands disappeared, the women who made Texas Mexican staples, and helped popularize them, gradually faded from mainstream culinary history as well. “The agency and creativity of these chefs was erased,” says Medrano.

For generations, the legacy of the San Antonio entrepreneurs lived on in the kitchens of their descendants. “We never stopped cooking our food at home,” says Sánchez. But in recent years, chefs have introduced their family recipes to the public through restaurants, cookbooks, and food writing. “Now we have Texas chefs like Sylvia Casares, Johnny Hernandez, and others who emphasize family traditions and keep the food connected to the culture,” says Medrano. “They’re part of a resurgence of casera cooking in their own cities.” Medrano’s own cookbook, Truly Texas Mexican: A Native Culinary History in Recipes, records indigenous Texas dishes while exploring the centuries of tradition and techniques behind them.

For these chefs—and the many others who treasure these recipes—the tradition, aroma, and flavor of this food alike represents much more than daily nourishment. “The practice of cooking has served as resistance and memory,” says Medrano. “Every time we cook this food that was uniquely ours, we sustain our cohesion and identity.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook