The Struggling Vineyards That Helped Inspire Karl Marx’s Communism

Boozed-up intellectuals of the world, unite.

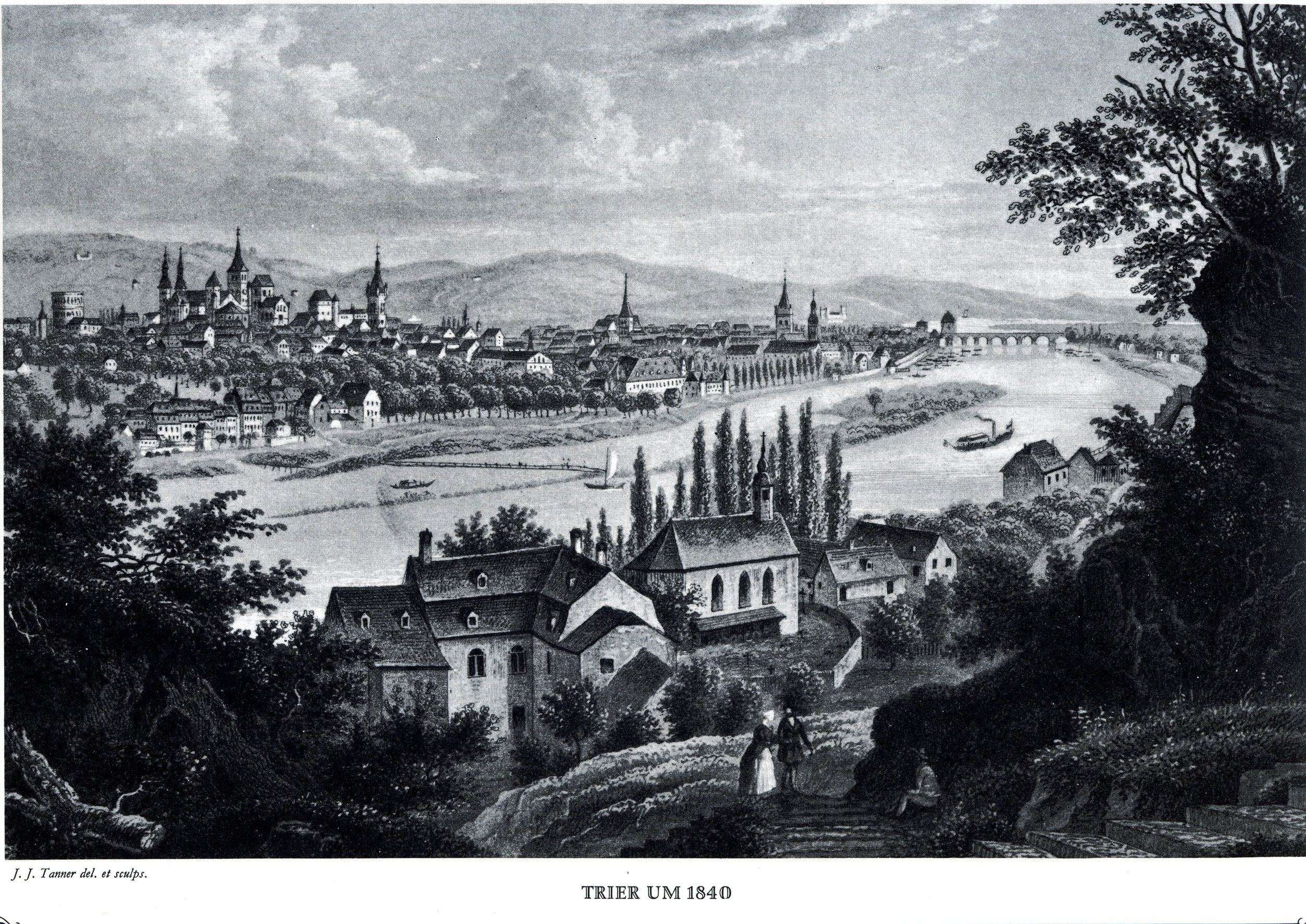

A spectre is haunting Trier, Germany—the spectre of Karl Marx. Today, tourists to the small Rhineland city visit the house where Marx was born and gaze at the armchair he died in. They take selfies in front of a larger-than-life Marx statue, gifted to the city in 2018 by the Chinese government. And if they want a more embodied experience of the revolutionary, who spent the first two decades of his life in Trier, the official tourism outfit offers several guided costume tours, says Dr. Paula Kolz, a historian and marketer at the agency. Visitors can opt to learn about the city from a period-era nightwatchman or Marx’s wife, editor, and fellow revolutionary, Jenny von Westphalen.

While Trier officials don’t have precise figures on how many tourists come specifically for Karl Marx-related attractions, Kolz says that 160,000 visitors attended Marx’s 200th birthday exhibition in 2018. In the same year, 60,000 tourists visited the Marx House, which is now a museum, according to Margret Dietzen, a Museum Educator. Visitors come from all over the world, the two officials say, but there’s a particularly robust Chinese tourism market, ostensibly from groups seeking a connection to Communist history.

One aspect of Trier’s tourism seems unassociated with Marx: the region’s wine industry. The rolling hills of the nearby Mosel River Valley are striated with rows of orderly arbors. But these small vineyards, now known for their fruity white wines, played a larger role in the history of leftist thought than their quaint appearance might suggest. In the early 1840s, the economic struggles of these very vineyards inspired Marx to criticize the draconian Prussian government—and in the process, some historians argue, begin developing the theory of historical materialism for which he is best known.

“It’s the first time he had cared about economic questions at all,” says Jens Baumeister, a Trier tour guide and author who describes himself as “an art historian, archaeologist, wine lecturer, and Marx lecturer.” In 2018, Baumeister published a book whose title features an even bolder claim: How Wine Made Karl Marx a Communist.

In his student days, though, Marx was more interested in drinking wine than in writing about the economics of it. Son of a bourgeois Jewish family that had converted to Chistianity in accordance with the reigning Prussian religion, Marx grew up at a time when wine was a staple beverage, not considered alcohol the way liquor was. Like many of their wealthy contemporaries, who acquired land as an investment and to stock their own cellars, the Marxes owned part of a vineyard. When 17-year-old Marx moved to Bonn as a college student in 1835, he brought these boozy proclivities with him.

“The idea that he was president of the college drinking club is just a legend,” says Baumeister. But it’s an oft-repeated one, and it has some basis. Marx and his friends “spent their time in Bonn’s taverns, drinking heavily, and then brawling with other students,” writes Jonathan Sperber in his biography of Marx. Marx’s drinking inspired letters of consternation from his father, who disparaged his “wild rampaging.”

Yet Marx’s “rampaging” reflected a deeper divide in German politics. The brawls resulted from tensions between mostly untitled, bourgeois students from Trier, who were discontent with Prussian rule, and aristocratic students from eastern Prussia, who were more supportive of the government. When Marx finished his studies and moved to Cologne, some 100 miles north of his native Trier, he turned his attention toward these political and economic issues. This time, however, they were expressed not in wine drinking, but in wine growing. The Mosel Valley vintners were in crisis.

It was a long time in the making. When the Prussians regained control of Germany from Napoleon in 1815, they implemented policies favorable to the winemakers. They imposed tariffs that protected Mosel winemakers from outside competition. That, combined with several good growing years in the early-19th century, meant that by the 1820s, Mosel’s winemakers were on their way up. But according to Sperber, in the 1830s, the Prussians did an about-face, abruptly opening the market. Winemakers who had invested in equipment, growth, and property with the expectation of a protected market found themselves facing uncertainty, and falling prices hit smaller growers especially hard. By the time Marx moved to Cologne in 1842, there was still no relief in sight.

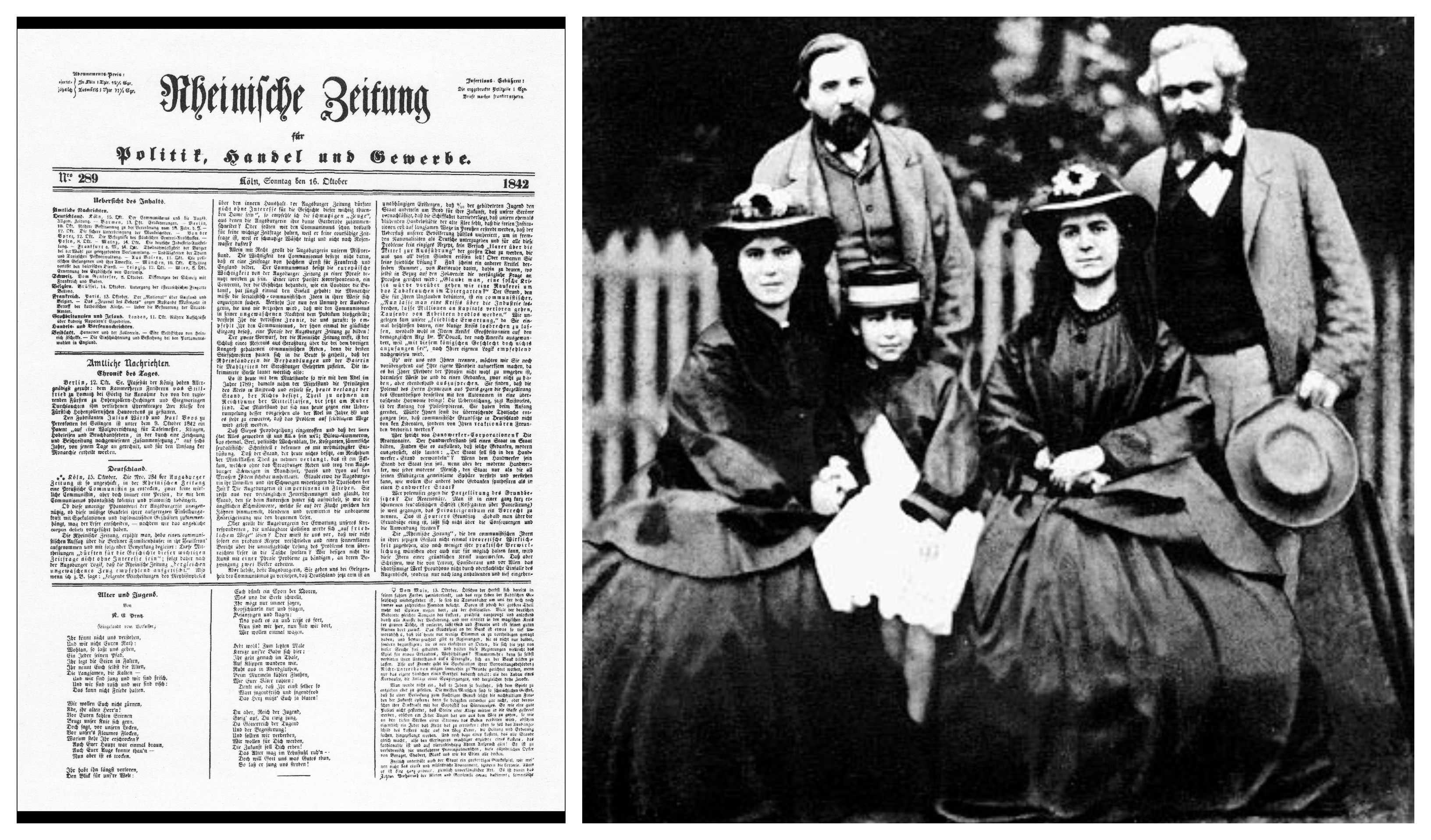

While still a devoted drinker, Marx had also become a serious student, a devoted Hegelian who saw history as a forward march propelled by conflict between opposing ideological forces. In 1842, Marx joined a newly established, liberal-leaning newspaper, the Rheinische Zeitung, as editor. Inspired by the influence of French socialism and the dire economic straits of the Mosel vintners, he began publishing articles critical of the Prussian government.

“For a long time the desperate state of the vine-growers was doubted in higher quarters, and their cry of distress was regarded as an insolent shrieking,” wrote Marx. “The ruin of the poorer vine-growers is regarded [by Prussian authorities] as a kind of natural phenomenon, to which one must be resigned in advance, seeking only to mitigate the inevitable.” But, Marx went on, the struggles of the growers were not natural or inevitable: They were a direct result of material conditions and Prussian policies, and they could be changed. Friedrich Engels, a wealthy industrialist and Marx’s co-writer, co-revolutionary, and, by all accounts, best friend, summed up the effects of the episode on Marx’s thinking simply: Through his writing on the Mosel wine growers, Engels wrote, Marx “was led from pure politics to economic relationships and so to socialism.”

It also made him an outlaw. The Prussian government, notorious for its deep-seated aversion to criticism and its terrifyingly efficient army, was enraged by Marx’s criticism. In March 1843, they shut down the Rheinische Zeitung entirely. The same year, Marx fled to Paris, inaugurating a pattern of repeated exile that would follow Marx across Europe for decades. Marx and Jenny von Westphalen moved to Paris and eventually to London, where he would author Capital.

Marx’s political and financial woes did not, however, dampen his drinking. Wilhelm Liebknecht, a German socialist and contemporary of Marx and Engels, recalls an evening in London when Marx and an intellectual compatriot went on what can only be described as a bender. They drank “in every saloon between Oxford Street and Hampstead Road,” smashed several street lamps, and narrowly avoided the police.

Marx’s personal habits were similarly free-spirited. “He leads the existence of a real Bohemian intellectual,” wrote a Prussian intelligence agent who had been assigned to trail Marx. “Washing, grooming, and changing his linen are things he does rarely, and he likes to get drunk.” Of course, says Baumeister, besmirching Marx’s reputation was the agent’s job. But decades of correspondence between Marx, Engels, and Marx’s wife, Jenny, in which he thanked Engels for sending the impoverished family wine or requested more, verify at least the last section of the spy’s report. Sometimes, Marx and Engel’s zest for pleasure and politics came together. When asked by an English pollster in 1865 what his idea of happiness was, Engels replied, “Chateau Margaux 1848.” 1848 was the year revolutions swept Europe. It was also a great year for French wine.

A century and a half later, Trier’s residents continue to benefit from tourists’ interest in Marx’s legacy, even while some locals have reservations about celebrating the revolutionary. When the People’s Republic of China gifted the city its Marx statue last year, protestors leery of the government’s long record of human rights abuse demonstrated against its installation. With Cold War trauma running deep in Germany, says Kolz, “We have a very stiff relationship to Karl Marx.” Still, says Margret Dietzen of Karl Marx House, the past few years have seen an uptick in visits to the museum, part of what she calls a “a Marx renaissance” in response to the 2008 financial crisis.

The vintners of Germany’s Mosel Valley remain mostly small-scale, noted for their lemony Rieslings and agrotourism. At least one of these local vintners, however, remembers the wine-lover who went to bat for their industry. In 2008, Erben von Beulwitz Spätburgunder, a small vineyard nearby the erstwhile Marx winery, produced a Karl Marx Pinot Noir—a capitalist enterprise, to be sure, but one the booze-loving revolutionary would likely have appreciated.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook