How the Czech City Built on Shoes Reclaimed Its Past

Zlín is revitalizing its history on the heels of Communist rule.

When the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, the Czech city of Zlín found itself searching for an identity that many felt had been lost during the Communist regime, and before that, the German occupation. For many in the Czech Republic today, Zlín is synonymous with shoe-making, but for decades, this wasn’t the case.

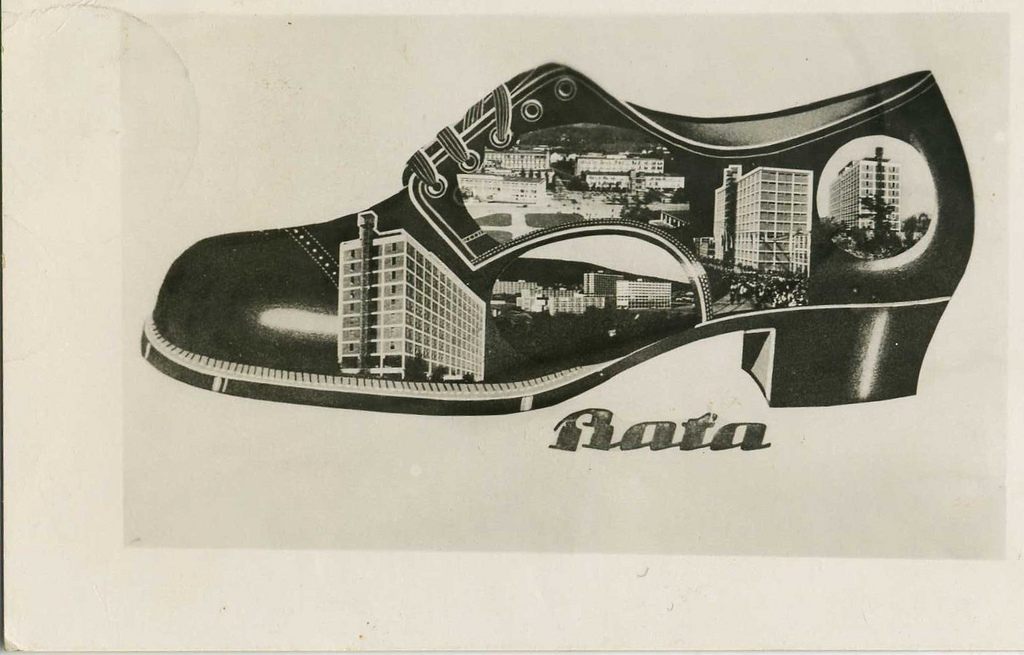

The modern city developed alongside and because of the Baťa shoe brand. After the Velvet Revolution, citizens of Zlín galvanized around the idea that their city should be built on shoes. In doing so, they kick-started a renewed interest in their town’s unique history, industry, and architecture.

In 1990, The New York Times summed it up: “Czechoslovaks want Thomas Bata, head of the world’s largest footwear company, to come home and help revive the shoe industry that his father created in the Moravian village of Zlín earlier in the century.”

Two notable results of Zlín’s efforts are its Museum of Shoemaking, which boasts a comprehensive collection of Baťa artifacts, and the Baťa Institute, which is housed in two converted factory buildings. The museum showcases both local heritage and influential designers from around the world, while the institute offers an educational experience and immersion in the town’s history.

The modern era of that history began in 1894, when Tomáš Baťa, along with his brother and sister, Antonín and Anna, launched the T. & A. Baťa Shoe Company, a small startup in a town of what was then 3,000 people. The company strengthened as a result of Tomáš’s study and implementation of mechanization techniques from around the world. And the timing was fortuitous: the T. & A. Baťa Shoe Company (also known as the Baťa Shoe Company or simply, Baťa) supplied the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I. Business boomed.

By 1922, Baťa had become the leading manufacturer and marketer of footwear in Czechoslovakia. During the time Tomáš Baťa served as Zlín’s mayor, from 1923 to 1932, the number of Baťa employees in Zlín grew from 1,800 to 17,000. The city’s population swelled right alongside the company, growing from 5,300 residents to 26,400. As the worker base grew, so did the need for housing and other facilities in close proximity to Baťa’s factories.

The architectural style that developed in Zlín was influenced by those factories as well. The same construction materials were used for both public and private spaces, blurring the lines between work and home. At the same time, the garden city movement (an urban planning philosophy in which self-contained communities are surrounded by “greenbelts”) played a role in the town’s layout. The hope was that those green spaces would help residents feel less penned in by the brick structures in which they worked and lived.

This era also saw the addition of a number of ambitious new structures in Zlín, built by Baťa architects., They include Baťa’s Hospital, (among the most modern ever constructed when it was completed in 1927), a sprawling movie theater with seats for 2,580, and Baťa’s Skyscraper, which served as the company’s global headquarters. For himself, Baťa commissioned the influential Czech architect Jan Kotěra to design a lavish villa. Today, it’s the headquarters of the community-oriented Thomas Bata Foundation.

In addition to bringing the world quality footwear, Baťa brought its employees excellent perks, introducing in 1923 what is believed to be the first employee profit-sharing program. Employees were thus not just workers, but individual entrepreneurs with a significant stake in the business beyond their own employment.

The company continued to grow after Baťa’s death in 1932. By 1939, when the German occupation began, Baťa had stores and factories in 38 countries and over 65,000 employees. The war itself hit Zlín in 1944, and nearly all industry was halted as infrastructure was destroyed. When Zlín was liberated by Soviet and Romanian armies in 1945, its future was uncertain. Baťa’s surviving relatives (and co-founders) had relocated to North America, leaving the town that Baťa built without a Baťa.

The new Communist regime took over management of Zlín and Baťa factories, nationalizing the company and even changing the name of the city to Gottwaldov, after the first communist president of Czechoslovakia, Klement Gottwald.

As the company continued to grow on a global scale, (at this point led by Thomas J. Bata, the elder’s son), headquarters moved to England and later, Toronto, Canada. The city of Zlín was in effect abandoned by the industry that had given birth to it.

It wasn’t until many decades later, after the Velvet Revolution, that Thomas J. Bata returned to Zlín to do his part to help the city reclaim its legacy. Though his return did not ultimately kick-start the shoe industry in the city, it did energize its citizens to revitalize their history.

“The shoe factory, with its brick buildings, still exists,” says Silvie Lečíková, the marketing manager for Zlín’s Museum of Southeast Moravia, which is part of the Baťa Institute. “Most of the buildings raised before World War II, including the houses for employees of the Baťa company, still exist, and some still serve their purpose.”

In addition to the notable structures that survived the war (including the aforementioned hospital, cinema, and Baťa’s Skyscraper), today Zlín’s museums and educational institutions are focused on telling the city’s own fascinating story, the influence of which remains palpable in the spirit of its people. “One simply cannot live in Zlín and not feel its history,” Lečíková says.

This post was written in partnership with CzechTourism. For more obscure and unconventional stories, from the Land of Stories, head here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook