Why There’s No ‘Right’ Way To Speak English

The English language is the ultimate code-switcher, gaining multiple personalities when it travels.

A sign in Singapore with the four official languages: English, Mandarin, Tamil and Malay. (Photo: Public Domain)

Jenny Suomela grew up in Sweden, but began learning English in school as a young child. She currently lives in the United States, and is married to a man whose only language is English. If she’s speaking with Swedish friends, however, you might hear more than a few English words and phrases thrown in: “det är awesome”, for example, means “it is awesome.” Popularly called Swenglish, this use of English in Sweden is a mix of the two languages; a practice common throughout the world.

This melding of English with other tongues has become increasingly pervasive, used in schools, business meetings, online forums, and everywhere in between. There are estimated to be two billion people speaking dozens of varieties of English in the world, a number far beyond the estimated 340 million native English speakers. “I think there is international awareness of the global role of English, mainly because it is so ubiquitous, and inescapable,” says Robert McCrum, author of the book Globish and co-writer of the BBC series and book, The Story of English.

But English isn’t just influential in the world; it’s completely influenced by every place it goes and changed by the people who use it, sometimes immutably. Both locally inflected new words and lingual blends that may be unintelligible to people who only speak Britain’s Standard English have been added to the versions of English taught in global schools. These versions are then used by vast numbers of non-native speakers separated by thousands of miles. Not only are all the versions part of the same mother tongue, but they developed at very different times; some over hundreds of years, others in response to more recent exposure to pop culture.

Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament, London. (Photo: Hernán Piñera/CC BY-SA 2.0)

So what goes on when people from other language backgrounds begin adapting English to their own needs? “You’re touching on a very broad subject,” laughs Gregory Guy, a Professor of Linguistics at NYU who specializes in sociolinguistics. “There are a lot of different kinds of things that are involved.”

For one, he says, English is tied to hundreds of cultures from today and the past, in both temporary and enduring ways. As Britain invaded and colonized substantial swathes of the world, a slew of cultures were obliged to add English to their lexicon, with even more words and phrases added once the U.S. became influential in trade and business. For non-native English speaking countries aiming to communicate on a more global scale, or countries that house multiple major languages, English is sometimes used as a middleman; but it also grows into a widespread staple, changing with the cultures of those who use it.

The differences between Standard English and other types of English are described as categories: pidgins, creoles, or dialects, often called varieties. While a variety is usually similar to the standard version of a language, a pidgin is a rough mix of lingual influences, used by people of different native tongues who need a common language to communicate. A creole is a more complex mixture, often spoken and developed over generations.

While word choice can differentiate one variety from another (speakers of Australian English call for a “caretaker” to clean a spill, while an American would call for a “janitor”), spotting the difference between creoles and varieties can be tricky, and linguists themselves don’t always agree.

Malaysian English, the standard version taught in Malaysian schools, includes unique uses of English words; one might ask “why you so blur” if someone is acting a little spacey. But Manglish, the local Malaysian creole, goes a few steps further: speakers may add “lah” or “mar” to the end of some sentences, suddenly showing complex emotional intent that is absolutely necessary if you need to soften the blow of a demand, or apologize. Saying “stop that lah” is a more approachable way to give a command.

In India, according to The World Policy Institute, over “1.2 billion people speak 15 official languages”, with hundreds of others used around the country. The Indian government adopted a policy that teaches Indian English alongside Hindi and local languages in schools (private English-medium school are increasingly popular, too). When English and Hindi mix locally to form the creole Hinglish, however, English grammar works in tandem with Hindi words and phrases. “Mujhe nah lag I will come tomorrow” in Hinglish means “I don’t think I will come tomorrow.”

India and Malaysia were both British colonies and developed their own brand of local English over centuries. Hinglish and Manglish are different enough that speakers of one creole can’t always understand the other, though Standard English is understood by both. But native English speakers have the same problem with other native English speakers. Americans, for example, may struggle when confronted by certain accents and phrases used in parts of England, or even in dialect groups of their home country. So where is the line drawn between a creole and a variety?

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia’s capital. (Photo: Andrea Schaffer/CC BY 2.0)

“It’s difficult to give a hard and fast answer to that,” says Guy, though some linguists use grammar and syntax to distinguish the two. “[Creoles] typically have verbal systems that mark [situational] aspects, like if an action is completed or is ongoing…that standard English does not have.” Another criteria that many linguists use to distinguish creole from variety includes the ability for a non-native speaker to understand it over time: if after a few weeks you begin to understand the language around you readily, it’s probably a variety rather than a creole.

Language modifications can happen relatively quickly. The 1982 BBC series The Story of English filmed girls in the San Fernando Valley of California as exemplars of an odd American dialect. What was so odd in 1982? It was the novel way the girls sprinkled the words “like” and “totally” into their otherwise grammatically correct sentences. Of course, both words are common fillers, or crutch words, in speech modes far beyond that region today. The Valley girls grew up, their dialect use spread, and that influence carried through to the next group of kids.

When adults from varied lingual backgrounds need to learn a second language in order to communicate with one another, a lingual trend similar to the spread of Valley Girl speech begins. New language speakers take influence from their native tongues when forming sentences in the new language; if this need continues, the mix might evolve further. Singaporean English is similar to British English, but the creole Singlish draws heavily from the sentence structure and sounds of Malay and Mandarin, which are more common first languages in Singapore; “I don’t want it” becomes “dowan”; ”what is the time right now?” becomes “now what time?”

A street in Singapore. (Photo: Aleksandr Zykov/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The United States, itself a former British colony, rapidly developed its own American English, influenced by the many Native American, African and European languages over time; Native American words survive, including canoe and raccoon. Americans diverged from British speech, using “will” instead of “shall”, calling time off from work “vacations” instead of “holidays.” In the United States and the Caribbean, these changes sometimes began with the many languages spoken by people who were enslaved. The Gullah people of the coastal stretch from the Carolinas to Florida speak an English creole that comes from such a mix, and went on to give American culture gumbo, chocolate covered peanuts, and the Tortoise and the Hare.

“Slavery is a typical condition for pidgins and creoles to emerge, because you have people who are forcibly obligated to communicate in a new language as adults, but they’re not given a whole lot of access to [study] it,” says Guy. The Jamaican Patois is a creole, rich with its own grammatical structure that came out of this necessity, and exists alongside the more British-sounding Jamaican English. “You get this intermediate variety that emerges that isn’t the native language, nor is it the standard,” says Guy.

While that initial variety is a pidgin, if children grow up speaking this pidgin as their main form of communication, it develops more nuanced cultural influences and syntax, and becomes a creole. Without the original multi-lingual element, however, speakers don’t normally need to form a new language. For example, when Nigerians who spoke the same language were brought to Brazil as slaves, they became bilingual instead of developing a pidgin. “They could speak their language among themselves and then speak Portuguese to the slave masters,” says Guy. “Under those circumstances it’s not often that you get a pidgin or a creole emerging.”

The Sydney Opera House. (Photo: Nicki Mannix/C BY 2.0)

Today, English has become the dominant language of global business, despite the inconvenient fact that English is not the easiest language to learn. “In terms of how readily learnable English is, it’s not that good a choice,” says Guy. “For one, English has a terrible spelling system.” While English vowels are represented by only six letters, A E I O U and occasionally Y, they represent a hard-to-master vowel system, containing 13 to 20 different sounds, depending on dialect. On the other hand, Guy notes that while some languages use multiple genders, tenses, or pluralities, in English phrasings tend to be more open to interpretation; in that sense there’s less to memorize.

Despite this, could the widespread use of English actually morph into a Tolkien-style common tongue? “Whether ‘Global English’ would attain any currency in the future would probably depend on whether there’s a viable competitor in the horizon,” says Alan Yu, a linguistics professor at the University of Chicago. “Perhaps several common languages would pop up around the world.” Yu speculates that maybe a “Global Chinese” and “Global Arabic” could grow alongside other global varieties.

However, translation technology could also challenge English as a global phenomenon in the future, Globish author Robert McCrum points out. “That’s to say, when a Finn or a Malay can write/speak in his/her native tongue and be instantly translated into Spanish, French or Russian or Mandarin Chinese, then there will be less of a need for a global tongue.”

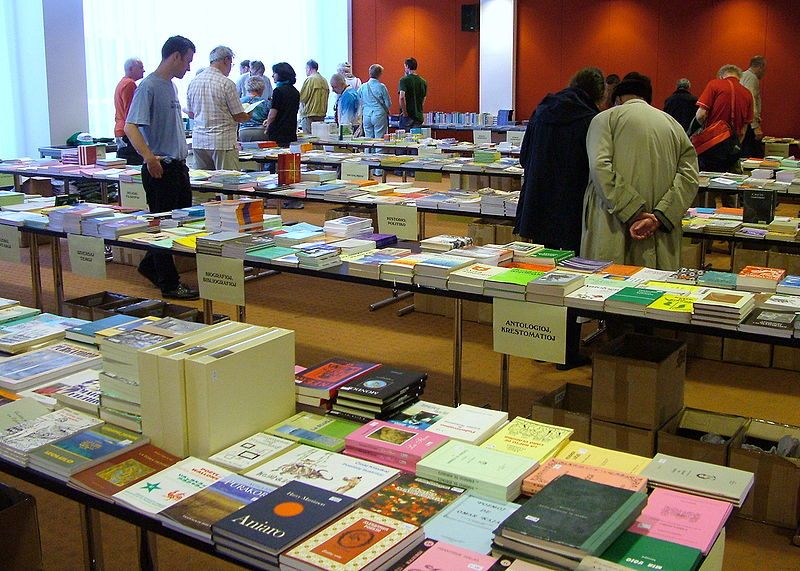

Esperanto books at the World Esperanto Congress. (Photo: Ziko/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Some have tried to make global language a reality, but without much success. “Globish” is now a trademarked term, with proponents advocating a ‘simple English’ with limited vocabulary for business and world communication. Esperanto, invented in the 1800s, is one of the more famous attempts at creating an easy-to-learn world language. Even when accounting for the bias of what makes a language easy versus difficult, though, any attempt at a world tongue has an even larger hurdle to jump: culture.

“If you invent a language, it’s going to take a long time for it to be spoken by a lot of people before it has a whole cultural matrix: the literature…humor, sarcasm, emphasis, questions, anger, happiness..an invented language is going to have quite a job to invent all of those kinds of things,” says Guy. “And who knows whether people would pick it up?”

Without shared culture, a language becomes so obtuse that no one cares to speak it. As the internet and popular media spread accents and phrases, more words can transfer between native and non-native English speakers than ever before: young Serbians speak Serblish on online video games, and one can easily look up and begin using Indian English terms that have made it into the Oxford English Dictionary, like “kitty party”, a social lunch with a lottery, which the winner uses to buy the next group lunch.

Indeed, these changes in words and sounds has always been part of English: after all, Old English is completely unintelligible to speakers of the language today. “We say ‘YOLO,’ we say ‘fuck my life’ a lot,” says Suomela, whose Swenglish-speaking days in Sweden sound pretty similar to those of English-speakers in the United States. As English moves around the world in new ways, the cultural artifacts its speakers bring with them proliferate and evolve; it’s only a matter of time before these changes make English sound like a different language altogether.

Update, 4/5/2016: An earlier version of this story misidentified Alan Yu’s workplace. It is the University of Chicago. We also mixed up “Hindi” and “Hindu” in one section. We regret the errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook