One Man’s Quest to Preserve the World’s Smallest Oil Refinery

The dusty, rusty site in eastern Wyoming is a rare relic of the 20th-century petroleum boom.

The world’s smallest oil refinery sits on the side of the road just outside of Lusk, Wyoming, a windswept prairie town, population 1,558. A half a world away in Islamabad, Pakistan, its owner, Zahir Khalid, works to keep the tiny industrial site from literally blowing away.

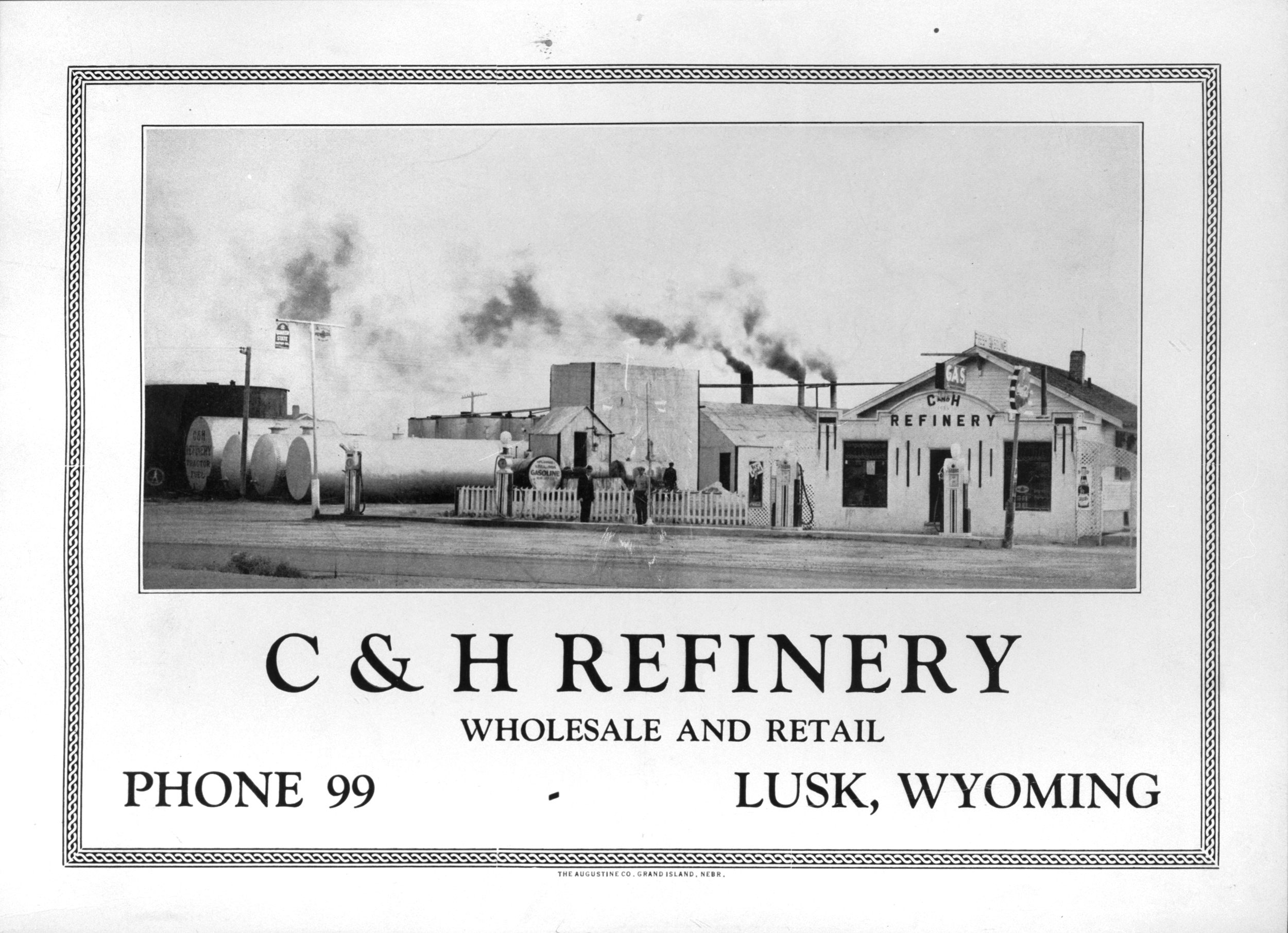

Khalid purchased the C&H Refinery in 1998 after learning it was for sale on an early Yahoo chat room. A devout Muslim, Khalid has the military bearing and discipline from his former life as a fighter pilot, and the persuasive charism of a wheeler-dealer businessman. He initially saw the refinery as a chance to buy into the American oil industry, but it was a classic case of caveat emptor—buyer beware. The refinery had not produced anything but local resentment and rust for years.

Khalid flew from Pakistan to Denver to see the site before he finalized the purchase. The owner, a retired oilman, picked him up and drove him four hours north, where the contrast with the urban bustle of Islamabad terrified him. “I was afraid to see the empty plains with no humans in sight,” Khalid said. “I was thinking that if this man leaves me here, how will I ever get home?” The refinery struck him as little more than a pile of industrial junk, yet he felt he had come so far. He paid cash and trusted that the future would make itself clear.

Once he adjusted to the emptiness of the prairie, Khalid made himself expert in his purchase. Roy Chamberlain and James Hoblit, two working class oilmen, built the refinery in 1933 and named it after themselves—C&H. Wyoming holds about 2.3 percent of America’s known oil reserves today, ranking between California and Louisiana as the eighth largest oil producing state. The first oil well was drilled in 1884, a time when independent oilmen came West seeking their fortunes away from the eastern oil scene dominated by Standard Oil. The Teapot Dome bribery scandal of the early 1920s made Wyoming oil the focus of national news and sealed its reputation as a petroleum state.

In the Depression, tiny refineries popped up across the oil regions as enterprising people sought to make the most of what they had. Chamberlain and Hoblit scrounged parts for their Lusk project from defunct refineries around central Wyoming, unintentionally creating something of a living history laboratory for today. For 45 years, C&H Refinery provided heating oil, gasoline, and a handful of jobs for the people of Lusk. It changed hands but kept running until 1978. After that it was shuttered for 20 years, until Khalid bought it.

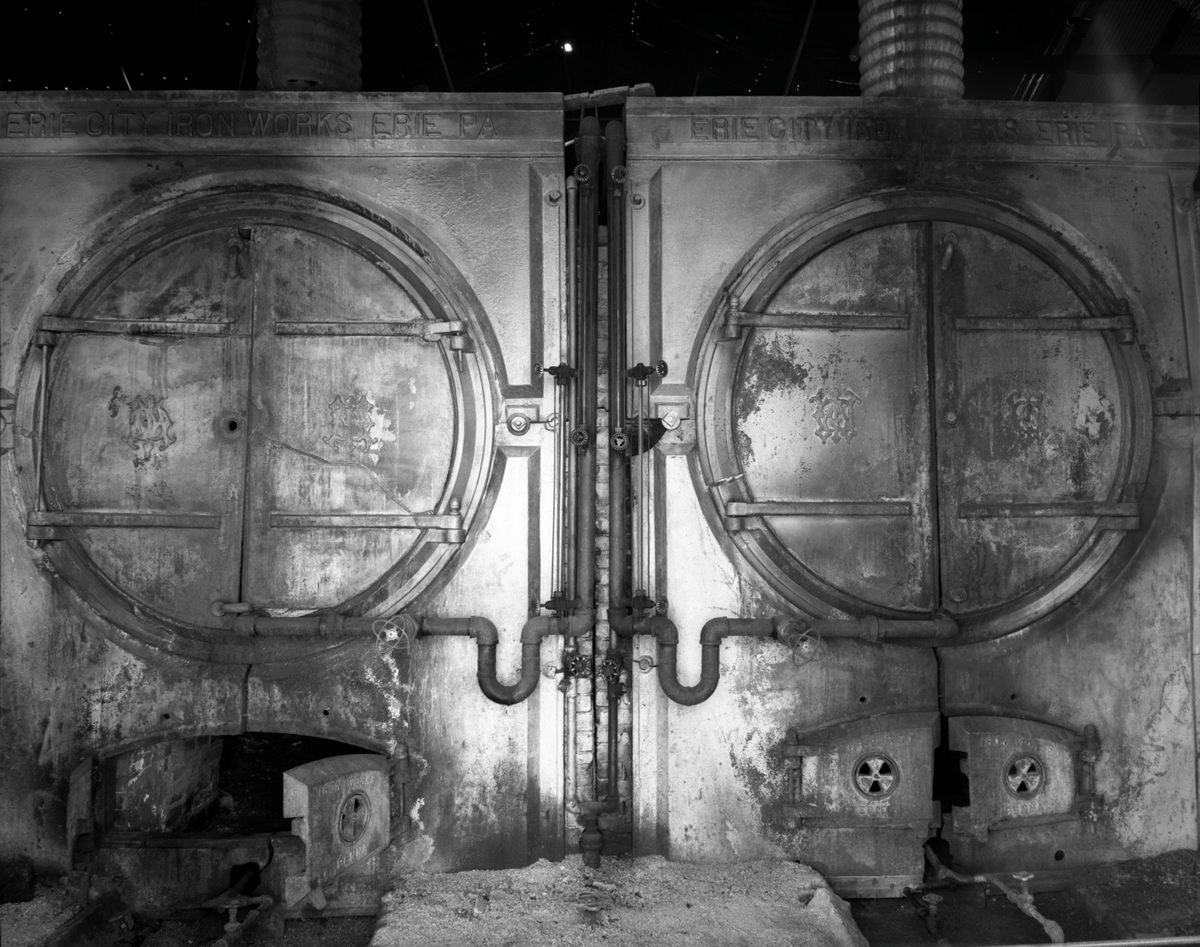

The refinery itself is a compact tangle of pipes and tanks, towers, and boilers, all visible from the road. Built to be operated entirely by steam, the center of the operation lies in a metal-sided building that houses two historically important stills, industrial relics that predate the state of Wyoming. Today, the site contains the original Spanish-style refinery office, a dozen salvaged steel storage tanks, and a building housing the heating elements for refining. In summer, tumbleweeds, and tinder dry grass make the refinery district look like the back forty of many ranches. In winter, the metal shack blocks the wind and concentrates the odor of fuel, dust, and rust. It smells the way industrial America used to smell.

“It is a graveyard of history,” Khalid said, gesturing at the rusty tanks during one of his many visits to Lusk.

In the early years, Khalid was indefatigable. He made annual trips to Wyoming. With the dedication of some local oil workers, he got the refinery working. That earned it recognition by Guinness World Records as the smallest operating oil refinery at a capacity of 190 barrels of crude a day. Khalid documented the history of the site with the help of local and industry historians, and it was granted a spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fairly quickly, Khalid saw that the historical value of the site exceeded its potential as a commercial refinery. Now, he hopes to repair the site so it is attractive and safe for visitors. Khalid would like to restore the office building and turn it into a museum with a café. He also envisions enclosing the stills and boilers in glass. He wants people to be able to see in, but to protect the works from the elements “so that we don’t lose the black, smoky feel of it,” he said.

“This is important heritage, and we need to save it,” Khalid said. Lusk is miles off the beaten path, but he imagines school field trips to learn about the role oil played in building America and tourists road tripping to see his tiny marvel.

Local support for preserving the industrial site at the edge of town is mixed. An oil field worker named Carmine Girone has worked to shore up its rickety buildings, replacing metal siding, screwing down panels that flap wildly in the wind and painting tanks and towers so the site looks less neglected. With Khalid in Pakistan its fairly thankless work and Girone is frustrated at the pace of Khalid’s investments in the site. Still, it was Khalid’s energy and independent mindset that drew him to the project. Before he met Khalid, Girone said, he felt, like many others in Lusk, that the refinery was a blighted mess that should be torn down. “Then, I looked at it with Zahir, and I started paying attention to other historic sites around, and I thought, ‘Yes, this can be a historic site that puts the rest to shame,’” he said.

Like Girone, Fred Chapman, a Wyoming-based archeologist who teaches at the University of Wyoming, was impressed by Khalid’s commitment to saving a piece of the state’s history. Chapman helped prepare the application for the National Register of Historic Places, took students to study the refinery and lobbied for preservation of the site.

The site’s connection to history beyond Lusk also intrigues Chapman. The distillation equipment at the heart of the refinery—two large brick and steel structures—have been salvaged and repurposed time and again and they are rare surviving examples of the earliest era of American oil innovation. “Those stills are unique—there’s nothing like them anywhere in the United States,” Chapman said.

The twin stills look like brick furnaces with steel doors that meet vertically, in the middle. Inside, they are a honeycomb of pipes feeding across a hollow space. The words “Erie City Iron Works” arc over the top of each still door. But who were they made for? How did they get to Wyoming? Erie City Iron Works was a major foundry located 40 miles from Titusville, Pennsylvania, where Edwin Drake drilled America’s first oil well.

Susan Beates, the historian and curator at the Drake Well Museum and Park in Titusville, Pennsylvania, believes the stills in Lusk were manufactured between 1880 and 1900. “This is probably one of a very few refineries left intact that contains technology from the late 19th and early 20th century and possibly the only Erie City Iron Works stills in existence,” Beates said.

Khalid is adamant his stills were manufactured earlier—perhaps as early as the 1860s—for one of the first modern refineries to handle Pennsylvania oil. But he sees more than technological history in his refinery. He sees a share of American glory days.

Sitting around the dinner table one night in Lusk, Khalid, Girone, and Khalid’s son-in-law were talking about a war-time newspaper advertisement paid for by the C&H Refinery. The ad featured a sketch of four American aviators at sea in a rubber life raft. Their plane has been shot down. The ad called on people to drive less so that rubber could be used to support the war effort and not for civilian car tires. The image of his refinery supporting these American pilots resonated with Khalid. “It is such an attractive ad,” he said. That the refinery would encourage people not to use its product is a sign of American selflessness. “It shows such patriotism,” he said.

For Khalid, the micro-refinery embodies the power of post-war America. “I feel this pride in what America did, in that great victory,” Khalid said. “I feel I share that because I own this property, this refinery, here in America.”

As the world anticipates a post-fossil fuel age, Khalid sees petroleum as a modern miracle the world will never truly run without. “When fossil fuels are in the past the C & H Refinery will gain more importance as it represents the most important commodity that changed the world more than any other substance.”

The last 18 months the global coronavirus pandemic has done what even 9/11 could not: prevented Khalid from traveling to Wyoming. At home in Islamabad with his wife, Tahira, Khalid, now retired from business, collects gemstone and mineral samples, and is working to display his collection in Islamabad. He also stays in touch with his American friends and continues his research to prove the connection between his stills and the earliest American oil industry.

He has long hoped that America’s oil giants might recognize the historical value of his refinery and join him in his efforts to create a place to remember oil’s role in empowering America. Archeologists, artists, and representatives from a refinery in Cheyenne have come to visit the site but left without committing resources to the fight for its future.

Sometimes he gets frustrated when he feels America doesn’t share his love of its own history. He has considered taking the stills to Pakistan, but he knows that without context, they would just be old vats. “That would be like taking the Statue of Liberty to China,” Girone said when Khalid gave vent to his frustration. “It wouldn’t mean a thing to them.” Khalid agreed and turned the future of his refinery over, as he often does, to his faith.

“When you are alone, you are not alone. Allah, God, walks with you,” he said. “Our job is just to make an effort. Destiny, we don’t know. Destiny is in the hands of God.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook