The Life and Times of Brighty, the Grand Canyon’s Most Legendary Burro

He was a muse, a good luck charm, and the center of a controversy over invasive species.

For good luck, visitors to Grand Canyon National Park stroke the nose of a life-sized burro sculpture, its muzzle polished by thousands of hands. Like a dog on its haunches, the statue sits in the lobby of the Grand Canyon Lodge, built at the very edge of the Canyon’s 8,000-foot North Rim.

Few know the story of the real-life animal—Brighty—represented by the sculpture, much less that the burro inspired a 1950s children’s book, which was later adapted for the screen, with Jiggs the Donkey cast as Brighty the Burro (burro is the Spanish word for donkey).

Even fewer realize that the statue itself—commissioned by the film’s director and donated to the park—became the center of a bitter controversy over whether feral burros were a valuable part of Canyon history or invasive creatures who should be exterminated.

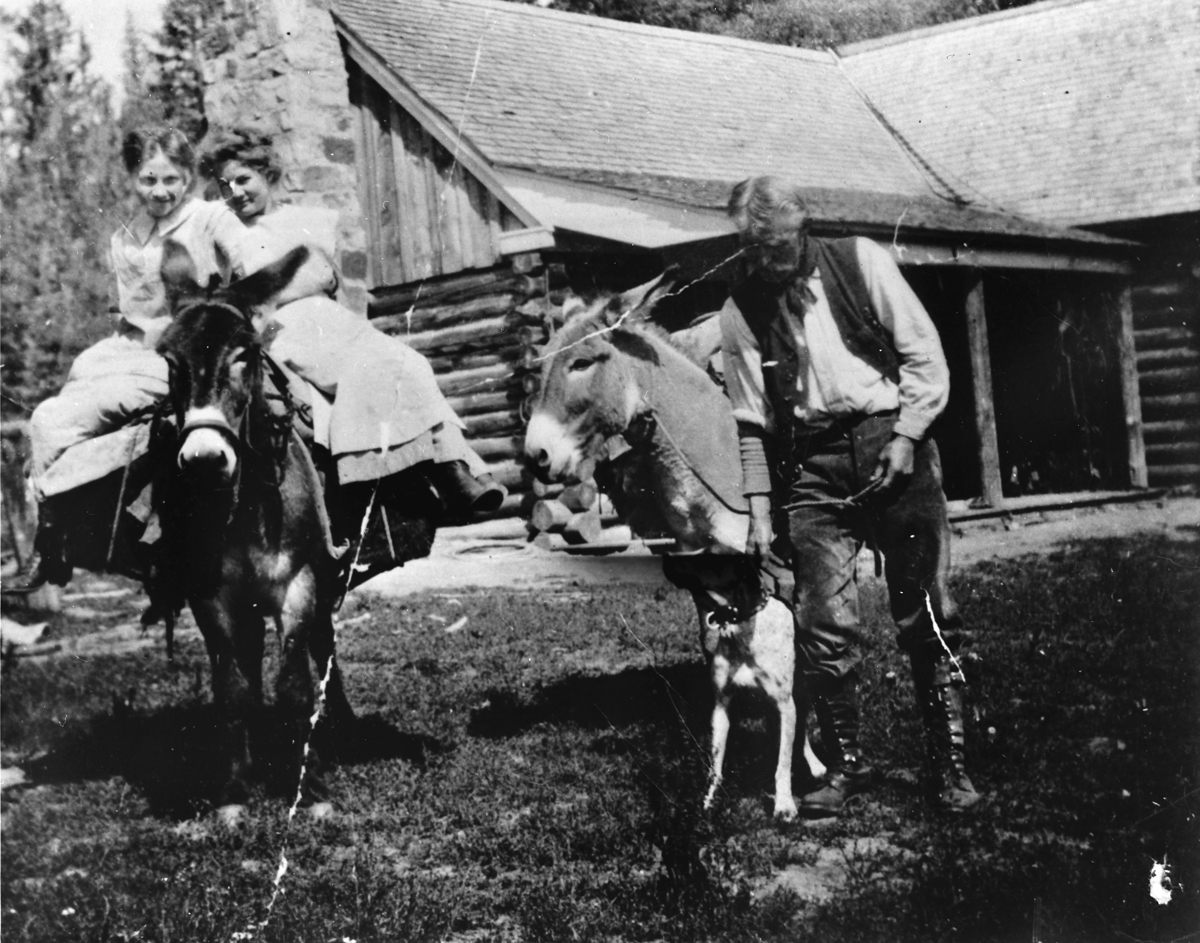

Native to Africa, burros were brought to the Americas in the 1500s by the Spanish. By the late 1800s, prospectors in the Canyon used them as beasts of burden, companions, and good luck charms— according to the professor John Wills in The Journal of Arizona History, folklore had it that a wandering burro would lead you to gold. If a miner gave up on the search for gold, copper, lead, or asbestos, however, he would abandon his burros along with his picks and pans. The equipment corroded; the burros turned feral and thrived.

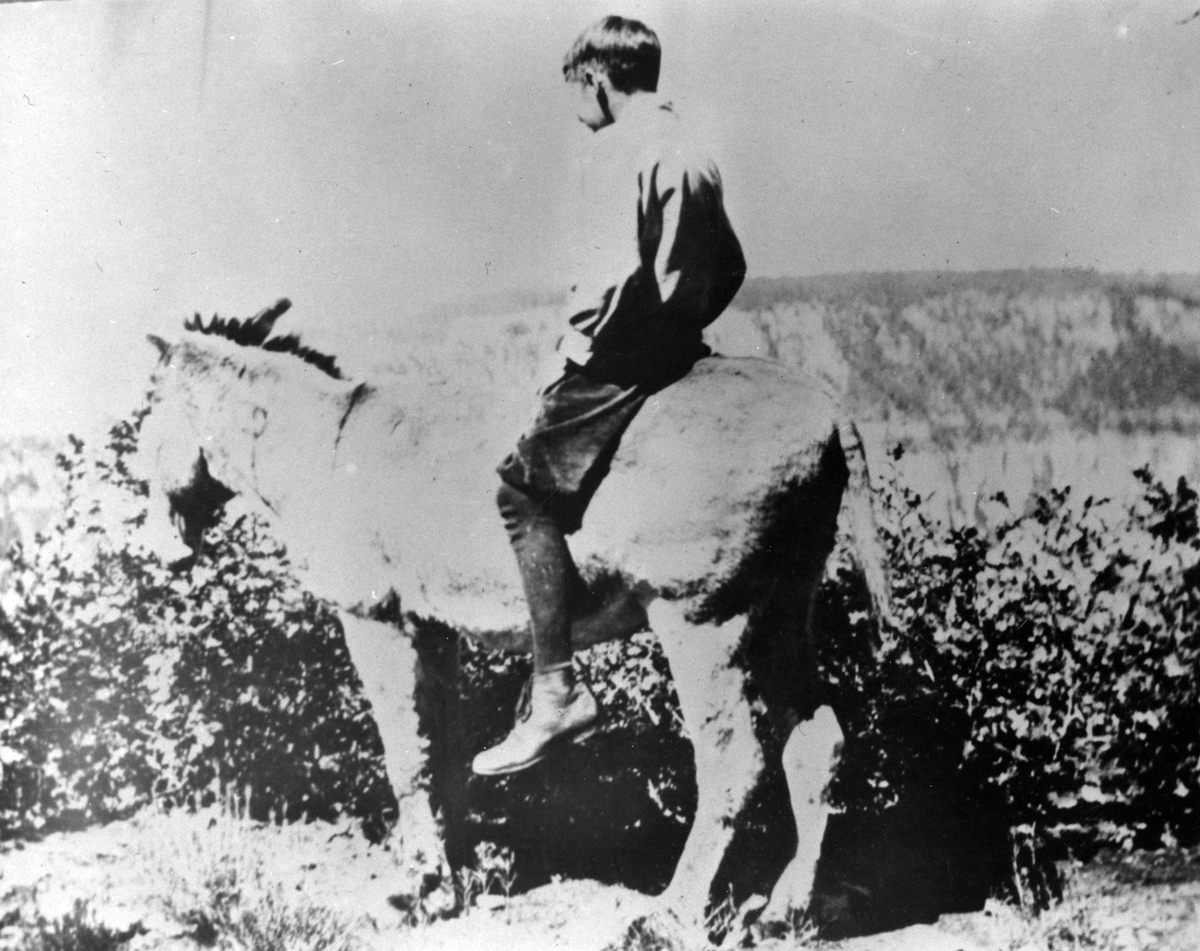

Brighty himself, who lived from about 1882 to 1922, was first seen in the Canyon near an abandoned miner’s tent, sitting vigil as if expecting the tent’s occupant to return. The burro appreciated occasional human companionship, especially when pancakes were involved. He spent summers on the cooler North Rim, hanging out with the game warden Jim Owens or the McKee family, who managed the first tourist facility on the North Rim, which opened in 1917. Brighty came and went as he pleased, toting water for the McKees’ young son, but scraping off any loads he deemed unworthy of his efforts. For instance, if a hunter caught Brighty and tried to make him pack his gear, Brighty would sneak away, rubbing the pack against trees until the lashing loosened and the load fell off.

It was along the North Rim that early Canyon tourists first met Brighty, probably between 1917 and 1922. Wills writes, “Vacationers struggling to interpret, or connect with, the immense scale of the Canyon (John Muir called it an ‘unearthly’ place), appreciated the presence of a familiar creature.”

But Brighty’s hybrid existence—not exactly wild, but not domesticated enough to be consistently useful—would count against him and his kind when the park service decided in the early 20th century that it should restore the Canyon to a pre-Columbian state of virgin splendor. Having arrived with the Spaniards, the burro was not native to Arizona.

Rather than relocating the animals, in 1924, shortly after Brighty’s death, rangers began hunting burros in earnest. According to Wills, between 1924 and 1931, they killed 1,467; records show that between 1932 and 1965, rangers shot 370 more.

The hunts went on with little public knowledge, until a 1953 book—and a 1967 movie—helped mobilize a campaign to save the remaining Canyon burros.

In the early 1950s, Marguerite Henry, successful author of horse stories like Misty of Chincoteague, stumbled on a 1922 Sunset Magazine article written by Thomas McKee, entitled “Brighty, Free Citizen: How the Sagacious Hermit Donkey of the Grand Canyon Maintained His Liberty for Thirty Years.”

Henry wanted to know more about the scrappy little burro. Traveling from her home in Illinois to the Grand Canyon, she interviewed park rangers and wranglers about Brighty and his kin. She rode a mule down steep canyon trails, and drank from Bright Angel Creek (for which Brighty was named). As she wrote, “I wanted to know just how cold and delicious it was. And I sampled the burro browse [plants that burros graze on] that grew up in sprigs through the rock crevices; I had to know how it would taste. And I hiked part of the way, making believe I was Brighty.”

Her resulting children’s book Brighty of the Grand Canyon won the William Allen White Children’s Book Award, and sold like the hot cakes her four-legged protagonist craved. Readers fell hard for the tough, free-spirited little burro.

But that didn’t improve the fate of the Canyon’s real-life burros. Rangers were still hunting them, even, in the 1960s, hanging out of military helicopters to get a better shot.

Meanwhile, Brighty was morphing from book character to movie star. In the early 1960s, Betty Booth bought a book for her kids, but it was her husband, Steve Booth, a newspaperman and TV producer, who fell hardest for Brighty of the Grand Canyon.

Fighting industry assumptions that Disney had a monopoly on animal stories, Booth raised money to produce the feature independently, hiring the director Norman Foster (of Davy Crockett fame) and casting Joseph Cotten, who appeared in Citizen Kane, as the game warden Jim Owens. Jiggs played Brighty, and there was even a stunt double donkey, unnamed in the credits.

In 1966, Booth had the sculptor Peter Jensen create a life-size, 600-pound statue of Brighty to help promote the movie. In late 1967, Booth gave the statue to the park, braving a snowstorm to make sure Brighty arrived safely at his new home.

The Brighty statue was on display at the South Rim Visitor Center for a decade before controversy compelled park officials to hide it away.

From 1968 to 1977, as rangers continued to shoot burros, the Brighty statue became a visitor favorite. The problem? The statue’s presence at the Visitor Center implied that burros were an integral and beloved part of the Canyon—a blatant contradiction of the park’s beliefs and practices.

People soon sniffed out the inconsistency, both in the Canyon and beyond. Feral equines were raising dust all over the West. The Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act, which Congress passed unanimously in 1971, called the animals “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West,” to be protected from “capture, branding, harassment, or death.” However, the National Park Service’s mandate to protect native ecosystems from invasive species trumped the Act, at least until an outraged public started weighing in.

In 1976, the park service came out with another removal plan, as always favoring elimination over relocation, which would cost over $1,000 per animal. This time, the public pushed back, with town meetings, newspaper editorials, and save-the-burros letter-writing campaigns. The Brighty statue, which had come to represent all imperiled burros, became a flashpoint in the conflict. In April 1978, park officials put Brighty away in storage, hoping the burro hubbub would soon die down.

The plan backfired. Those protesting the park’s burro removal policies now also bemoaned removal of the statue. Their “Bring Brighty Back” campaign got a boost when Marguerite Henry herself began urging her readers to protest both the burro killing and the statue’s disappearance.

Brighty and his brethren had allies far beyond Henry. The Fund for Animals, an animal protection organization formed in 1967, raised $500,000 to helicopter 577 Canyon burros to safety in the early 1980s. They were moved to the FFA’s Texas ranch; many burros were adopted by individual animal lovers.

After the airlift rescue, rangers killed the few remaining burros, and built a fence along the park’s western boundary to keep other burros out. Today, there are few, if any, burros left in the park, though mules—the offspring of a female horse and a male donkey—still reign supreme in the Canyon, not as feral creatures but as beasts of burden.*

Responding to public outcry, park officials brought Brighty out of storage in 1980, this time finding him a home on the North Rim, where he’d spent his summer months. The Grand Canyon Lodge, the statue’s current residence, was built on the site of the original tent cabins that the McKees, Brighty’s adopted family, rented out to early tourists.

“When you first walk into the Lodge, what jumps out are the giant picture windows and the sweeping views of the Canyon,” says Emily Davis, Public Affairs Specialist for the park. “Then you turn around, and there’s Brighty, his nose shiny from the thousands of hands rubbing him over the years. Aside from the view, he’s one of the most photographed things in the Lodge.”

If the statue saga has a happy ending, the real-life demise of Brighty does not. In 1922, Brighty was snowed in with two desperados. Trapped in a cabin for three months, the men survived but Brighty didn’t—one night, he was made into burro steaks. When the meat ran out, the men boiled Brighty’s bones for soup.

Not surprisingly, Henry’s book skirts the truth of Brighty’s last days. Both the book and the movie avoid portraying how the beloved burro died. Instead, Henry emphasizes that Brighty lives on, a shaggy little form still seen on moonlit nights, “the roving spirit of the Grand Canyon—forever wild, forever free.”

*Correction: This article previously stated that mules are the offspring of a female donkey and a male horse. Mules are, in fact, the offspring of a female horse and a male donkey.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook