Why Is a ‘Pepper’ Different From ‘Pepper’? Blame Christopher Columbus

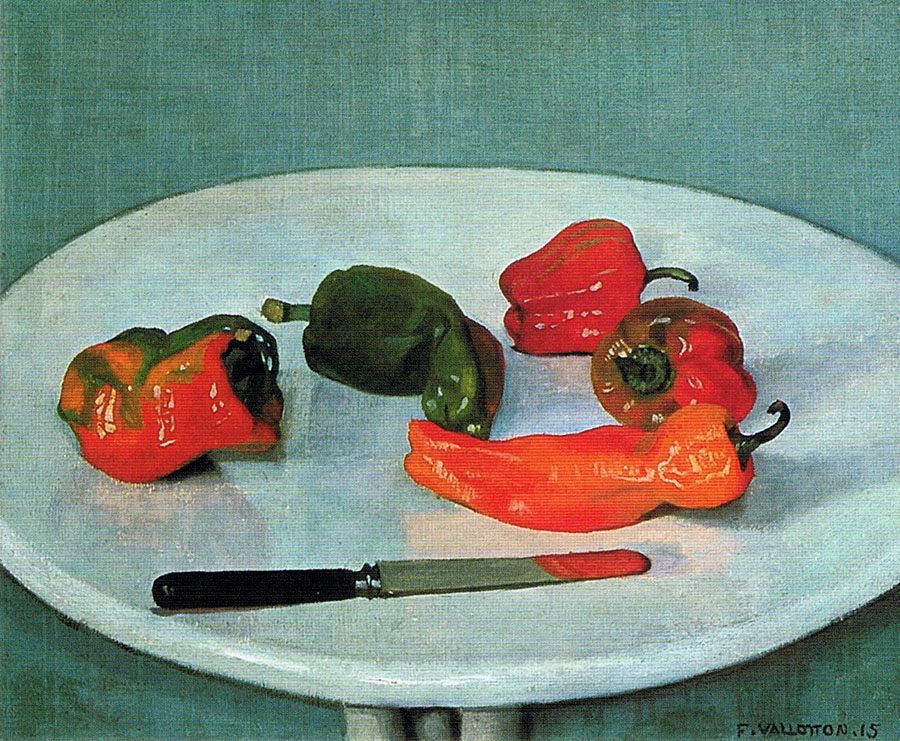

Black pepper and chili peppers have little in common.

Christopher Columbus had a problem.

Less motivated by discovery than by opportunity, he had promised the riches of Asia to his patrons, Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain. Against all odds, he had sailed across the Atlantic and docked in the Caribbean, where the Taíno ate plants and foods Europeans had never seen or tasted. These included members of the capsicum family, which today range from sweet bells, to the ubiquitous jalapeño, to the lethally hot Carolina Reaper. Their heat gave Columbus an idea: He could equate the fleshy fruits with pepper, or pimiento.

This was an inspired decision. “Second only to [gold], Ferdinand and Isabella hoped for black pepper” from Columbus’s expedition, writes Richard Schweid in Hot Peppers: The Story of Cajuns and Capsicum. Instead, Columbus came across what the Taíno called axí, or the unrelated capsicums. They ate the spicy berries abundantly, Columbus wrote in 1493. Already, he began to build their profile. The peppers, he wrote, were “more valuable than the common sort”: that is, more valuable than black pepper. Not only that, but they could be attained much more easily than the fabulously expensive black pepper. “Fifty caravels might be loaded every year of this commodity at Española,” he wrote. His mercantile-mindedness made sense. One of the reasons the Spanish monarchs wanted pepper so badly was that the rise of the Ottoman Empire cut off the traditional pepper routes from Asia.

Black pepper (Piper nigrum) had been a culinary mainstay of fine cuisine since the Roman Empire, beating out prior spicy compounds such as horseradish, mustard, and the arguably better long pepper. It was a valued addition to both food and medicine, yet getting it from Asia was expensive and difficult. Columbus was so eager to find pepper that he carried peppercorns with him. When he landed, he showed them to locals. They were similar enough to the allspice berries growing wild in Jamaica that Columbus also likened them to pepper: pimienta de Jamaica. Marjorie Shaffer writes in Pepper: A History of the World’s Most Influential Spice that Columbus was likely smart enough to know what he had wasn’t pepper, but that he probably didn’t care. Allspice and hot peppers headed for Europe.

Yet dishes such as the Spanish pimientos de Padrón and Italian ‘nduja were still a ways off. For a few years, hot peppers were grown ornamentally, but within decades they were ubiquitous in Europe. Before long, the seafaring Portuguese took them to Asia. Since hot peppers grew easily in temperate weather—unlike black pepper—they were gradually and happily adopted by chefs looking for some heat.

But some people weren’t happy. Dutch traders, writes Roger Owen in The Oxford Companion to Food, “feared that this cheap new spice would outsell their expensive one,” especially because of its association with exquisite black pepper. The Dutch, who would dominate the world’s spice trade, never managed to commercialize hot peppers as they did cinnamon and nutmeg. But they did try and enforce a different name for the spice: the Nahuatl, or Mexican term chilli. So whenever you need to struggle to specify between black pepper and chili peppers, feel free to blame Columbus.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook