The Zen Beekeeper Returning Hives to the Wild

By handling bees with his bare hands, Michael Joshin Thiele seeks to better understand them.

In recent years, the mysterious disappearance of bees has puzzled experts from across the world. In the United States alone, the honeybee population has dropped by 50 percent from midcentury levels, and 700 species of bees are now at risk of extinction. Scientists can’t really pin down the cause of the “bee apocalypse,” but point to the interplay of toxic pesticides, biodiversity loss, and climate change.

Michael Joshin Thiele, a German apiculturist based in California, thinks a solution may lie in returning bees to the wild. Since their appearance on our planet more than 100 million years ago, bees have been a keystone species for forest environments, where 90 percent of plant life depends on pollination. But with the onset of commercial beekeeping, bees have increasingly lived in settings that are not in line with their natural habitats.

Since 2006, Thiele has worked with a team of biologists, apiculturists, and botanists to run bee rewilding projects, from workshops on how to install log hives in backyards to courses on building bee sanctuaries inside organic farms. In 2017, he founded Apis Arborea, a platform to share apiculture knowledge and information about the essential role of bees. The project’s name encapsulates his philosophy. Apis Arborea means “bee of the tree” in Latin, a twist on the scientific name of honeybees, Apis mellifera, literally the “bee that carries honey.” “We always only looked at bees for what they do for humans,” Thiele says. “It’s time to see them for what they do for our wider ecosystem.”

For Thiele, it all started with a dream. “In February of 2002, I had this incredibly vivid dream about bees,” Thiele says. “I saw a swarm appear suddenly in the wild.” Far from generating fear or dread, this vision left him with a sense of awe for apian life. Other vivid bee dreams followed throughout winter. By springtime, Thiele, who was studying to become a lay-ordained monk at the San Francisco Zen Center, asked a local beekeeper if he could borrow some equipment. The next day, a swarm of bees appeared right outside his home inside Green Gulch, an organic farm run by the San Francisco Zen Center. “I was doing some work in the garden,” he says, “when suddenly my wife calls me and I see a swarm of bees covering my gear.”

Since then, Thiele, a 54-year-old man with a broad smile and intense blue eyes, has dedicated his professional life to bees. After a self-directed training through books and chats with local experts, he served as the official beekeeper of San Francisco Zen Center from 2002 to 2005.

But a few months in, something about conventional beekeeping started to feel off. At the time, Thiele was practicing with different meditation techniques, from silent retreats to one-on-one sessions with Zen masters, and he began developing an almost spiritual connection to his bees. By trying to “perceive their needs,” he says, “it was almost like realizing I had a new sense that I did not know before.” Soon, he feared his bees were not living in a way that matched their instincts.

But when he turned to scientific literature to learn more about how honey bees live in the wild, he realized that it is an almost non-existent field of knowledge. “Most of our studies are conducted on captive bees,” he says. “It’s like if all we know about lions was based on studies of lions living in zoos.”

In the 1990s, when the notorious Varroa destructor parasitic mite first started devastating hives throughout North America, Thomas D. Seeley, a professor of biology at Cornell University, did a study on the wild honeybees of North America. Surprisingly, the wild honey bees living in Arnot Forest, a 4,200-acre patch of pristine forest near Ithaca, New York, had adapted to the mite much better than their human-held cousins. Like Thiele, Seeley also found that there was a huge lack of wild bee knowledge. In his recently published book, The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the Wild, Seeley has helped fill in this gap. Many of his findings, based on observation of wild bee colonies in Arnot Forest, echo Thiele’s thoughts.

For example, one of the first things that Thiele questioned about conventional beekeeping was hive location. “Many hives are kept at ground level,” he says. “But bees’ instinctual preference is to live 20 feet off the ground.” Seeley reported the same observation in his book, explaining that wild bees build nests far from the ground, probably to prevent attacks from bears and other predators, and to avoid being covered in snow during winter.

Next, Thiele started to question beehive density. “In the woods, hives have a capacity of around 40 liters and have at least 350 yards of space between each other,” he says. Most beekeepers host many more bees in more cramped spaces, with man-made hives designed with a capacity of around 160 liters and nests placed next to each other. As Seeley points out, the high density and large size of man-made colonies are designed to boost honey production, but perform poorly at containing disease. That’s partly why wild colonies proved more resilient to Varroa infestations, since mites can’t disperse as easily in roomier environments.

Most beekeepers in North America keep bees in Langstroth hives, a sort of bee condo made of piled-up boxes with removable frames. Thiele thinks that many aspects of its design are not suited to bees. Bees communicate key information about nectar locations with a ‘waggle dance’ which sends out vibrations across the hive. Such vibrations travel best at a frequency of 250 Hertz. But according to Jurgen Tautz, a biology professor at Julius-Maximilian University in Wurzburg, Germany, in order for such internal radio to operate smoothly, hives need to contain cells with a five-millimeter diameter. Thiele notes that most commercial beekeepers use frames with far larger cells to increase honey production, thus hampering internal communication. Plus, plastic materials can also slow down communication inside the hive, as plastic vibrates at a different frequency than organic material. “Bees send frequencies through the top part of comb cells,” Tautz says. “If this part is made of plastic, it has disastrous consequences for bees’ communication.”

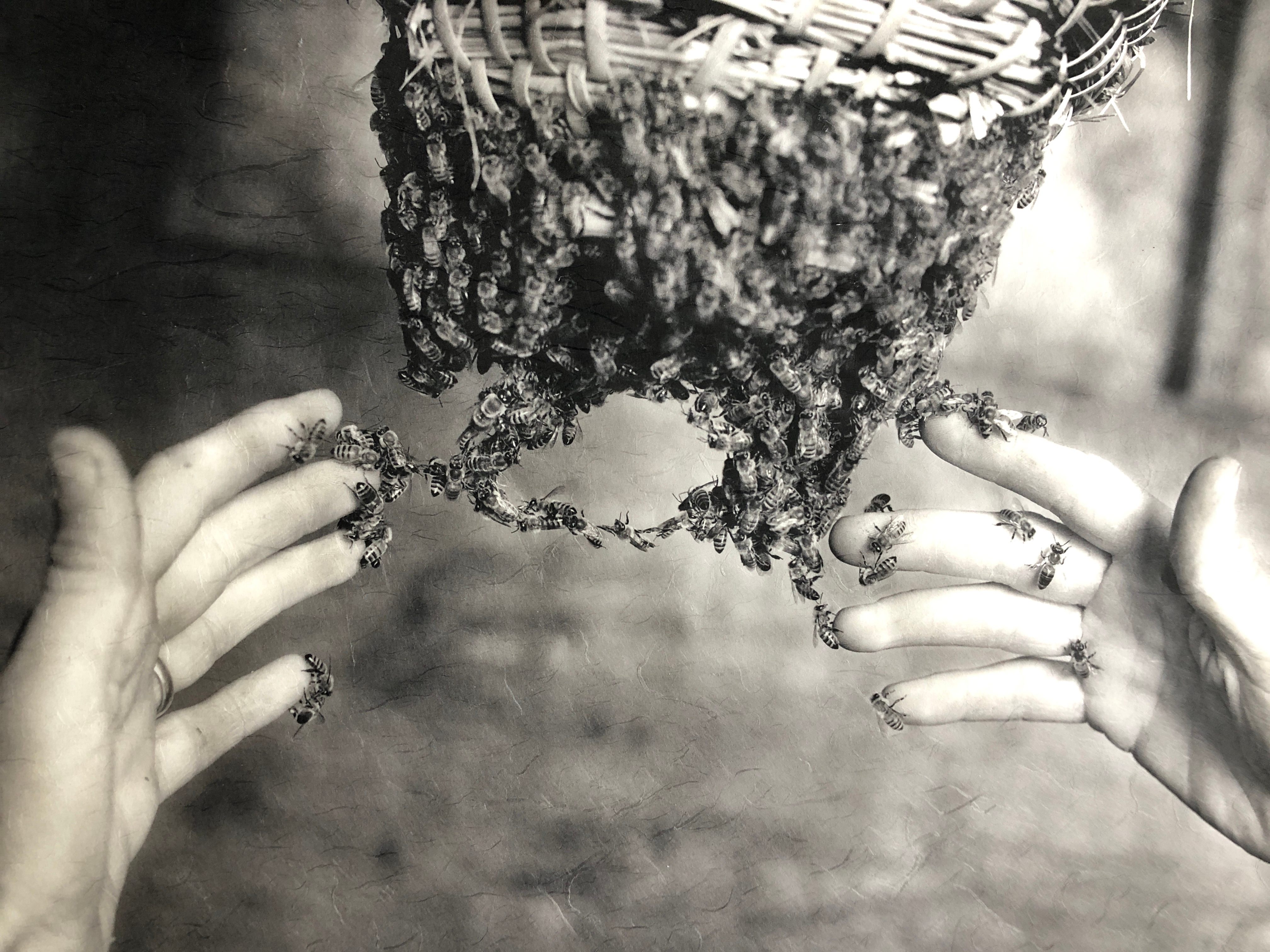

Over the past 20 years, Thiele has interacted with bees as much as possible to observe them, even working without the traditional protective gear. “It’s easier for us to understand mammals because they have eyes,” he says. “But you can get bees the same way if you let go of the fear of being stung.” When talking about his bare-handed work with swarms, which has attracted many admiring comments on YouTube, his voice becomes emotional, like he’s talking about a loved one. “It’s like feeling someone’s hand,” he says. “It’s such an intimate touch.”

On top of being a deeply enriching experience, his connection to bees helps him understand how to improve their lives. When setting up log hives high up in trees, he only uses organic materials such as ropes and wax. He models their entrances on natural nests, placing a small piece of comb by the opening and coating it with a tincture made of propolis, an antibacterial resin produced by bees to seal openings in the hive. “For them, it smells like home,” he says. Thiele estimates that his rewilding projects usually lead to a 50 percent increase in colony population. By comparison, Seeley notes in his book that thousands of commercial honeybee colonies report mortality rates of around 40 percent.

With urban beekeeping on the rise, Thiele thinks it’s crucial to inform the wider public about the importance of creating healthy bee habitats. “Some urban beekeepers act from a good place,” he says. “But they do more harm than good.” He gives the example of what he calls “packaged bees,” cheap and easy-to-assemble hives that are trending among amateur beekeepers. “They are built with toxic materials and with too much density,” he says. “Often bees get sick and end up spreading disease to local wild bees.”

Indeed, much of the problem with bee repopulation comes from systemic threats at the local level. Bees fly in an estimated range of one to two miles from their hive in search of nectar, so everything that they encounter on the way is potentially damaging. “All it takes is one farmer using pesticides one mile down the road and they are at risk,” Thiele says.

That’s why he advocates for the creation of protected local landscapes where bees can flourish, or “locapiaries,” where everyone would commit to practices that protect bees. That means creating hives with natural materials, avoiding pesticides that are harmful for bees, and preventing unhealthy proximity between hives. Going forward, Thiele hopes that this approach will become standard. He cites a recent case in Utah where lawmakers discussed a bill that would prohibit commercial beekeepers from installing an operation within a two-mile radius to another colony. “That gives me a lot of hope for the future,” he says. “But we need to act now.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook