Why Doctors Once Treated Fevers and Hysteria With Mashed-Up Bedbugs

From Ancient Greece through the 18th century, bedbugs were used as medicine.

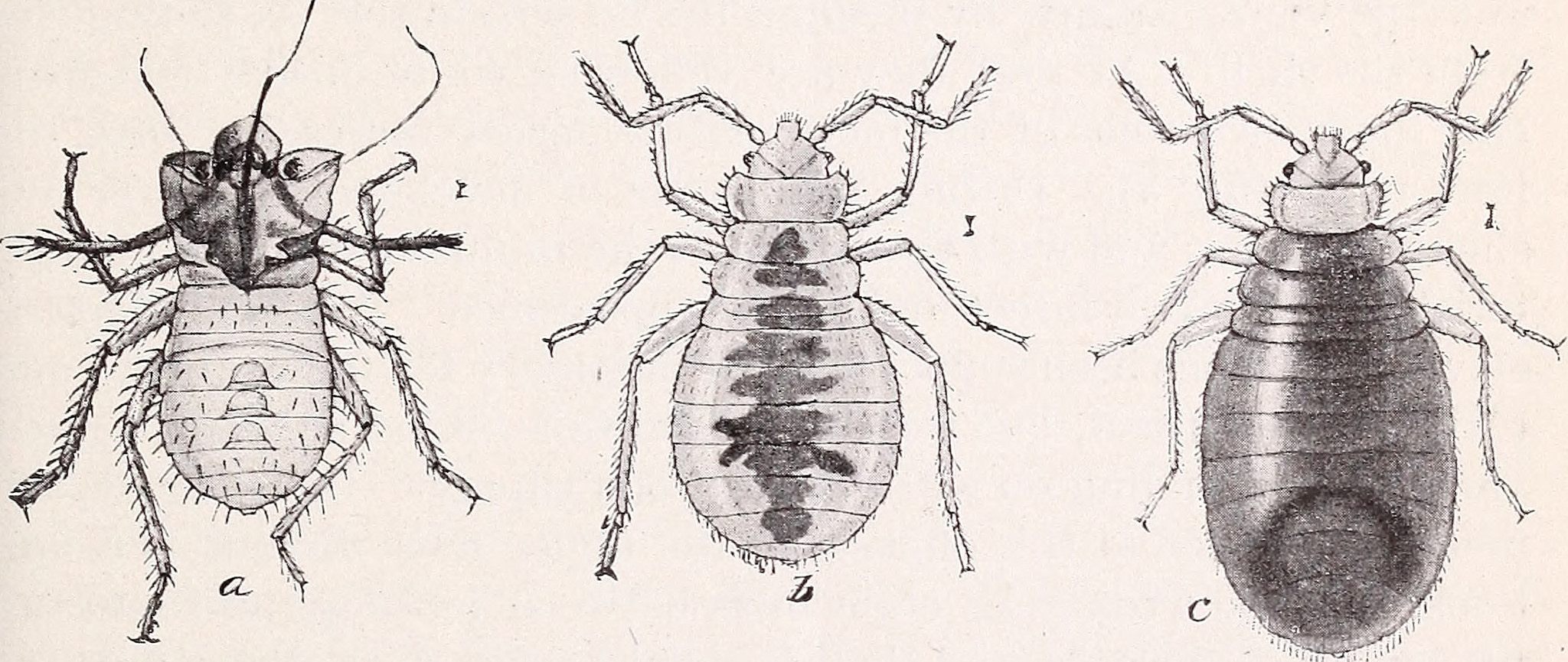

A bed bug at different stages, as depicted in the 1902 book The Bedbug. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Getting sick in the first century was only tolerable if you were not a picky eater. The cure for the flu or any bad fever was simple, according to physicians of the time: mix exactly seven bedbugs with stew, and swallow. Four, if you were a child.

Instructions for preparing “cimices of ye bed”—as bedbugs were known— saw them being “put in meat with beanes, and swalloewed downe before the fitt” as a remedy for sweating sickness,” says a translation of De Materia Medica, a pharmacopoeia written by the Roman army medic Dioscorides of Anazarba.

If you suffered from “scabs of the privities,” bedbugs were equally effective. For eye infections, though, first pound the parasites “in salt and women’s milk,” then apply.

For at least 3,500 years, humans have wanted to be rid of bedbugs. Finding their round, flat bodies at home today causes panic, paranoia, and expensive extermination treatments; many move away from their homes or discard infested objects they once held dear. But from ancient history onward, some physicians used the parasites, in earnest, for medical cures and recipes. The creatures were a medical cure-all beginning in the waning years of the last century B.C.

A digitally colored scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a bed bug. (Photo: CDC/Public Domain)

The 2nd century Roman physician Quintus Serenus Sammonicus even wrote a medical advice poem touting bedbug, or “wall lice” recipes:

Shame not to drink three Wall-lice mixt with wine,

And Garlick bruised together at noon-day.

Moreover a bruis’d Wall-louse with an Egge, repine

Not for to take, ‘this loathsome, yet full good I say.

As the centuries progressed and medicine mostly did not, bedbug-based cures for jaundice, vomiting, lethargy, ear infections, and snake bites snuck into later medical texts. Instead of causing hysteria, bed bugs were actually thought to cure it, specifically the false medical condition of “female hysteria,” which went forward from Ancient Greek thought into western culture, bringing with it the bedbug remedy claimed as its cure.

“In earlier times, having these creatures was sometimes a sign a dirtiness, but was sometimes a sign of holiness—the mortification of the flesh, like an imitation of Christ, was something people in the Middle Ages thought was a good thing,” says Lisa Sarasohn, an Oregon State University historian who is writing a book about the social history of vermin.

A photo from the early 1900s showing a couple looking for bed bugs. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-58969)

While it may seem strange to use creatures that parasitize us as medicine, vermin “had a whole lot of meaning for people in the past,” says Sarasohn, as bugs that shared our most intimate human spaces. Also, bedbugs and other vermin mentioned in cures were plentiful, easy to find, and free.

The preparation of medicinal bedbugs varied depending on the sicknesses they were meant to treat, according to both Pliny the Elder, a devout advocate of bedbug medicine, and De Materia Medica. Swallowing them without beans can help those who were “bitten by an Aspick,” but drinking them with wine or vinegar will expel horse leeches. If “put into the Urinary Fistula”, pulped bedbugs would “cure the Dysuria,” or difficult or painful urination.

De Materia Medica became the precursor to western pharmacology and influenced medicine for the next 1,500 years, with some of its bedbug cures surviving in Europe for centuries. The 16th century medical book Treasury of Health by Humphrey Lwyd, for example, was a translation of an older Greek medical book with commentary added in. For malaria, then called “melancholy putrified,” Llwyd recommends stuffing a bean with bedbugs, to “take awai the fever.”

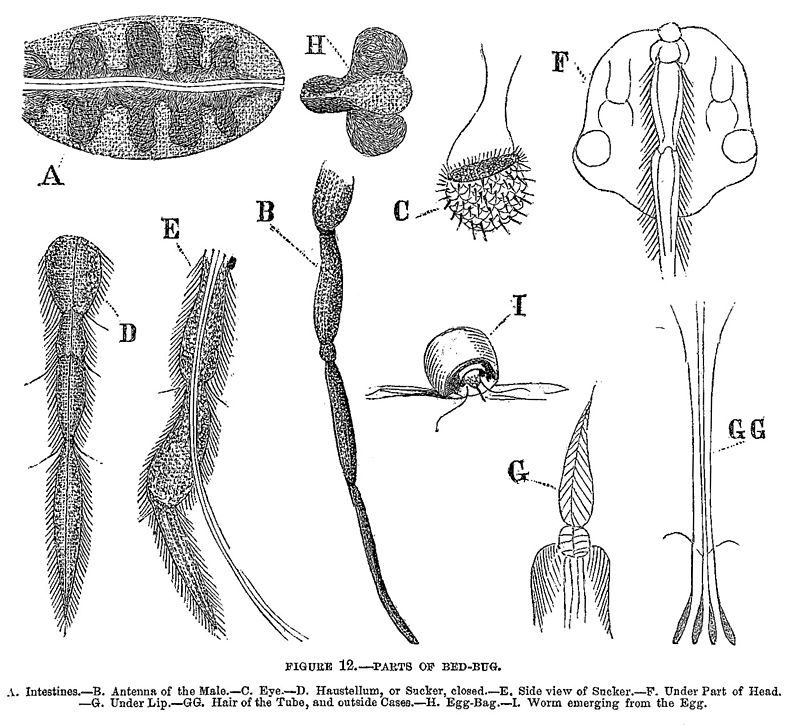

An engraving from 1860 showing different parts of a bed bug. (Photo: Public Domain)

These were far from fringe medical practices at the time; in fact using bedbugs are a cure was fully in line with the tenets of homeopathy devised in the 1700s. “If something looks like or is the same color as the disease you can cure the disease” was the line of thinking, Sarasohn says. At the time many medical experts believed in another ancient Greek medical theory called the four humours, which sought to fix a perceived imbalance of blood, phlegm, yellow bile or black bile.

The smell of bedbugs was especially key to their supposed medicinal qualities. Just sniffing any kind of lice could cure a nosebleed, and the scent of mashed bedbugs could reverse cataracts, lethargy, earaches, and even kidney stones. “They thought that bedbugs smelled a lot —apparently they do smell a little bit like coriander, and that was considered a terrible odor in the 18th century,” says Sarasohn. “When anybody is writing about bed bugs, they’re writing about how nauseating they smell.”

This smell supposedly treated hysteria, a now-disproven condition that Plato (and many doctors into the 1800s) believed plagued women with a “wandering womb,” meaning their uteruses detached and floated around the body, causing libidinous behavior and anxiety. In some cases, a strong smell was said to lure the wiley organ back into place: The 18th century French naturalist Jean-Étienne Guettard, “recommends Bugs to be taken internally for hysteria; and a Dr. James says “the smell of them relieves under hysterical suffocations,” notes Frank Cowan in Curious Facts in the History of Insects.

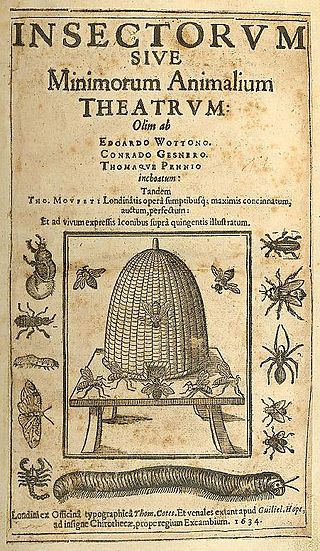

The title page of Thomas Muffet’s The Theatre of Insects, from 1658. (Photo: Public Domain)

Thomas Muffet, a 16th century medical enthusiast and writer who may have inspired the “Little Miss Muffet” nursery rhyme, thought bedbug-derived cures were genius, and tells readers all about them in his 1658 volume The Theater of Insects (published posthumously). One favored remedy included mixing bedbugs with tortoise blood to cure snakebites. Another saw the creatures mixed with wine, admittedly “a remedy to be despised.” Other vermin proved effective as well: “Many English men have learned by experience,” Muffet adds, “that one dram and a half of Sheeps Lice given in drink will soon and certainly cure the Jaundies.”

The scientific method seems to have been applied to bedbug cures with some rigor as well: Muffet cites how Conrad Gesner, a 16th century physician, tested bedbug-based medicines “amongst the common and meaner fort of people in the Countrey” with success. Not only could bedbugs cure bites and stings, but will “provoke urine” as a diuretic and “stop children’s water that goes from them against their wills”—a cure for bedwetting.

Bedbugs, however useful, were not wanted in the bedroom in the 17th century, and even more so in the 18th, when common attitudes toward the parasites began to change. “As Europeans come into contact with other people around the world, they really start to not want to be around parasites, and really start using them to characterize anyone they didn’t like,” Sarasohn says. “The English, for example, thought the Scots were teeming with lice, and called Scotland lice-land.” By then, people were examining their world with microscopes, and the upper classes began to use cleanliness to distance themselves from the lower classes.

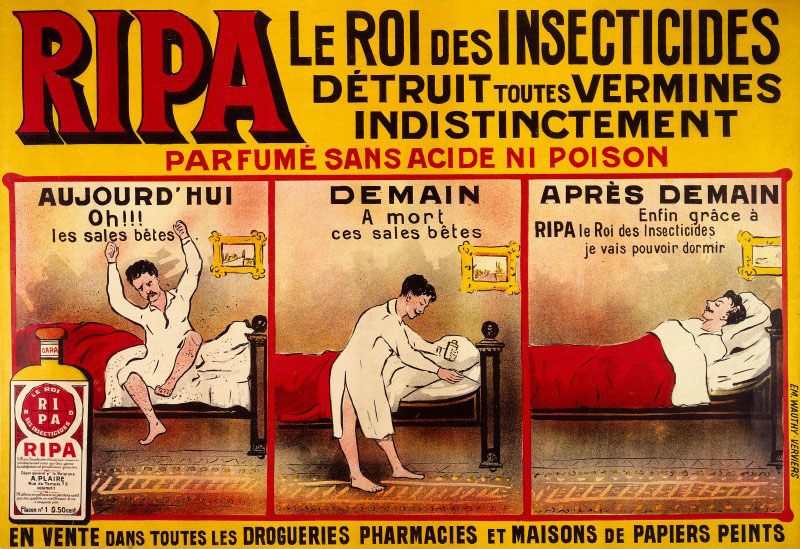

An advertisement from 1900 for a bed bug killer. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/ CC BY 4.0)

“The first exterminators who advertise they can rid you of bed bugs arrive in the 18th century,” Sarasohn adds. Bug killers from that period are sometimes even more elaborate than bug-filled cures. One bedbug-killing recipe calls for “Smoke of cow dung and rotting cucumber and ox scale combined with vinegar,” another asks for “Droppings from a roasted cat with egg yolks and oil to form an ointment which could then be rubbed onto infested furniture.”

Popularity of bed bug cures declined. While bed bugs and lice were still home-made cures for tumors and goiters in the late 19th century, Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal writers criticized old-school remedies, saying they “can see nothing very extra ordinary in such demonstrations consequent on swallowing a bed bug.”

The idea that parasites had the ability to heal didn’t disappear completely, though. In 2002, the authors of the pest management guide Ask the Bugman found an unexpected repository of Ancient Greek medical knowledge in the Midwest. “In some parts of Ohio, eating seven bedbugs mixed with beans is considered a cure for chills and fever,” they wrote. It was exactly the same number of bugs recommended in De Materia Medica.

While some of these cures seem strange, in many ways human terror of bedbugs was exactly what drove people to turn to them for relief—they wanted to find some way in which the creatures’ torments made sense. As Muffet once said, “by the conduct of nature hath produced nothing that in some part is not good for man, and therefore that which the Comedian God thought hurtfull, mans posterity hath found beneficiall.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook