How Museums Make Their Fake Foods Using Real Recipes

At Colonial Williamsburg, creating historic food scenes is a team sport.

The morning daylight streams in through a wavy glass windowpane to illuminate a table full of food: There is a platter of grilled fish surrounded by lemons, little meat pies arranged on a plate, a bowl of fruit, and even a small pitcher full of frothy punch. Laid out with cutlery and dinnerware, it looks ready to welcome guests, or perhaps a family that is about to gather at the table.

Except that it’s not. Each of these pieces of food is fake. The fake fish, the fake meat pies, and even the fake fruit were carefully placed by curators at Colonial Williamsburg who, like their peers at other historic houses turned museums, aim to present a lifelike and historically accurate experience. The painstaking research, cooking, and molding behind each “faux food” is a little-known industry within the museum world.

“Food brings the room to life, helps make the house a home,” says Amanda Keller, Associate Curator of Historic Interiors and Household Accessories at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (CWF).

For most of American house museum history, staff cooked or gathered real food to lay out on tables and hearths. In England and Australia, this is still common, but in the United States, especially in warm, humid areas, spoilage and pests have always been a problem. Additionally, in the U.S., conservation concerns raised in the 1980s led curators to shy away from placing foods that can rot or spill on or around what are often period antiques, original flooring, or brick work. (Cooking was often done right on the historic hearth.)

Similar concerns keep curators from buying faux food from the most famous purveyors: Japan’s fake-food manufacturers. The $90 million industry rose in popularity after World War II as a way to help Americans identify and choose dishes on Japanese restaurant menus. While these pieces are beautiful and life-like, Keller explains that “we really have to take into consideration ‘off-gassing’ from objects, something which can degrade our artifacts. In fact, even bringing fresh flowers into an 18th-century dwelling can really affect it. There is a lot to consider when staging a historic structure.”

As a result, museums began constructing their own historically accurate faux food creations. And as is the case in many aspects of American historical conservation, reconstruction, and research, Colonial Williamsburg has led the way. Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia. Once the state capital, the historic district was founded in 1699, and the historical faux food work at the attraction—a site that encompasses multiple buildings in a historic, 173-acre area—is a collaboration between chefs, craftspeople, and curators.

Each project is a new challenge, and Keller’s current project is a cake for an 18th-century wedding scene. Today’s tiered, white-on-white cakes were a later invention, so Keller looked to historic cookbooks (her favorites include The Art Of Cookery by John Thacker and The British Housewife Companion by Mrs. Martha Bradley), engravings and drawings from the time, and even historic letters, which is where she discovered a detailed description of a wedding cake written by a wedding guest to a friend. She cross-referenced all these findings with a drawing of Twelfth Night cakes from the period.

“From there, I rely heavily on the Historic Foodways department,” Keller explains. The department uses 18th-century equipment and methods to interpret and replicate foods, which in this case includes historic cake pans and baking the cake over a wood fire.

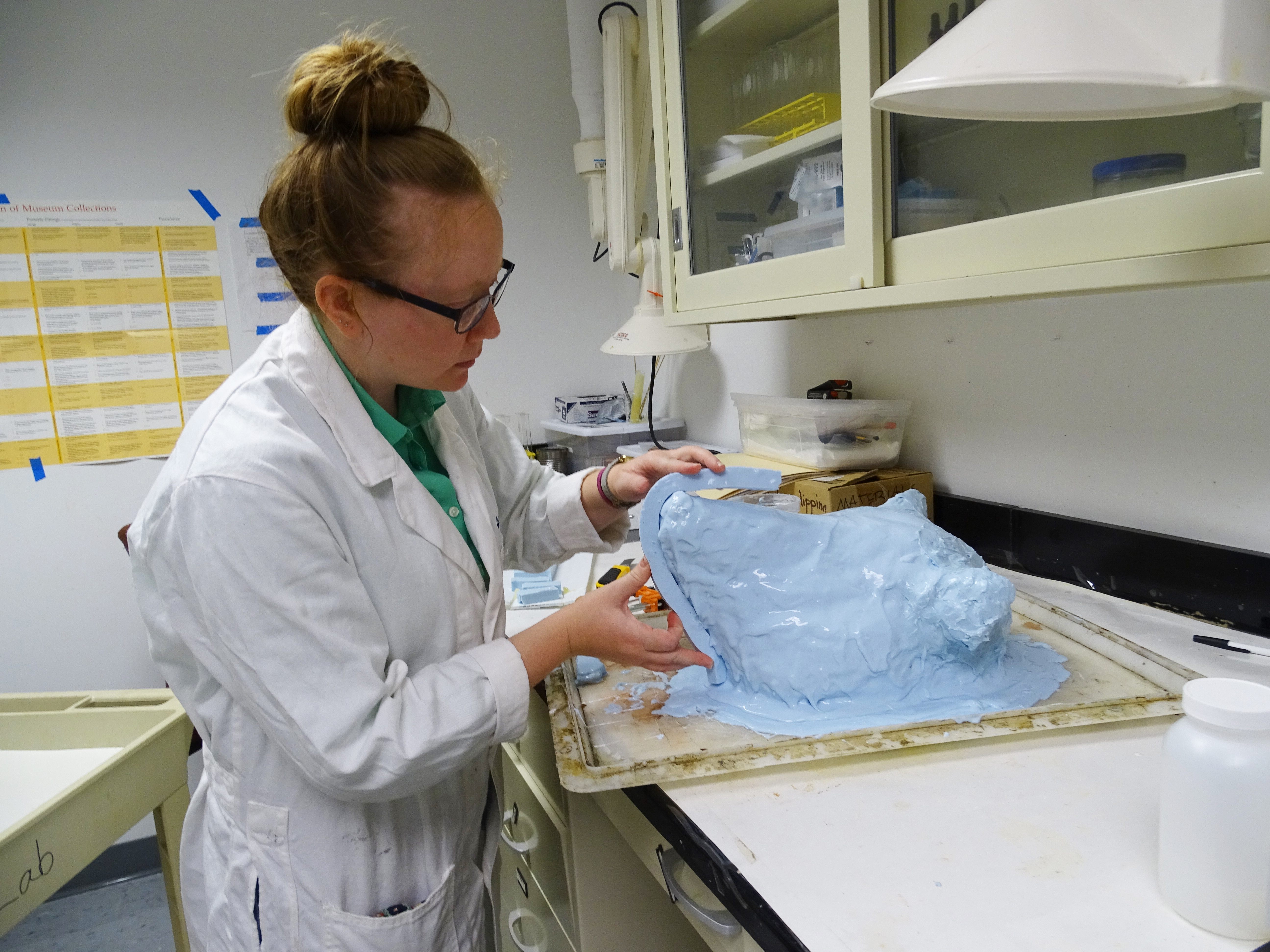

The next step is for Jennifer Thornton, Senior Conservation Technician, to actually recreate the cake. She’ll begin by taking photos of the cake created by the cooking team, which will look much simpler than modern cakes, but involve royal icing, a frosting still in use, but usually not for wedding cakes. “If I can mold it, I will,” Thornton says. “Every material we use goes through a testing process, and to really adhere to preventative conservation—avoiding problems before they start—we have to make stuff on our own.”

“She never gets intimidated by any new project,” Keller says admiringly. If molding won’t work, or if something is too big or too bulky, then Thornton might build an item out of plaster and use non-toxic paint to creatively recreate patina, such as the colors of a grilled fish versus a fresh caught one, or in the cake project, the texture and crumb of a cake that was baked in a lidded mold nestled among the coals of a wood fire. Once the cake is ready, Keller and the curators will design the table settings.

CWF constructs around 200 faux food objects a year, and staff draw from their faux food “prop closet” to switch out food displays to match the season (apples in the fall versus berry tarts in summer) and keep them “fresh” for interpreters and visitors, even though fresh means completely fake.

Not every museum and historic site has the resources to make their own faux food, and CWF is not permitted to sell their creations, so other craftspeople feed the need. Sandy Levins, of Historic Faux Foods in New Jersey, creates items ranging from raw calf tongue to Stargazy Pie (a pie with whole fish heads and tails sticking out of it that fascinated her so much she made one “for fun”).

Levins has recreated dishes from bygone eras for historic sites that include Monticello, Mount Vernon, and New York City’s Tenement Museum. She got her start while part of a historical society that wanted to use faux foods to take an 18th-century house from “stale and sterile” to more lively. Her mentor was Jane Ann Hornberger of the Winterthur Museum in Delaware, and once Levins created a “platter of raw oysters that actually looked juicy enough to slurp,” she remembers, she began her new work in earnest, collecting historic foodways reference material, using her home kitchen as a creation lab, and slowly building a reputation in the museum world for her accuracy and ability to provide full table and room settings.

Teresa Teixeira, current Curator of Historic Textiles at The Charleston Museum in South Carolina, is a newer player on the faux food scene. She got her start at CWF in the textiles department, and often spent time in the historic buildings when visitors weren’t there. “Audiences are really drawn in by clothing displays and food, and the faux foods at Colonial Williamsburg really drew me in, too,” she says.

When she began working at Montpelier, the historic site didn’t have a large budget for faux food or a staff to make it, so the team ordered a couple pieces from Levins. “We ordered the most difficult things, in this case two roasted chickens and some meat-stuffed cabbages, and I volunteered to try my hand at making the rest,” she says. Teixeira individually molded and painted a bowl full of peas and made a savory, herb-filled tansy cake. “[The peas] looked great, but I won’t do that again,” she says. “It took forever.”

These days, she runs a side faux food hustle out of her home garage. She always turns in a report of the research she does, as a way to help these smaller museums’ volunteer staffs. “It’s fun and rewarding,” she says, despite the fact that food occasionally rots in her garage as she waits for the mold to set.

These recreations of historic recipes—into non-edible objects—can often teach us about seasonality and regionality in foodways. As faux food creators delve deep into what would have been available and local, they can discover forgotten ingredients and recipes that speak to the place, when people had to make do with what they could forage, grow, hunt, or catch. Through that research, these craftspeople bring to life overlooked elements, in a way that doesn’t attract rats into the Monticello kitchen or harm the objects they’re showcasing. And their creations, which bring to life the past, can become works of contemporary art on their own.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook