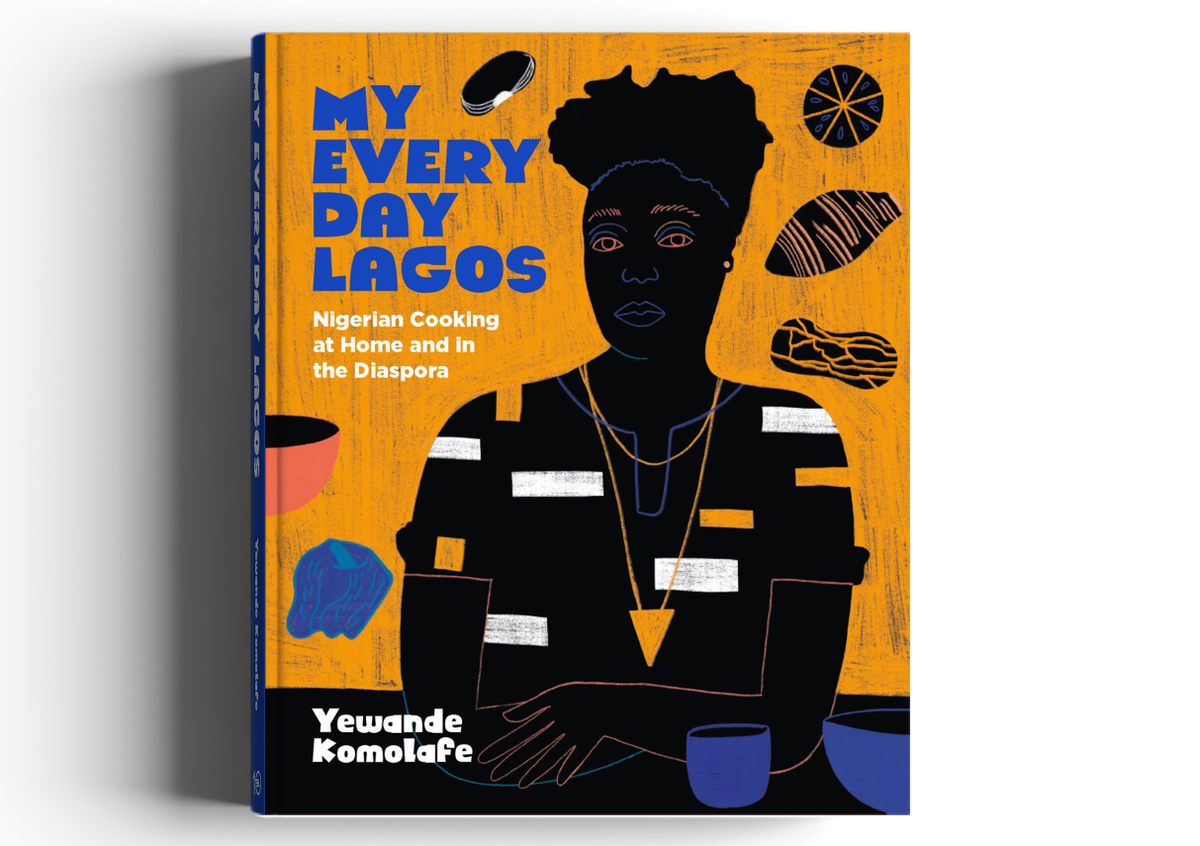

Yewande Komolafe Explores the Many Flavors of Nigerian Food

‘My Everyday Lagos’ is an uncompromising guide to this diverse city’s cuisine.

“Whenever you are in Lagos, the streets are never silent and never still,” writes Yewande Komolafe of the 15 million-person metropolis where she grew up. In My Everyday Lagos (available October 24), the Brooklyn-based food writer, recipe developer, and food stylist for The New York Times leads readers through the streets, markets, and homes of this city by the sea. After decades spent in culinary school, restaurant kitchens, and test kitchens in the United States, Komolafe sees Nigeria and its many varied cuisines through both fresh and deeply familiar eyes.

Komolafe cautions, “I implore you not to approach this cookbook from the perspective of an outsider.” Rather, she hopes readers will dive deep into the book’s delicious offerings, whether or not they already stock woodsy calabash nutmeg, rich ẹ̀gúsí seeds, and umami-loaded dried crayfish in their home pantries.

As a veteran chef and pastry chef, Komolafe has a gift for breaking down the technical aspects of recipes into precise, approachable steps. Whether it’s fermenting cornstarch for a soul-soothing breakfast or curdling unrefined red palm oil to lend a lustrous sheen to sauces, she confidently walks home cooks through the process.

A number of these recipes are slow food in the truest sense, built by carefully laying flavors over one another. But while dishes such as whole braised goat leg served with jollof rice or móị́n móị́n (celebratory parcels of steamed bean paste folded into water lily leaves), are a bit of a project, Komolafe encourages her readers to take the time to embrace each step in the pursuit of something truly remarkable.

Gastro Obscura spoke with Komolafe about the pleasures of home fermentation, her dinner parties in Brooklyn, and the search for the perfect bite.

Nigeria is so culinarily and culturally diverse. How did you go about whittling down which recipes to include and how to frame them?

While working on my [“10 Essential Nigerian Recipes”] piece for The New York Times [in 2019], there was so much more that I wanted to include in there. I thought of this book as an expansion of that project and as another opportunity to tell a deeper story and a more nuanced one.

Lagos was a great place to set the story because Lagos is a big city similar to New York. It’s full of people from all over Nigeria. So it’s one of the places where you encounter food from all different regions in one place.

The deeper I went, the more I realized that I was not telling the story of Nigerian cuisine. I think that’s a nice word, but I don’t know what it really means. In researching the book, I realized I’m telling the story of a bunch of different regions, and I needed to honor those regions and not put them under this blanket term of “Nigerian food.”

Instead, I say, this is Yorùbá food and this is Igbo food, or this is Northern Nigerian cuisine. When I started to break it apart like that, it really started to make more sense.

Was there a weight in writing about dishes to an audience that might not know them and is experiencing them for the first time?

Absolutely. There was a weight, especially because the greater part of my culinary career has been in the U.S. I moved here as a 16-year-old. I went to college and then went to culinary arts school here. So as someone who has come up in a very Eurocentric way of defining food using Eurocentric terms, I also had to take a step back to examine the way I thought about things.

[I thought,] Oh, wait, our food doesn’t really fit into these structures as is. Is it my job to break it down and make it fit? Or do I just create an entirely new structure? And I arrived at the fact that I just need to take the structure as it exists in Nigeria. The people that understand it, understand it, and the people that don’t either do the research to be able to digest it or they don’t. Especially because this was my book, I felt very strongly that this was an opportunity to present the work as is.

The way that I think about recipes fundamentally changed while working on this book. I think it really went back to what it was before my training, before moving here. In doing this book, I really just discovered for myself personally what it means to be Nigerian, what it means to be Yorùbá, what it means to have grown up in that country.

You make a few suggestions for substitutions, but you really encourage readers to actually seek out the proper ingredients. Why do you think that matters?

It’s not about insisting on doing it one specific way, because no two houses cook the same. It’s more about honoring the stories behind the recipe. Honoring the fact that people cook this every day, honoring the fact that I’m not telling a new story; I’m telling a story that exists already. Nigerian food exists and it will continue to exist with or without this book.

So, yeah, I felt very strongly about not giving substitutes. I think that adaptation is definitely part of the immigrant process and the immigrant story. At first when I moved to this country and didn’t really know where to source dried crayfish, I would use dry shrimp.

But I don’t want to give in to that story that says our ingredients are difficult to source because people cook this food every day here in America, in Nigeria, in China, and across the world. Nigerians have immigrated everywhere. And we’re able to access our ingredients. We’re able to access our food.

Is there one recipe that really stands out as having a personal resonance?

During the pandemic, I got obsessed with making ògì, which is a fermented corn porridge. It’s something that I watched my mom do growing up, and I sort of forgot about it. Then when I started to go back to Nigeria after 20 years, I re-encountered her making it, and it was just the most beautiful process. It goes from taking dried corn that’s off the cob and soaking it in water. The corn gets all nice and plump and robust, and then it goes to a grinder. Usually in Lagos, you would take it to a community grinder where they just have an industrial machine that grinds whatever you bring to it.

I watched my mom every single time she made this dish. The technique is basically you soak the corn, you grind it, and then you wash it. And in the process of washing it, the starch grains fall out through a very fine mesh seed, leaving behind the husk, and you get this milky-looking liquid, which you ferment and then turn into a cooked porridge.

I love treating my fermentation as a pet. It makes me so happy to say, “I have some corn fermenting on the counter and I’m going to check it in a few days and see where it’s at.” It’s almost like a conversation with nature, and it’s so fascinating to me that it’s responding.

That process blows my mind every single time I do it. I’m like, Who figured out that you need to extract cornstarch from corn grain, and then you need to ferment it, and then you need to cook it for this very pleasing porridge at the end? I now make it in my kitchen in Brooklyn, and I’ve gotten to the point where I’m buying different-colored corn. So I’ve made a lavender ògì and I’ve made a millennial-pink bowl of ògì and I’ve made a yellow ògì.

My first daughter was two at that time. So we would make it and she would squash the corn with her little hands. It was the cutest, most intimate bonding moment when we were all scared about the pandemic.

I was really struck by the detailed primers on techniques like fermenting grains at home or pounding chiles, dried crayfish, and fermented locust beans into a flavorful paste.

I think that’s just me being a Virgo. It’s also being a chef, and coming from a chef background. I love getting really locked into the technical aspects and I feel like that’s the part of cooking I really enjoy. That’s where my eyes get all glittery.

I think that in a sense, I tried to tell the story of how I do it. It doesn’t mean that this is exactly how you do it. Do it this way, discover if you like it and then do it according to your preference. I want everyone who cooks from this book to know that they have autonomy, that their senses matter. If you take something that you cooked from the book and you don’t like it, change it up. Don’t put as much pepper, don’t put as much turmeric or whatever spice. I want people to make it as much their own as it felt like it was mine.

You have a section in the introduction about how working in food media changed your perspective. You write, “I began to constantly question whose food I was making. I didn’t see myself reflected in it.” Can you talk about that a bit?

I grew up with a mom who was a food scientist, so I grew up going to test kitchens [in Nigeria]. Recipes were almost like the language that she could speak through. In working on recipes with my mom, I felt like I really got to know her.

And then I moved here and I thought, I’m going to do it the cool way and go to culinary arts school. I don’t want to be a scientist. I want to be a chef. I want to sling knives. So I went to work in restaurants, where I met other immigrants like myself.

Then I got to food media. In test kitchens, I only saw white people in the photos and throughout the line, editors, food stylists, photographers. I was always the only Black person. It almost made me forget that my mom had this background in test kitchens as well. I grew up knowing Black food scientists and Black recipe developers and Black photographers.

There was a moment in my career when I looked around and I was like, Nobody looks like me. I never see Black hands in photographs holding food or eating food or Black people just having fun at a restaurant. It made me start to ask the questions like, Why don’t I see stories about Nigeria or immigration or any [food] stories that are not either French or Italian? It’s always about going to Paris and eating croissants. Who doesn’t love that? But I also want to see stories about being in Uganda and eating ugali.

I started to ask that question, like, why don’t I see stories where I see myself reflected? I go to Montreal every summer, but the places that would get covered in Montreal were never places that I would go to. There’s an entire French-speaking African population in Montreal, but that never got covered. And if I did see stories on immigration or people who looked like me, it was always told by a white person. But I was interested in stories that were told by people who look like me about themselves.

I want to see stories of people who look like me. I want to see Black hands holding a beautiful salad, or I want to see Black hands rolling out a kouign-amann because these stories do exist. It’s not because there’s a lack of these stories, but it’s just like the people in power are not interested in the stories now, for whatever reason. It just made me question whose stories are being told and who is telling the stories. Especially living in New York, you come across people from all over the world, so it doesn’t make sense that only one section of the world is being written about.

Before the pandemic, you threw a dinner party series called “My Immigrant Food is…” What was the genesis of that project?

Food is my way to explain the world around me. Food is my lens. At that time in my life, I hadn’t been back to Nigeria in 20 years. I hadn’t been back because I was undocumented. And it became a possibility after I got married. It opened up this world, but it also made me realize how distant I felt from it.

[The dinner parties] were really me exploring my identity. I wanted to understand what it meant to be Nigerian, even though I hadn’t been back. Am I cooking Nigerian food? Am I serving Nigerian food? What makes me Nigerian? These were kind of all the questions that I was asking myself. And I kind of arrived at the place where I’m Nigerian if I say I am. Not one thing defines my Nigerianness.

What was it like re-exploring and discovering your own homeland, but through the lens of someone who’s now a trained chef and professional food writer?

It just gave me more of an appreciation for my food culture. I think that I never thought it was worth examining because I always had it. Wherever I went, I was always Nigerian. Even though I hadn’t gone back in so long, Nigeria never left me. So I was like, Let me go learn how to make French pastries and let me work at this Momofuku restaurant and learn things there.

It was interesting to turn the lens inward. It was interesting examining my own food with the same lens of experience and realizing, say, when we layer shrimp with fermented locust bean and fermented corn, that is an excellent example of how to balance flavor. It just gave me a really great appreciation for the food of my culture because I’m able to understand the techniques. I’m able to understand how the food is expressed.

One thing that people would say about Yorùbá food is that it’s always spicy. But it takes a level of expertise to create spice but still have other flavors come through, to have spice and salty and a tiny bit of sweet and fermented and have all those flavors playing together in the same dish. The person on the side of the road [in Lagos] selling whatever they’re selling is a master of their craft.

That’s why I’m obsessed with creating the perfect bite in all my dishes. Because Nigerian food does this. The perfect bite is every bite. I love that I come from a food culture that is just so excellent in the way it balances flavor and texture and acidity, and there’s so much expertise that goes into it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook