How Alaskan Yup’ik People Are Reviving the Culture Lost to the 1919 Flu

After the pandemic erased a generation, putting the pieces of the puzzle back together.

It wasn’t so long ago that Yup’ik culture, in Alaska’s subarctic Bristol Bay, revolved around dance. There were dances of greeting, dance festivals, dances that went all along the river and into communities. These days, many, if not all, of these dances have been lost to cultural memory. “We don’t do that anymore,” says Arnaq Esther Ilutsik, the director for Yup’ik Studies for the Southwest Region Schools in Dillingham, Alaska. “It’s no longer practiced, because of the big flu epidemic.”

As an educator, Ilutsik has dedicated decades of her career to filling a long-standing cultural void, the one left after the so-called Spanish influenza swept across Bristol Bay in 1919, wreaking extraordinary devastation on the area and its peoples. She interviews Yup’ik elders, for instance, and transcribes and translates what she can to prevent knowledge from being lost entirely. Inevitably, holes emerge: She hears individual words she’s never heard before, she says, ”words that we don’t know, because we don’t have that high vocabulary fluency.” She jots them down, and tries to follow up where possible. “But it comes to the point where—well, we’re getting old, too.”

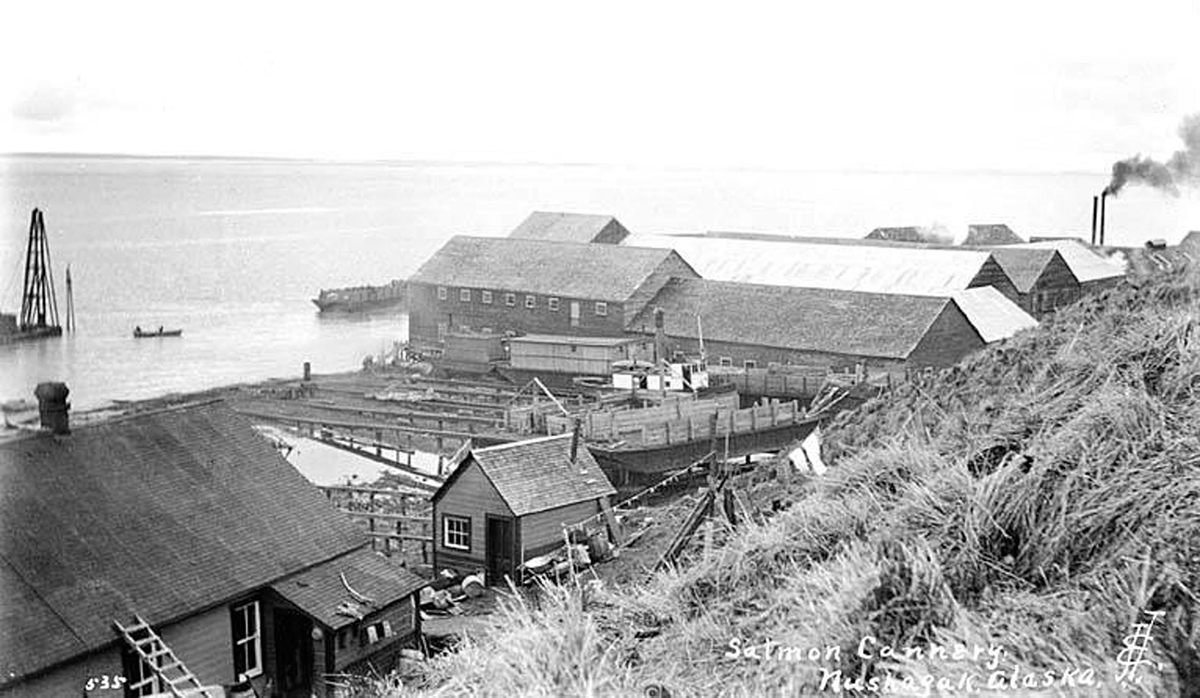

Over the winter of 1918, as outbreak after outbreak of influenza made its way through the United States and the world, the people of Bristol Bay were protected by isolation. Home to one of the world’s most productive salmon fisheries, Bristol Bay is beautiful, wild, and extremely remote. One 1920 account, by missionary Hudson Stuck, describes a bitter climate and sometimes desolate landscape. “Yet it is not without scenes of great beauty and even sublimity, and its winter aspects have often an indescribable charm,” he writes. “A radiance of light, a delicate lustre of azure and pink, that turn jagged ice and windswept snow into marble and alabaster and crystal.” But few people outside the Native community saw this icy beauty: From September to May, the area was naturally walled off by multiple mountain ranges and the frozen Bering Sea.

As the sea ice began to thaw at the start of 1919, says Alaska historian Katie Ringsmuth, the first fishing boats of the season arrived, and people started to gather once again. “That winter, people thought [the epidemic] was over,” she says. “They had shut everything down—the school, public gatherings and churches, and all of a sudden, springtime, they thought it was okay to come back.” By the time canners arrived from San Francisco to work the salmon fishery in May, people had already begun to succumb to the virus.

Accounts of how the flu arrived differ. Some sources point to a Russian Orthodox priest who held a large Easter service attended by many local people. Others suggest that the dates behind that theory don’t hold up to scrutiny, and it must have been some unknown outsider in the weeks that followed. Either way, by the third week of May, dozens had died. It would grow much worse.

In the mid-1980s, Harold Napoleon, a respected Yup’ik elder, spent nine years in prison after killing his four-year-old son in what he described as an “alcoholic haze.” While incarcerated, Napoleon wrote a powerful treatise about what his people had endured the past century, entitled Yuuyaraq: The Way of the Human Being.

Before Westerners came to Alaska, he writes, the Yup’ik were ruled by the same cultural practices and spiritual beliefs they had maintained for hundreds of years. Everything was prescribed: the relationships between individuals, the correct way to hunt and fish, every song and dance, every kayak and umiak. “When the Yup’ik walked out into the tundra or launched their kayaks into the river or the Bering Sea, they entered into the spiritual realm,” he writes. “They lived in deference to this spiritual universe, of which they were, perhaps, the weakest members.”

The arrival of Western explorers, traders, and missionaries in the 19th century disrupted these practices. At first, the Yup’ik continued to live as they had always done, resisting Russian efforts at colonization, but they were susceptible to wave after wave of disease that decimated their population. By the turn of the century, outbreaks of measles, smallpox, influenza, and other diseases had reduced the Native population of southwestern Alaska by more than a quarter. These successive tragedies both traumatized survivors and undermined their cultural practices. “In their minds, they had been overcome by evil,” writes Napoleon. “Their medicines and their medicine men and women had proven useless. Everything they believed in had failed.”

By 1918, the Yup’ik were a people in transition. “They still lived mainly by hunting and fishing, and sought out shamans to interpret the spirit world for them—especially when they were sick,” writes Laura Spinney in Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World. “But many now lived in modern houses, wore store-bought clothes and, in the Nushagak area, professed the [Russian] Orthodox faith.”

That winter of 1918 and 1919, as the flu moved across the world, Linus Hiram French, a cannery doctor employed by the Alaska Packers Association (APA), had imposed a quarantine on the region, restricting travel in and out of the villages, even as the region itself was isolated by ice and geography. As the spring came, and the flu appeared to be abating elsewhere, the restrictions gradually fell away. When it arrived, there was little to slow the contagion.

On May 19, an APA steamer arrived in Bristol Bay from Seattle. Aboard the ship was Shirley Baker, the federal Bureau of Fisheries’ warden, who later filed a report on what he saw. “The Government hospital was crowded with victims, and the whole hospital staff was sick with the disease,” he wrote. “The dead were lying unburied in their barabaras, and in many instances half-starved children were found in homes with the badly decomposed bodies of their elders about them.” For the next three weeks, he helped locals to bury the dead: “Many of the bodies were far gone in decomposition; ravenous dogs had been feeding upon them, and the conditions were too harrowing to narrate in this report in detail.”

Though millions all over the world perished due to the influenza outbreak, “more people died per capita in Alaska than anywhere in the Americas,” says Ringsmuth. Throughout the territory—Alaska did not become a state until 1959—Native communities were hammered. “Many didn’t have running water,” she says. “Culturally, people lived in very close proximity together. So you have a situation where when one person gets sick, then everybody does, and it moves through communities very quickly.”

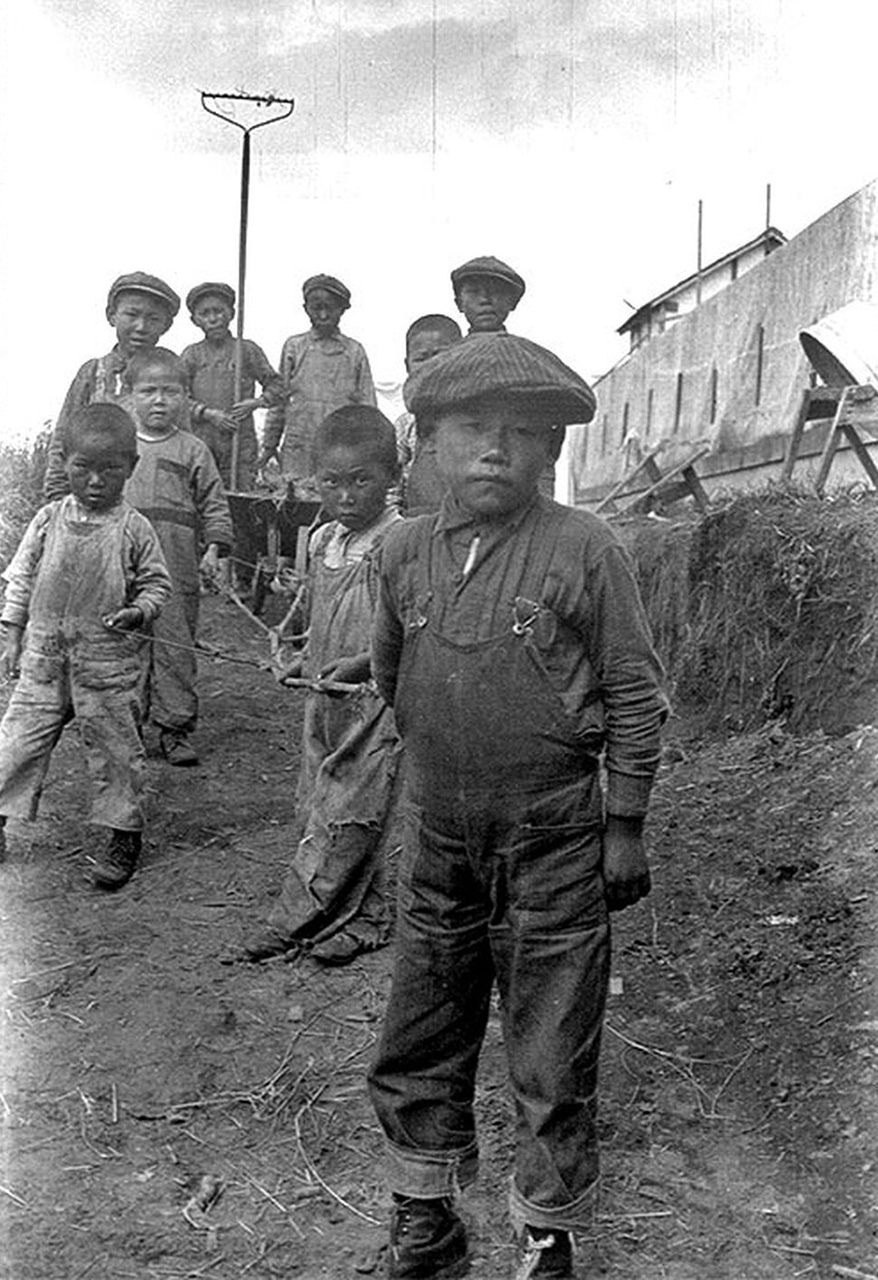

In Bristol Bay, the hospital was overwhelmed, with insufficient nurses and doctors to treat the scale of the outbreak. The sickness spread throughout the community, Ringsmuth says: “It was also the ethnic migrant workers, who worked in the canneries that were brought up. They got sick, too, and they were blamed for that, because of their race, and I think that helps us to understand the kind of racism that existed at that time.” These were essential workers, feeding the world, and many of them perished. “It’s also a story of complacency,” she says, pointing to a report made by the governor at the time. “He was furious with Congress, because Congress did not allocate enough funds to save Alaskans. Again, it was because they didn’t see Alaskans as humans, as Americans.”

Though three institutions did work to rescue the sick in Bristol Bay—the Coast Guard, the Bureau of Education Territorial Hospital, and the APA—there were numerous bureaucratic and practical problems, ranging from sick team members to insufficient vessels that could make it up the river to treat the sick in remote communities. Racist attitudes, including the quasi-phrenological belief that Native blood was somehow inferior for warding off disease, sometimes interfered with caring for highly traumatized, starving children.

It’s hard to know exactly how many people died due to the outbreak, though estimates of the total population loss are as high as 40 percent. In some cases, entire villages were abandoned after all the adults died, with children raised by relatives or in orphanages, without the languages or cultural practices that ought to have been their birthright.

Even a hundred years on, the 1919 influenza outbreak still feels very close, says Ilutsik. “I’m really concerned with COVID-19,” she says. “We’ve really tried to be really strong about who comes in and goes out—I myself grew up without any grandparents, because my parents’ parents both passed in the flu epidemic.”

Though she spoke the language with her parents when she was a small child, Ilutsik was placed in a white foster home for three years due to a tuberculosis outbreak. When she returned to her family, at age six, she’d forgotten a great deal, and the language was further suppressed in schools and other official settings. When she had children of her own, she opted not to speak Yup’ik with them. “My daughter understands why I never spoke Yup’ik to her, because it was a forbidden language. And so you have it deep in your memory that you don’t use that language.” Her own mother eventually helped her to pick it back up, though she says she’ll never have the fluency or cultural familiarity of previous generations.

“The big flu really devastated a lot of different cultural traditions and practices,” she says.

“They used to have a really strong kinship system. I grew up in a traditional home, but we didn’t really have any relatives around to reinforce different ideas and values.” When speaking to her father, a reindeer herder, she would be expected to pass questions on through her mother, even if he was sitting right there—a practice that’s long since been abandoned. “My parents, especially my mother, would always excuse me for my accent, because I didn’t know that proper way, the etiquette, the way to honor different parts of the family.”

Now, as a teacher of Yup’ik Studies, Ilutsik works to educate Native youth about traditional Yup’ik ways and language, in addition to instructing new Alaskan teachers on the region’s culture and history. “I’ve had no training in language preservation or how to build a program or that kind of thing, so it’s all new to me,” she says. High school students in the area can learn Yup’ik to replace foreign language credits, in addition to taking subsistence classes to learn about traditional foodways.

But it’s a challenge, especially when it comes to getting distracted teenagers to engage with their cultural heritage. Ilutsik has tried to look beyond teaching numbers and colors, and to the sharing and maintaining of the storytelling that has long been a critical part of Yup’ik culture. Here, the accounts relayed by elders are especially useful, as they paint a vivid picture of what once was. “We’re trying to put the pieces of the puzzle together,” she says.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook