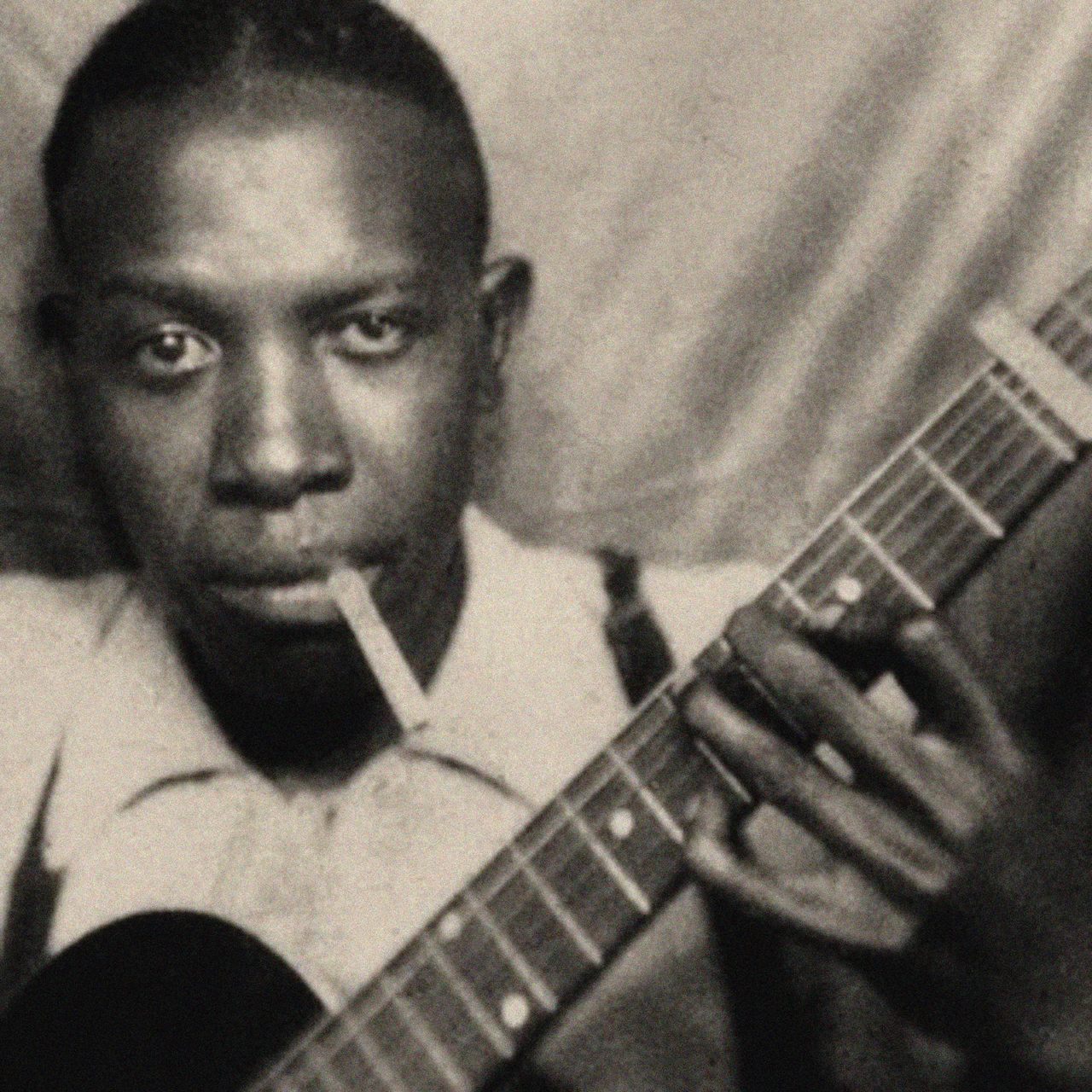

The Not-So-Mysterious Missing Grave of Blues Legend Robert Johnson

The supernatural has surrounded the guitar virtuoso for decades.

For blues fans around the world, the name Robert Johnson has grown synonymous with mystery, even sorcery. Throughout his short life, he moved around between Mississippi, Arkansas, and Tennessee, and didn’t leave much of a trail. His entire body of recorded work consists of just 29 songs (plus 13 alternate takes), recorded during two sessions in Texas. Those songs, however, include some of the most canonical in all the blues—such as “Sweet Home Chicago,” “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom,” and, of course, “Cross Road Blues.”

For more than half a century, fans and researchers have rhapsodized and hypothesized about Johnson’s itinerant lifestyle, untimely death, and iconic songbook. The mythology that swirls around this one man from Hazlehurst, Mississippi, has created its own “cottage industry” of publishing and tourism, says Bruce Conforth, coauthor with Gayle Dean Wardlow of the new biography Up Jumped the Devil: The Real Life of Robert Johnson. As Johnson’s life story seems more elusive, his place in blues history seems more secure.

The most famous myth surrounding Johnson concerns his alleged “deal with the Devil” at a Mississippi crossroads, where it’s said he traded his soul for guitar virtuosity. The Devil legend entered popular consciousness in the 1960s (long after Johnson died, in 1938), and is in many ways the wellspring of rock ‘n’ roll’s satanic motifs—from the Rolling Stones through Iron Maiden and beyond. The story’s obviously not true, but that’s hardly the point. The point is that the Devil is in rock music’s DNA, and the stories around Johnson helped put it there.

Steven Johnson, Robert’s grandson and vice president of the Robert Johnson Blues Foundation, says he first became aware of some of his grandfather’s mythology when he was a teenager. He found the stories neither scary nor particularly alluring, but he always felt, he says, that they were concealing or misleading, “that there was truth that hadn’t been told.”

Some decades later, a new yarn was spun—not about Johnson’s life, but his afterlife. No one seemed to know exactly where his mortal remains were buried, and the idea took hold that there were at least three possible gravesites. Though the actual mystery has been cleared up over the years, the myth rolls on. The New York Times boosted it in September 2019, the National Park Service still provides an outdated account, and the rumor continues to travel easily among tourists and blues pilgrims. It just seems to fit: Robert Johnson, that perfectly unknowable spirit of the blues, can’t find eternal rest.

Whatever Robert Johnson’s life lacked in actual magic, it certainly made up for in pure human drama. According to Up Jumped the Devil, Johnson died from poisoning. He was having an affair with Beatrice Davis, a married woman whose jealous husband, Ralph, dosed Johnson’s whiskey with naphthalin—likely without the intention to kill. (The drug was commonly used to subdue rowdy patrons at bars.) What Ralph didn’t know was that Johnson had recently been diagnosed with an ulcer, and the spiked drink proved too much for him in his weakened state. As with all things Johnson, it’s not so simple, since his death certificate names syphilis as the cause of death. Conforth and Wardlow think it’s likelier that the disease was listed to obscure the foul play.

That death certificate—discovered by Wardlow in 1968—states that Johnson was buried at “Zion Church” in Leflore County, Mississippi. But it provides no more information than that, and actually just raises more questions. Was it Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Morgan City, Mississippi? Little Zion Church in Greenwood? The other Mt. Zion Church, which is also in Greenwood? Leflore County is small, but there was a world of possibilities within it—any one of those places, or somewhere else entirely. For decades, the true gravesite was an open question, with scattered anecdotes in place of answers. All that anyone knew for sure was that Johnson was buried in an unmarked grave—just like most African Americans from his region and era.

Things stayed that way until 1991, more than 50 years after Johnson’s death. In April of that year, Morgan City’s Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist (MB) Church dedicated the first big Johnson memorial, arranged by the Mount Zion Memorial Fund (MZMF). The organization aims to preserve historic black churches by erecting memorials to blues musicians—whose remains may or may not lie in unmarked graves at those churches—and Mt. Zion MB could make as fair a case as any. Conveniently, the church is located just off of Highway 7, so its memorial can winkingly quote Johnson’s “Me and the Devil Blues,” in which he sang, “You may bury my body / Down by the highway side.”

While it didn’t amount to actual evidence, that song had helped fuel some of the speculation over Johnson’s burial site. So did the liner notes to 1990’s Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings, released by Columbia Records, which suggested that Johnson was buried at Mt. Zion MB. Actual documentation, however, had not been gathered beyond that ambiguous death certificate, and MZMF understood that. T. DeWayne Moore—currently MZMF’s Executive Director, and a visiting historian at Bowling Green State University in Ohio—diplomatically notes that MZMF never claimed to be marking Johnson’s actual gravesite. The memorial is not a headstone, he says, but a cenotaph, or a monument to someone whose remains have not been located.

Moore is frank about what MZMF was hoping to achieve: The organization “leveraged the possibility that [Johnson] might have been buried there” in order to save the church from imminent foreclosure. MZMF’s memorials, he says, are “tools to save the cemeteries and make sure they’re not eradicated, because they’re some of the last elements of cultural heritage that are left to the landscape.” The Johnson memorial got the job done. Mt. Zion MB, and its obelisk commemorating the musician, are still standing—even if Johnson is actually buried elsewhere.

Just two months before that dedication, however, a smaller stone had been set in his honor in the nearby town of Quito, also in Leflore County, outside the Payne Chapel Missionary Baptist Church. Atlanta-based band the Tombstones had sponsored this one, in tribute to one of their musical heroes. This stone does indeed claim to mark Johnson’s grave, on strength of testimony from a woman known as Queen Elizabeth Thomas. A self-identified ex-girlfriend of Johnson’s, Thomas told Living Blues magazine in 1990 that Johnson had been buried at Payne. However sincere Thomas’s testimony may have been, the evidence was always scant—considering, especially, that the death certificate named a “Zion Church.” But for all intents and purposes, Johnson basically now had two memorials resembling grave markers within two miles of each other.

All along, it was just as likely—if not more so—that Johnson was buried elsewhere. Back in the late 1980s, blues researcher and folklorist Mack McCormick located Johnson’s half-sister, Carrie Spencer Harris, who had been living in Memphis at the time of Johnson’s death. Harris told McCormick that, upon learning that Johnson had been hastily buried in a homemade casket, she hired the only black undertaker in the area to reinter Johnson in a higher-quality coffin. And that undertaker, Paul McDonald, kept records.

While rumors of the reinterment prompted speculation that Johnson’s body may have been moved from one cemetery to another, McDonald’s records said otherwise. Verified by McCormick and later by Conforth, the documentation stated clearly that Johnson was buried at Little Zion Baptist Church, off of Money Road in Greenwood. Further corroboration came in 2000 from a Rosie Eskridge, whose husband Tom had dug Johnson’s grave. Eskridge not only identified Little Zion as the burial site; crucially, she also verified the identity of one Jim Moore, who had been listed as the informant on the death certificate, and confirmed the reports of a homemade casket.

Wardlow, the co-biographer and a self-appointed “blues detective,” began his search for Robert Johnson’s death certificate in 1965. From that point, it took him nearly 40 years—with the work of many other researchers and witnesses—to reach a confident conclusion regarding Johnson’s gravesite. Once Eskridge came forward, however, the case seemed pretty decisively closed. Even T. DeWayne Moore, whose MZMF arranged the Johnson cenotaph at a different church, concurs. “As far as I’m concerned,” he says, Little Zion is “where the guy is buried.” Johnson’s headstone at that church has been in place since 2002, and a sign on the Mississippi Blues Trail acknowledges that Johnson “is thought to be buried in this graveyard.”

Yet confusion appears to have lingered. Up Jumped the Devil—which unequivocally maintains that Little Zion is Johnson’s burial site on strength of the accumulated evidence—was only published in June 2019, but much of this information has been publicly available for decades.

“There’s nothing mysterious about” an unconfirmed gravesite in the Mississippi Delta, says Elijah Wald, author of Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. Wald emphasizes that many of Johnson’s neighbors and contemporaries—black, rural Mississippians just a few generations removed from slavery—are also buried in unmarked graves. “That’s about poverty and racism,” not mystery, he says. What distinguishes Robert Johnson “is that a bunch of white people care where he’s buried.”

Johnson’s legend truly began to grow after 1961, when Columbia Records released King of the Delta Blues Singers, a compilation of the still-relatively-obscure bluesman’s recordings. The album was met with particular enthusiasm in England, where interest in American folk and blues music had been growing since the end of World War II. Among the young English people who took to Johnson’s music were guitarists named Keith Richards and Eric Clapton, whose bands—among many others—would go on to cover Johnson and educate the whole world of his tremendous influence. (Bruce Conforth, fittingly, was also founding curator of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.)

In his 2007 memoir, Clapton wrote that he “had found the master” upon hearing King of the Delta Blues Singers. Steven Johnson, the musician’s grandson, recalls a similar exchange he had with Clapton, who said that Robert’s playing simulated the sound of three guitars with just one. “I cannot do it,” Clapton told him. “I tried it. I can’t.”

Thanks to the satanic flirtations of bands such as the Rolling Stones (and some sketchy documentation), Johnson’s crossroads legend quickly gained international renown as one of rock ‘n’ roll’s mythological pillars. It gave the white audience something it craved, says Wald: the image of the “dark, scary, devilish Delta, which was much more interesting than coming from London or New York.” Over time, the more zealous fans would ask enough questions and generate enough rumors to bring about three neighboring memorials.

This darkly romanticized image of the Delta has, of course, brought tourist dollars to the region and inspired some of the world’s most recognizable rock music. But it also propagates a host of old injustices. It’s racist towards Johnson, who didn’t need the devil’s help to master the guitar. “He just learned how to play the guitar after many years of practice,” says Michael Johnson, another of his grandsons and treasurer of the Robert Johnson Blues Foundation. (Admittedly, some of that practice, with his mentor Ike Zimmerman, took place in a cemetery, likely because it was quiet.) It obscures other musicians whose contributions to the genre were similarly powerful, if perhaps less marketable. Howlin’ Wolf, for example, was actually born before Johnson—but because Wolf lived longer, he’s sometimes considered a follower of Johnson’s rather than a contemporary.

To the African Americans who created it, blues was not necessarily “dark, scary, devilish music,” says Wald. Instead, it “was a completely present style,” nuanced, dynamic, even joyful and funny. This became clearer to Wald, who is also a musician, when he traveled to Leflore County to perform at the dedication of the Mount Zion MB cenotaph. The church’s pastor, Reverend James Ratliff, was one of many locals who had first heard of Johnson because of the plans for the memorial.

For Steven Johnson, the stakes are ultimately personal. “That’s my heritage,” he says, “that’s my bloodline. You want the truth to be known.” At the same time, neither Johnson, Conforth, nor Wald wants to see any of the memorials removed. Johnson appreciates that his grandfather’s fans enjoy the mystery. He just wants that mystery—and the history—to be fully understood.

Conforth, likewise, wants to bring flesh and blood back to the ghost story. Explaining his desire to write a myth-busting biography, Conforth says he “wanted Robert to become, or at least try to become, the real person that he actually was, and not the myth that all these people have made him into.” Wardlow concurs, with a point that shouldn’t really need stating.

“The man,” he says, “was a human.”

You can join the conversation about this and other Spirits Week stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook