Decoding the Design of In-Flight Seat Belts

Why we buckle up differently in cars and planes.

The standard economy-class airplane seat has a few hallmarks. The tray table on the back of the seat in front of you, secured by a swiveling plastic pin. The button on the armrest for reclining your seat, which is an extremely rude or totally fine thing to do, depending on your point of view and, perhaps, the duration of the flight. And then there’s the seat belt.

What is the deal with this seat belt? It is not like other seat belts. It is a lap belt only, in two pieces, secured by an industrial-feeling flip-flop buckle that sits directly in the center of the lap. Car seat belts are not like this. Even race car seat belts are not like this. In fact no other modern seat belt is like this. This seemed like a reasonable and even innocuous subject to investigate.

The FAA declined an interview request. AmSafe, probably the biggest manufacturer of aircraft seatbelts, did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Various air travel safety experts either did not respond, stated that they did not know anything about seat belts, or declined to comment. One prominent manufacturer did agree to an interview; two nice engineers answered my questions, and then insisted that I not use their names in any article. Amy Fraher, the author of The Next Crash: How Short-Term Profit Seeking Trumps Airline Safety, actually ended an email with this sentence: “Nobody wants the public to know the truth!”

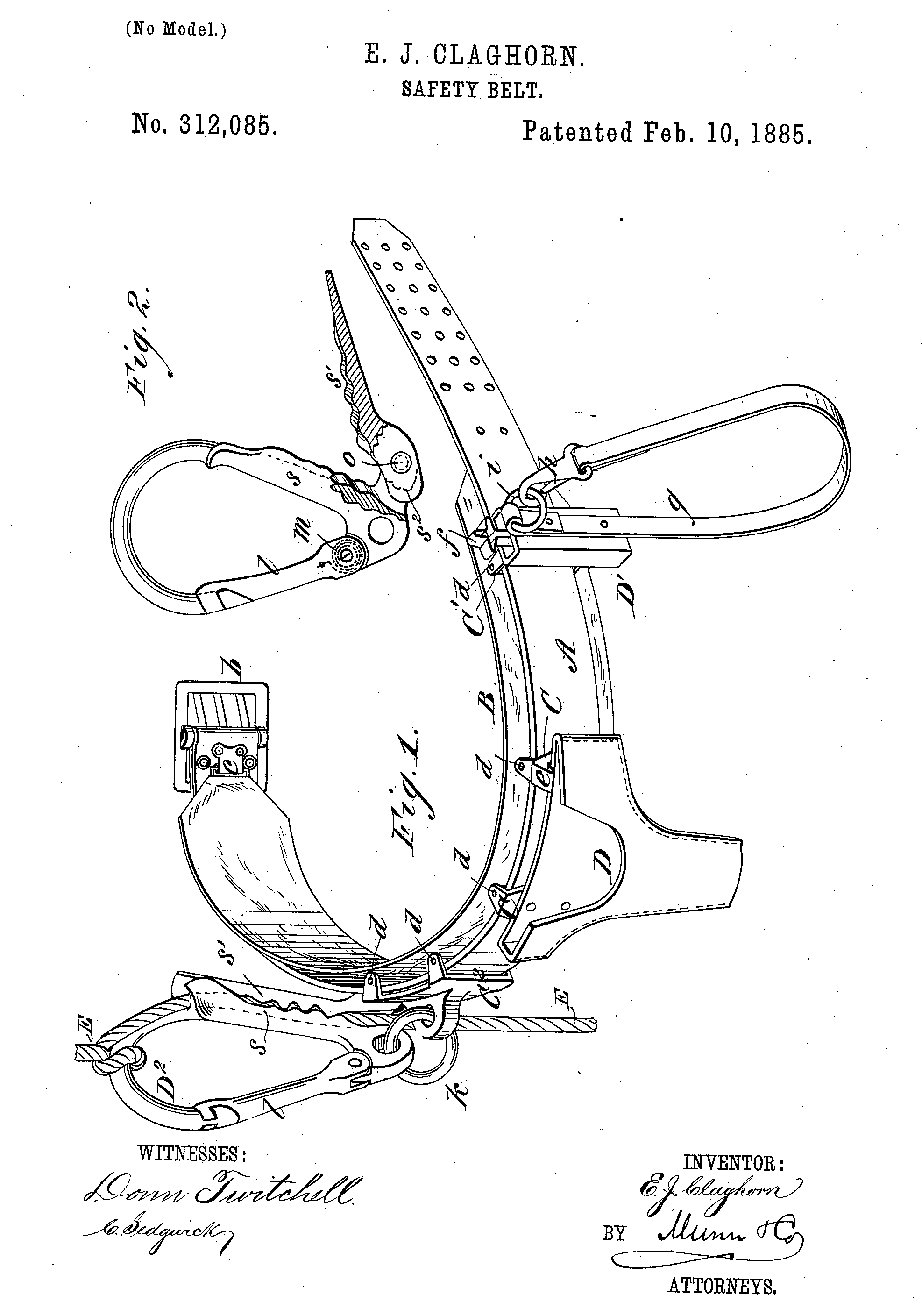

Seat belts, or safety belts, or restraints, have been around since well before airplanes, or even cars, having been patented in the U.S. for the first time in 1885. They were not found in early cars, and remained at best an option in certain forward-thinking automaker lines, most notably Saab, until the late 1950s. In 1966, the publication of Ralph Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed, which attacked the auto industry for refusing to institute basic safety features in its cars, prompted the first American law to require all vehicles (except buses) to provide safety belts.

Seat belts became common in airplanes by the 1930s and 1940s, though even in 1947 there was pushback from the airline industry. (They often insisted that a tight belt could cause internal damage upon a crash. This is very rarely true and also pales in comparison to the number of injuries, internal and external, that are caused when a passenger doesn’t wear a seatbelt.) The Federal Aviation Act of 1958, spurred by several airplane crashes, began the move towards better safety requirements; these were codified in 1972 and have been occasionally updated ever since.

The specific buckle I’m talking about here, which is widely used in economy class, was already old-fashioned by 1972. It’s called a “lift lever buckle” in the industry, and it was common in the first few decades of mass-market cars, but by the early 1970s had widely been replaced with what are called “push-button” buckles, some version of which is likely in your nice modern car right now. Also by this time, some carmakers, especially luxury or more experimental carmakers (read: Swedish carmakers), were playing around with what’s called the three-point harness. That’s the standard seat belt in cars now: it’s a two-part belt that includes a shoulder belt that goes across the chest as well as a lap belt, and which buckles at the hip.

There are a few reasons why the lift-lever lap belt vanished from cars but not from airplanes. For one thing, a shoulder harness in a car is attached to the car’s frame, a very sturdy part of the car. In an airplane, it would have to be attached to the wall (“bulkhead”), which is less sturdy. You could attach it to the seat, but you’d have to reinforce the seat, which increases weight, which we don’t want.

The buckle itself has the benefit of being fairly secure—it’s hard to unlock it accidentally—but fairly easy to unlock in an emergency. A car-style push-button buckle, which is typically mounted at the hip, could open on impact if something bangs against the button. And given the meager room in economy class, nobody wants to be digging around between the seats to find a buckle in a crash situation.

Lift-lever lap belts have remained basically unchanged for decades, aside from a shift in the material of the strap itself to be less stretchy. That makes them deliciously cheap for notoriously budget-conscious airlines. “I suspect that the silly antiquated seat belts we still use as passengers are accepted because they are FAA certified to meet minimum safety requirements in a crash, they are light and cheap,” writes Faher.

But cheapness isn’t the end of the story. Airplane safety is not like automobile safety, because airplanes are not like cars. The primary goal of an aircraft seatbelt is not to save your life if the plane crashes; in that unlikely event, there’s not much in the way of conventional safety gear that would help you. You can survive a car crash in which the car is totaled; your chances of survival in an equivalent plane crash are significantly less rosy. So aircraft safety belts are designed to keep passengers in their seats during minor and more common events, like turbulence or collisions on the runway. In those instances, what you really don’t want is to be unsecured in an outrageously fast-moving vehicle, free to bang your delicate meat body into walls, ceilings, chairs, and other people.

Another primary difference is in the way airplanes move, compared with cars. Car accidents typically involve forward or backward or sideways motion, because cars generally stay on the ground. With that risk, you want a shoulder belt: it’ll stop your entire upper body from bouncing around due to sudden acceleration or deceleration. But in a plane, it’s more likely that you want to protect from up and down movement, as with turbulence. And a shoulder belt doesn’t do you much good for that.

Because the goal of an airplane seat belt is different than that of a car’s seat belt, it’s permitted to be different. The metric you have to know here is called “pitch,” which is the distance between your seat and the seat in front of you (or the wall in front of you, or the wall next to you, or whatever’s around you).

The FAA figures out safety needs by placing a crash test dummy with an accelerometer in its head in a seat and crashing it. The amount of speed the dummy’s head gets up to before smashing into something determines what kind of safety harness you need. The more speed, the more protection you need; more speed is more danger. If this is a confusing idea you can try banging your head slowly into a wall and then very very quickly into a wall. When you’ve regained consciousness, you’ll understand how this all works.

The more pitch between your noggin and the obstacle around you, the more room you have to accelerate, and thus the faster your fragile brain case will smash. The FAA’s regulation thus means that the more room you have, the more serious your restraints need to be. In an economy seat, the only thing you can really hit is a smooth seatback in front of you, and it’s also about nine inches away from your face, which doesn’t give you much room to accelerate and thus decreases your restraint needs. In first class? You have more room, and more danger, and so in the few planes to have instituted three-point harnesses like in cars, they’re in first or business class. (Also, replacing seat belts is expensive.)

For the pilot and crew, the needs are even more intense. A pilot has a lot of room to move around, and also a whole lot of pointy things to smash into in the event of a crash or disturbance. So pilots usually have five-point harnesses, similar to what you’d see in a race car’s cockpit. Same with small planes; shoulder harnesses have been required for all passengers in small planes since 1986, and though pilots sometimes scoff, Flying Magazine notes how important they can be.

That said, a three-point harness is not less safe than a lap belt in economy class; a lap belt is simply sufficient according to current FAA regulations. There is, according to interviews with injury research specialists, very little data on how shoulder harnesses and other restraints in general would affect the safety of airplane passengers. And without data pushing the airlines to invest in different harnesses, they’re perfectly content to follow the letter of the law.

Back in 1993, an advisory circular from the FAA made a strong argument for installing three-point shoulder harnesses, just like in cars. A quote: “Accident experience has provided substantial evidence that use of a shoulder harness in conjunction with a safety belt can reduce serious injuries to the head, neck, and upper torso of aircraft occupants and has the potential to reduce fatalities of occupants involved in an otherwise survivable accident.”

And yet even then, the FAA did not seem to have much confidence in the cooperation of the airlines. Again, from that circular: “It is often heard that a shoulder harness is cumbersome, unwieldy, hot, and uncomfortable to use. Such objections for not installing and using a shoulder harness should be dispelled in view of the benefits gained from a correctly designed, installed, and used shoulder harness-safety belt system.” That circular is just a guide to anyone wanting to install shoulder belts in their airplane; it’s an elaborate consideration of all the best practices for upgrading, not a suggestion that shoulder belts be mandatory. Even so, it makes a pretty decent argument for not retaining the absolute minimum in safety restraints.

The aircraft industry has made some minor steps towards upgrading this system, instituting belts that actually have little airbags right in them. But the venerable lift-lever lap-borne seatbelt costs about $50 each, and passes the FAA’s requirements. So they remain in our seats.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook