Why Europe’s First Celebrity Chef Named His Dishes After the Rich and Famous

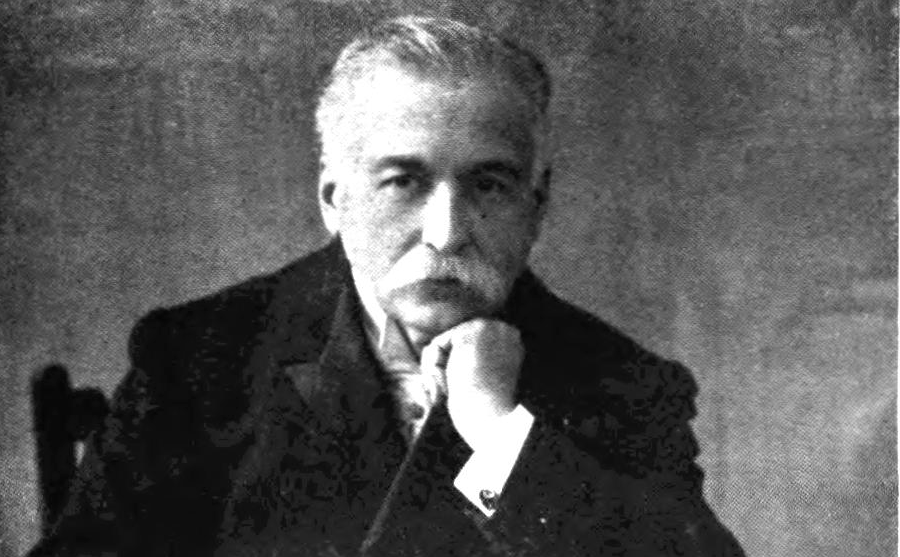

Auguste Escoffier was the all-star genius behind Melba toast.

Without Georges-Auguste Escoffier, there could be no Gordon Ramsay. No Nigella Lawson, no Alain Ducasse, not even—perish the thought—Guy Fieri. Escoffier has some claim to being not just the first celebrity chef, but the first person even to invent the concept, through a unique career that spanned decades, countries, and seven cookbooks. In the late 19th century, Escoffier set a precedent in which the chef came out of the kitchen and into first the dining room, and then the limelight. The hundreds of dishes he named after the Belle Epoque’s superstars were just one small part of how this culinary luminary helped transform modern cheffery.

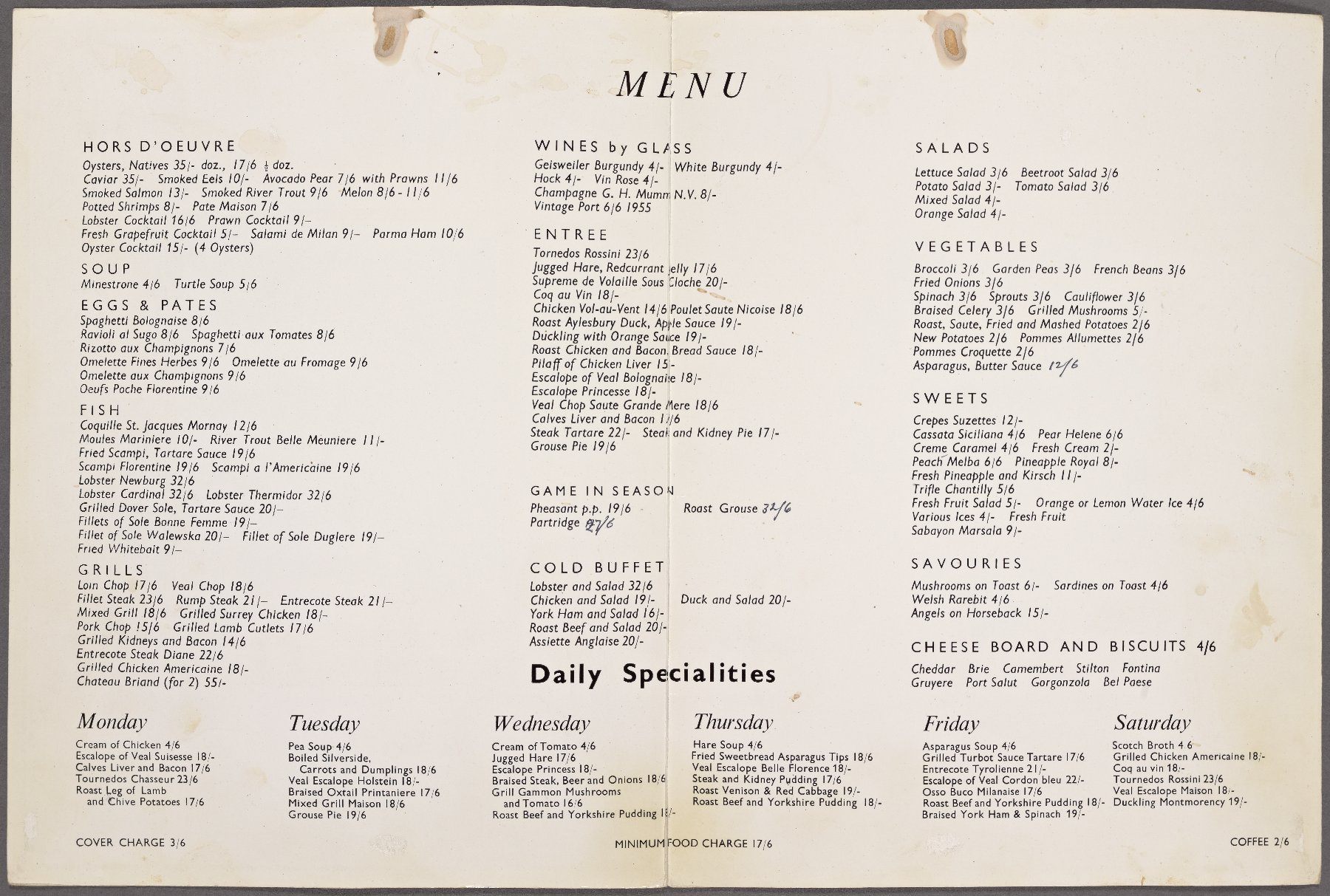

Escoffier came up with thousands of new recipes, many of which he served at London’s Savoy Hotel and the Paris Ritz. Some were genuine leaps of ingenuity, others a twist on a classic French dish. Many carry someone else’s name. In early dishes, these are often historical greats: Oeufs Rossini, for the composer; Consommé Zola, for the writer; Omelette Agnès Sorel, for the mistress of Charles VII. Later on, however, Escoffier made a habit of giving dishes the handles of people who, in their day, were virtual household names: An entire choir of opera singers’ names are to be found in Escoffier’s cookery books. The most famous examples are likely Melba toast and Peach Melba, for the Australian opera singer Nellie Melba, though there are hundreds of others. But why did he do it?

Before Escoffier, being a chef to even the most glittering names of the Western world was dirty, low-status work, says Luke Barr, author of the forthcoming biography Ritz and Escoffier: The Hotelier, The Chef, and the Rise of the Leisure Class. “Chefs were working-class guys,” he says. They’d start working in the kitchen as teenagers and spend years in hot, grimy conditions behind the scenes, usually well-lubricated by furtive swigs of something strong. But Escoffier had another vision for his kitchen, of which cleanliness, serenity, and sobriety were all key. The kitchen was to be a spotless oasis of calm, and Escoffier its wholly presentable figurehead, clad in dazzling whites. For the first time in the history of Western dining, the chef would go out and greet guests, Barr says. This was previously unheard of. “They were servants. They were not someone whose name you knew, or someone you talked to—until this period, when that started to happen.”

Escoffier wasn’t just a culinary genius, however—he was a tremendous charmer whose guests quickly warmed to him. Nathaniel Newnham-Davis’s 1914 Gourmet’s Guide to London dedicates some paragraphs to describing his “commanding personality”—how this smallish man, mustachioed like a walrus, had “the face of an artist, or a statesman.” (“Had [he] been a man of the pen and not a man of the spoon,” he wrote, “[he] would have been a poet.”) Even his slight quietness, Newnham-Davis wrote, belied the Maître-Chef’s knowledge, authority, and “capacity for command.” And he was as flirtatious as he was charismatic, says Barr. “He loved to talk to women, especially.”

Just a few decades earlier, neither chefs nor female guests would have been in the high-end dining rooms of Europe’s capitals. Restaurants had previously been the domain only of the men who could afford to eat there. Chefs and other staff were swept out of sight, and women safely ensconced in the home. At a push, men might meet their mistresses or high-end sex workers in private rooms, but by and large most high-end restaurants were virtual boys’ clubs. All that changed in the late 19th century, as women began to have more and more independence and, in turn, to venture into restaurants. A third social change was also taking place: the professionalization of acting and opera. This transformed female actors and singers from “fallen women” into stars, worthy of respect—and of places in Europe’s most salubrious dining establishments.

Many of the female celebrities who inspired Escoffier’s dishes, therefore, were pioneers in their own right. They came to restaurants in the grandest hotels of London, Paris and the French Riviera both for recreation and to be seen by others in their wider social circle. There, decked out in the latest fashions, guests would peer past one another, surreptitiously taking note of which notable figures were to be found under the gilded ceilings. At his hotels in Paris and London, the Swiss hotelier César Ritz, Barr says, made a point of choosing lighting that would illuminate diners as flatteringly as any portrait in a gallery. “And they were celebrities, they were opera stars, they were courtesans, whatever,” says Barr. “More and more, Escoffier would name his dishes for these women.”

The reasons for this are many and various, and unpicking them requires a little background knowledge on how Escoffier ran his restaurants. As in many high-end hotels today, Escoffier kept complex dossiers of notes on his customers. He would meet with diners, chat to them about their likes and dislikes, and plan menus accordingly to prevent repeats. “And that eventually led to the mythology of Escoffier: That he would give you the perfect dinner, exactly what you wanted,” says Barr. “A perfectly balanced menu. And one of the reasons he was able to do that was because he was keeping close records of what people did and didn’t like.” A dish specially designed according to someone’s tastes, therefore, might well end up bearing their name.

There was a certain amount of self-fashioning to this, too. “It was a symbiosis between the fame of the clientele and the growing fame of the chef,” says Barr. A little-remembered dessert, Poires Mary Garden, combines syruped pears with softened cherries, raspberry sauce, and whipped cream. Today, Mary Garden has faded from public memory, but at the time, she was one of the best-known opera singers in the world. Having her name on his menu spelled out the ilk of Escoffier’s clientele and, in a way, allowed him to attach himself to these leading lights. “He stole a little bit of the cachet and the glamor of his celebrity guests by naming a dish after them,” Barr says.

For the French opera singer Emma Calvé, it was a dessert of vanilla ice-cream and cherries stewed in Kirsch. For Italo-French Adelina Patti, a stuffed chicken dish with artichokes and rice. French singer Jeanne Granier is memorialized in an egg concoction involving asparagus and truffles, and the actress Sarah Bernhardt in a strawberry dessert, a chocolate-gilded macaroon, and a veal broth. Having a dish named after you by a chef as great as Escoffier was an honor, and guests were usually quite flattered. Nellie Melba, in her likely ghost-written memoirs, makes the distinction between this and between the irritating vogue of celebrity names being exploited to sell bootlaces and cigarettes. He had come up with the dish especially for her, and asked if he might name it accordingly. “I said that he might with the greatest pleasure, and thought no more of it.”

In her autobiography, Melba dates the dish around 1904, and claims to have eaten it at the Savoy. As Escoffier was dismissed from the Savoy in 1898, it is likely she misremembered some of the details. Either way, by the time the decade was out, the dish was everywhere: from Rules, in London, to New York’s Ansonia hotel, one of the grandest in Manhattan. If you didn’t like that version, Hotel Knickerbocker, down the road, had their own, as did the St. Regis Hotel. It appeared in Chicago and Washington D.C., and on the menu of Belfast’s Ulster Club. It was everywhere. Many chefs palmed it off as their own creation, Melba wrote, describing irascible fights between herself and upstart pretenders: “I think we should give credit where credit is due. And it certainly is due to Escoffier.” Neither Melba nor Escoffier saw a cent from these imitations, though the dish’s runaway success can hardly have knocked back either of their rising stars. In fact, Newnham-Davis described how the invention of Peach Melba “added a new glory to a great singer.”

A dish honoring a celebrity guest didn’t just benefit the chef or his muse, however. Ordinary members of the public extracted a certain joy from eating like the glitterati. Like anyone who has ordered a martini and fancied themselves James Bond, so diners at the Savoy or the Ritz might have ordered Edward VII Lamb Chops and tasted a few mouthfuls of royal treatment. “You’re participating in the glamor at one step removed,” says Barr, “but you can still enjoy it.” Today, many of these recipes are forgotten, but each retains a little stardust—a written record of a time when the world’s most famous chef was naming dishes for the world’s most famous people.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook