Meet the Women Behind the Heritage Food Revival

From Ukrainian pelmeni to Appalachian fried fish, these innovators are drawing on generations of culinary wisdom.

THIS ARTICLE IS ADAPTED FROM THE MARCH 18, 2023, EDITION OF GASTRO OBSCURA’S FAVORITE THINGS NEWSLETTER. YOU CAN SIGN UP HERE.

This Women’s History Month, Gastro Obscura is celebrating some of the women chefs, restaurateurs, and entrepreneurs drawing on generations of culinary knowledge and tradition in innovative ways.

From the duo who launched their pop-up during the height of the pandemic to a grad student who started a plantain empire while finishing her doctorate, the following visionaries use food as a powerful vehicle for storytelling. While all of these businesses were born and based in the United States, their roots encompass influences from East Africa to Eastern Europe and beyond.

Each of these interviews has been edited for length and clarity.

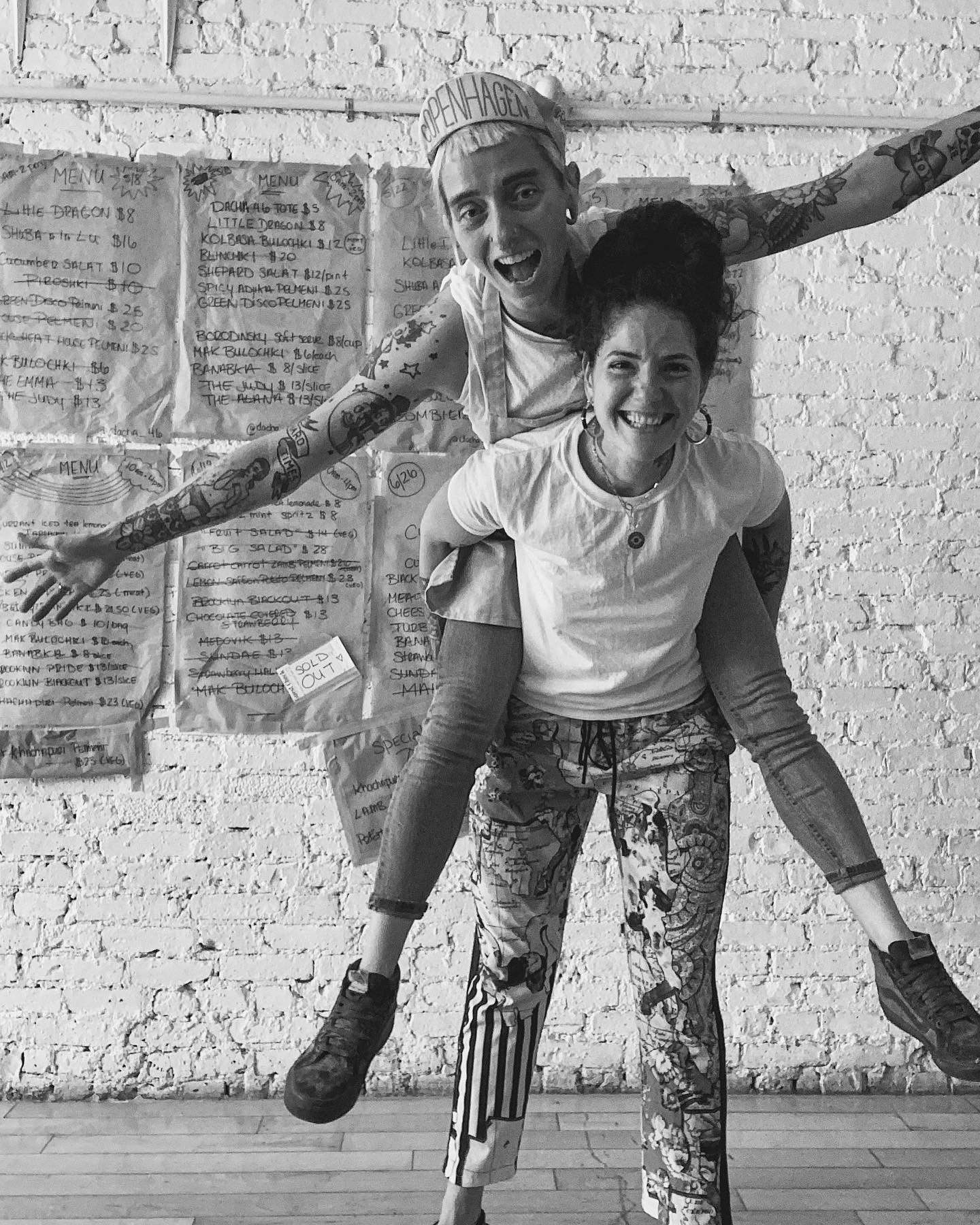

Jessica and Trina Quinn, co-founders of Dacha 46

Restaurant industry veterans Jessica and Trina Quinn first started selling pelmeni and other Eastern European–inspired dishes out of their Bed-Stuy apartment during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dacha 46, named after the Russian word for a welcoming second home and 1946, the year Jessica’s mother was born, has grown through a series of highly successful pop-ups.

Menus from Dacha 46 draw on both Jessica and Trina’s Eastern European and Irish heritage, with a few creative twists rooted in their years in professional kitchens. The pair are currently on the hunt for a brick-and-mortar home for the operation.

How did Dacha 46 come to be?

Jessica: COVID changed the landscape of restaurants overnight. Both Trina and myself had been working in this industry for many years and we were both at a crossroads with what to do. So we found ourselves at home, cooking comfort food, which for us, leans more towards my background, which is Eastern-European Jewish. We were just drinking wine, hanging out with our cats, and making dumplings all day long.

Could you walk me through the origins of some of your signature dishes?

Jessica: My dad is from Ukraine and my mom is from Riga, Latvia. They both immigrated here in the early ’80s. Some of my siblings were born there; I was born here. I grew up heavily entrenched within the culture. Both my parents are Jewish. The practice of tradition and obviously food within both the Eastern European and Jewish background is the focal point of everything in my family. I think that what we do [at Dacha 46] is a strong interpretation of these traditional dishes. There’s definitely a couple of dishes where I didn’t want to mess with them because they’re perfect as they are.

With our pumpkin spice honey cake, I was cracking up when we put that on the menu because I was like, my family would be dying right now. This is bastardization in its finest form. But at the same time, it’s fun and it’s playful and it doesn’t take itself too seriously. Neither do we.

What do you hope people take away from Dacha 46’s food?

Jessica: A lot of these dishes started with me recounting a memory. I grew up eating medovik. I grew up eating pelmeni quite often, like most Eastern Europeans do. The two of us are a same-sex married couple and we’re not exactly the most traditional sort of family unit. So we take these concepts and try to figure out how to evolve them. They’re a reflection of who we are as a business, as a couple, and as a family because that’s very heavily steeped in what we do.

Trina: What makes Dacha 46 so special is these dishes are made by our hands. They’re made from our perspective, through our lens and our experience. Jess was very distant with her culture for a long time because she didn’t feel like she had a place in it. When we first started dating, I didn’t even know she was Eastern European for almost a full year.

The biggest experience for Dacha is that we are creating a space for people that also feel excluded from spaces within their own cultures. By creating this business, it’s also paving a way for people to feel included and a part of that conversation, to celebrate themselves and the food and the culture they have every right to be part of.

Rachel Laryea, founder of Kelewele

After leaving a career in finance to pursue a dual Ph.D. in African-American Studies and Socio-cultural Anthropology at Yale University, Rachel Laryea found herself wanting to create a business of her own. Inspired by the culinary traditions of Ghana, she launched Kelewele, a New York–based pop-up selling ice cream, chocolate cookies, and other vegan desserts that all revolve around plantains.

Since closing her brick-and-mortar Brooklyn location, Laryea has been preparing for the publication of her first book, Black Capitalists, and working to transform Kelewele into a national brand available in supermarkets. Until Kelewele cookies start popping up at your local store, they can be ordered wholesale online.

Why plantains?

I have a plantain love story of my own. My family is from Ghana in West Africa, and plantains are a staple. Kelewele, long before was the name of my business, was and is the name of a popular plantain street food in Ghana. It’s basically diced plantains, marinated with spices and ginger, fried and often served with groundnuts. My mom would make me kelewele from time to time as a treat. As I got older, plantains had different levels of significance for me.

As an undergrad at NYU, I was always looking for affordable meal options. And so plantains became, yet again, something that I relied on because you can get them for around four for a dollar. In Harlem, I would often go to the Schomburg Center for lectures, and I could get them on the corner from the market sellers. Wherever there were communities of color, I could find plantains.

When did that love story morph into a business?

I had this lightbulb moment of thinking about plantains as a medium for culture. I can be West African. The next person can be from Latin America or the Caribbean, and we all have a shared familiarity with plantains, and we prepare it differently in our own kind of cultural customs.

I realized when I would talk to people about plantains, very quickly, the conversation would get to memories about a mom or a grandmother making somebody plantains or a particular plantain dish. It would evoke these feelings of belonging and memory and community.

What is your relationship like to Ghana these days?

Both of my parents were born and raised there. Soon after I was born, I actually lived in Ghana [for some time]. Ever since, I’ve been back and forth and definitely call Ghana home.

Over the last few years, I’ve been really intentional about doing things within the community in Ghana to also grow the business and share the message there. I’ve just been trying to build out this transatlantic connection. All of our operations are here, but I have plans to definitely do more on the continent as well.

How does your experience as a small business owner influence your forthcoming book, Black Capitalists?

Oftentimes, just given the history of American capitalism, there’s this prevailing thought that only certain people can benefit from capitalism because we’ve seen that show out in the racial wealth gap that exists today. But the argument that I’m making is to consider that if we take just the tools of capitalism, we can apply that within marginalized communities to rethink the role that we can have within it.

Ashleigh Shanti, chef/founder of Good Hot Fish

After leaving her post as chef de cuisine at Benne on Eagle in Asheville, North Carolina, in 2020, this James Beard semi-finalist set out on her own. Since then, Ashleigh Shanti has been hosting highly successful pop-ups, which draw on her childhood in coastal Virginia, her family heritage in Appalachia, her travels in East and West Africa, and beyond.

Currently, Shanti is working on her first cookbook and preparing for the opening of her restaurant Good Hot Fish in Asheville later this year.

Where did your interest in food stem from and how did that lead you to fine dining?

Like a lot of girls who grew up in the South, I found myself at the knees of my mom and my aunts and my grandmother when she was around. The kitchen was a very integral part of my upbringing. It was the gathering place. My mom can cook the best pot of greens I’ve ever tasted.

My parents are very much intellectuals and big on education. It was a big surprise to my family when I decided to go into the food space. I think mostly because a lot of us often equate service and hospitality with servitude. Throughout my career, I can certainly see where their concerns were valid. I think a lot of Black women will say that we do have to work a little harder to gain any sort of recognition.

My professional experience early on did not necessarily reflect the warmth of my grandmother’s kitchen, but by learning these amazing techniques, going to culinary school, and being on the line, I was able to put the food of my upbringing on a platform.

I still pride myself on the food that I put out [at Benne on Eagle]. It was just this confirmation that while this food can be seen as so humble and not necessarily deserving of a platform, that isn’t necessarily true. There is a place for all cuisines, I think, in the culinary world.

What culinary traditions have influenced your work?

My maternal side is from southwestern Virginia, and the food that they cook is very much Southern Appalachian. Being in [Asheville] brought up those nostalgic feelings of my great-grandmother’s food, of her making hominy and her stringing britches and doing all of those things that are so specific to Appalachia.

This is an entire food region that is so unique from any other region in the South. We have a bounty of wild foods that grow here. The agriculture is rich and diverse. It’s a place where the food kind of speaks for itself. It’s just so easy to elevate something as simple as a sweet potato that grows in this amazing mineral soil and has all of these flavors of chestnuts and molasses.

I’m originally from Virginia Beach, so there are a lot of coastal Southern influences in my cooking. Four generations back, I have family in Sierra Leone, in West Africa, and ensuring that everything that I do in my cooking honors that and speaks to that is also really important.

I spent a gap year in Nairobi, Kenya. I was incredibly inspired by the cuisine there and discovered things like sukuma wiki, which reminded me so much of my mother’s stewed greens. Finding those parallels are so cool to me.

What inspired your upcoming restaurant?

Good Hot Fish is not only a nod to my coastal Virginia upbringing, but also to the fish camps of this region. There’s still fish camps around [Appalachia], but they’re kind of a dying breed, sadly. There was a time when [people] in this region would gather more or less weekly. You’d put fish in a refrigerated truck or in coolers and have a friend or a family member set up a camp where the fish was gutted and fried. Fried fish brings me joy. It makes people happy.

This would also happen with lake trout just fresh out of the river here in the mountains, where the first business that women in my family had was just selling bags of fried fish in paper brown bags.

My dad often tells the story of my aunts, my great aunts, and my grandmother just going through their communities and yelling, “Good, hot fish! Come get your good, hot fish!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook