The Winemaker Championing America’s ‘Foxy’ Grapes

Kate MacDonald wants to restore Cincinnati’s place as the birthplace of American wine.

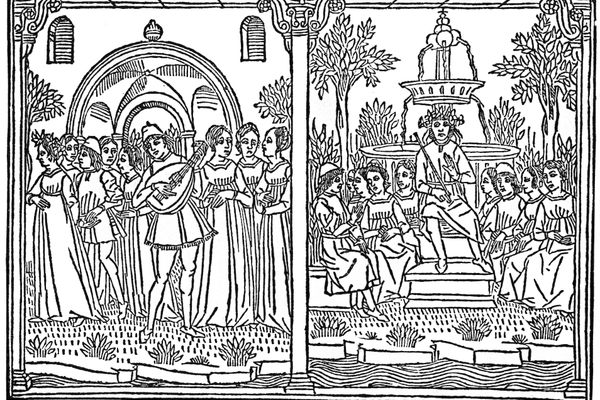

In 2013, Kate MacDonald was working in Napa Valley when she made a pair of discoveries that upended the traditional winemaking career plan she had so carefully plotted. First, as she read Thomas Pinney’s A History of Wine in America, she learned that her hometown of Cincinnati was, in fact, the birthplace of America’s commercial wine industry. In the 1850s, the city was the country’s largest grape-growing and winemaking region, thanks to the efforts of a wealthy businessman, Nicholas Longworth, who shipped his critically acclaimed wines across the country and overseas.

Equally surprising, Longworth found worldwide success using the lowly Catawba grape, an American native variety deemed unappealing and inferior by the wine establishment of the 1800s—and of today, too.

Inspired by her city’s lost wine heritage and Longworth’s unconventional choice of American grapes, MacDonald decided to gamble on bringing winemaking back to Cincinnati and proving—as Longworth had—that American grapes, especially the hearty Catawba, could produce high-quality wines. Today, she’s serving those wines at her Cincinnati winery, The Skeleton Root.

“When I was starting my journey with The Skeleton Root, I think most winemakers and growers thought I was nuts,” she recalls. “But once I became aware of the legacy and read about the classical style of wines Longworth produced from American grapes, I was hooked. It became a calling of sorts to try to resurrect them.”

To know MacDonald is to know she thrives on trailblazing. She began her professional career as one of few female engineers in supply chain management for the aviation manufacturing industry. As her engineering work took her to wine capitals, she became obsessed with wine and, while living in the wine-rich Finger Lakes region of New York, began experimenting with home winemaking. She decided to leave the status and security of her engineering position for the unpredictability and satisfaction of winemaking. Now she’s going against the grain again by championing American heritage grapes.

“It’s actually been motivating to me to know there’s a bias against American grapes,” she says confidently. “I love a challenge. I wouldn’t be in this business if I didn’t.”

MacDonald believes one source of the longstanding bias against American wine grapes is unfamiliarity with their flavors. America’s wine pioneers—mostly European immigrants—brought cuttings of European noble grapes (think Pinot Noir and Cabernet Sauvignon) to establish vineyards in the United States. This was what they knew, and wines made of native grapes tasted different and were deemed of lesser quality. As early as the 1600s, wine experts criticized American-native grapes for their “foxy” or “musky” smell—an assertion that is still made today and makes MacDonald indignant.

“I’m very put off by this term and have found few people who know what it means, although it’s thrown around commonly with these wines,” she says. “There can be a unique smell to wines produced from these grapes; however, I don’t find them musky or anything negative, for that matter. They are unique in their own right and are aromatic and beautiful, if produced well.”

Despite the bias against them, American grapes were grown and made into wine in the U.S. and even in Europe around the mid-1800s. In Cincinnati, Longworth replanted his vineyards with Catawba grapes, after finding his European vines did not grow well. Around the same time, Europe suffered the Great French Wine Blight, as an insect accidentally harbored on steamships across the Atlantic wreaked havoc on vineyards. When vintners realized that American grape vines were immune, they were able to save Europe’s faltering vineyards by grafting them onto American rootstocks—but not before experimenting with American-European hybrids. Unfortunately, only a few remain today, largely due to the opposition of the French government, which banned the hybrids and American grapes to protect the country’s vaunted wine industry. In the U.S., the Civil War disrupted Cincinnati’s thriving wine scene, and the temperance movement and Prohibition stymied American vineyards generally. When it ended, vintners, concentrated in California, planted Cabernet, Chardonnay, and other European grapes.

To change the wine establishment’s view of American heritage grapes, MacDonald believes her advocacy must begin with high-quality products. So, in 2014, she set out to replicate Longworth’s popular dry Catawba wines, which he had spent decades perfecting. Since his varieties disappeared after his death in 1863, MacDonald faced the hurdle of producing a wine she had never tasted.

She started by studying his meticulous notes, vintage reports, theories, and documentation in old books and articles from the Cincinnati Historical Society’s archives. Then MacDonald crushed a batch of regionally sourced Catawba grapes and aged them in neutral French oak barrels. When she tasted the wine after two years, she was concerned about its aggressive acidity and wondered if it would ever mellow. But Longworth’s records indicated that he favored extended cellar aging, which is counter to common practice in modern white wine production. To MacDonald’s delight, it turned out he was right: After the third year, the wine took on a refined quality, which only improved after the fourth year, when she began serving it at The Skeleton Root.

The process resulted in still Catawba wine: low in alcohol, aromatic, light in body with prevalent acidity and many botanical notes, especially citrus fruits. Since then, the winery has produced a Pét-Nat sparkling Catawba, which is a crisp and fresh younger-release wine, using the Ancestral Méthode. Due to their natural acidity, both wines pair well with foods that coat the mouth, such as creamy or fried dishes. They’ve also been well received in The Skeleton Root tasting room and around Cincinnati.

For MacDonald, producing high-quality wines starts with ensuring the quality of the grape. She sourced the 2014 vintage from northeast Ohio since the Catawba, which grows well across the midwestern and southern U.S., is now minimally cultivated in Cincinnati. Meanwhile, she’s evaluating her own Ohio River Valley vineyard, just over the state line in Indiana, for its fitness to support Catawba vines and her strong commitment to natural, low-intervention winemaking. She also works closely with the growers in five different vineyards to source grapes for her other wine varieties.

“The vines are wise enough to give balanced fruit if they’re given the right site, the right soils, and the right pruning methods,” she said. “I believe, as farmers, producers, and land stewards, we have an obligation to focus on raising plants that are the most sustainable. If we are working against Mother Nature, the excessive input required to keep up with those demands will be our demise.”

This is another reason MacDonald champions native grapes: She believes they may be the wine industry’s salvation in the face of ever-worsening threats from climate change. As conditions and seasons in established growing regions change, so will the viability of existing vines. Already, growing the most-popular European grapes far from their continental home typically requires a lot of irrigation, fertilizer, and pesticide. In contrast, native grapes are adapted to their environment, and MacDonald notes that American native grapes are particularly hardy, as they tend to adapt to changing weather patterns and climate extremes.

Ultimately, changing hearts, minds, and attitudes toward wines produced from American native grapes depends on market awareness. Although breaking through the barriers of the wine establishment may not come for many years, winemakers such as MacDonald are hopeful that Millennials are more curious and open than older drinkers, and have yet to fully develop their palate and commit to specific varieties.

“Millennials are an important customer group for us,” MacDonald says. “They’ve been avid supporters of the wines we produce from American grapes.”

MacDonald is also hopeful about the wine industry’s gradual evolution, marked by an acceptance of and appreciation for lower-input wines through the natural-wine movement, which promotes minimal use of chemicals and additives.

“There are beautiful wines coming from all corners of our country,” she says. “I’m starting to see an embrace of new wine regions producing wines from lesser known and appreciated grape varieties. It’s turning out to be an exciting time.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook