AO Edited

The Armour-Stiner Octagon House

This fancifully decorated Victorian home in New York’s Hudson Valley is the only known fully domed octagonal residence in the United States.

Mimicking the design of Donato Bramante’s 1502 Tempietto in Rome, the dome on this brightly painted abode isn’t the only thing that sets it apart from its neighbors. Originally constructed sans dome and cupola in 1859-1860 for New York financier Paul J. Armour, the home has been occupied by a tea importer, an adventurer, a famous poet, and an architect, all of whom have left their own unique marks.

Paul J. Armour likely got the idea for the shape of his home from the book A Home for All by noted phrenologist, sexologist, and amateur architect Orson Squire Fowler. Fowler extolls the merits of octagonal structures over traditional square or rectangular dwellings in his book. He argues that octagonal-shaped homes have more space, allow for a better arrangement of rooms, have more natural light, better ventilation, and can be more efficiently heated. Though some examples of octagonal structures were built in America before Fowler’s 1848 publication— most notably Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest Estate—the text set off a short-lived octagon house boom in the mid-19th century. Fowler started building his own octagonal home in the Hudson Valley town of Fishkill in 1848, and it was completed in 1853.

In 1872, tea importer Joseph Stiner purchased the home as a country retreat. While Armour’s original design for the house adhered strictly to Fowler’s practical philosophies, Stiner turned it into an ornate Victorian folly. In 1876, Stiner added the slate-roofed, two-story dome and cupola, along with a slew of other additions. He added a wrap-around veranda supported by nearly sixty columns and fencing emblazoned with cast-iron portraits of his beloved terrier Prince, splashed the facade with more than twenty different vibrant colors, raised the height of the home to ninety-five feet, and added interior flourishes such as decorative glass panels etched with his initials. From the observatory in the cupola, Stiner would have an amazing view of the Hudson River.

After Stiner, the home welcomed various occupants. In the 1940s, adventuring journalist Aleko Lilius rented the home for a few years. Lilius was known for his 1920s book I Sailed with Chinese Pirates, in which he recounts (largely exaggerated) tales of conquest alongside female pirate chief, Lai Choi San. The home’s ornate style went out of fashion and was gradually tempered by neutral paints and changing decorative tastes. Later in the 1940s, Carl Carmer, an author, poet, and historian, became the home’s most famous resident. Carmer, known for his autobiographical book Stars Fell on Alabama and the series of books Rivers of America, lived in the home with his wife, photographer Elizabeth Black, until 1976.

When the couple could no longer keep up with the maintenance of the historic property, they sold it to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to save it from demolition. The trust, which acquired the property under the umbrella of its new Limited Endangered Building Fund, held onto it for only a couple of years before reselling it to current owner Joseph P. Lombardi in 1978. It was the first National Trust property to be bought from and then sold to a private owner.

Lombardi, an architect specializing in historic preservation and conservation, was the perfect person to take over at that time. By 1978, the historic home was in disrepair, and the dome was near collapse. After years of sagging, the dome had to be jacked up to its original height and squeezed back into shape. Working with engineer Eugene Avallone, Lombardi devised a system of high tension steel cables that girdled the dome back to its original shape and size. The stabilization process took three years. A permanent steel band was installed around the base of the dome to prevent future movement.

Once structurally sound, the home was brought back to its extravagant, 19th-century, polychromatic glory under the management of Joseph’s son Michael Hall Lombardi. Paint analysis helped determine original paint colors for the interior spaces and the exterior of the house. Rooms were extensively researched and meticulously restored to the Neo-Roman style applied by Stiner in the late 1800s. The third-floor Egyptian Revival music room, which breaks from the style of the rest of the house, is said to be the only domestic room of its kind still in existence. Stiner’s original furnishings were found at an auction and returned to the room where they now sit under a star-emblazoned ceiling and walls encircled by Egyptian scenes.

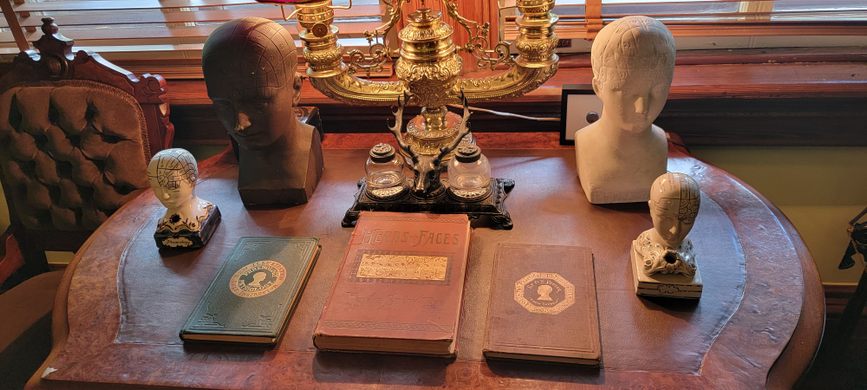

Walking around the home today, which still serves as a private residence, you can see the influences of previous and current owners and the times in which they lived. You might see a TV in one room and a phrenologist bust in the next, a collection of antique tea tins in the kitchen, and a 1930s mystery novel, The Octagon House by Phoebe Atwood Taylor, on a nightstand.

And, of course, no Victorian home is complete without a resident ghost. Joseph Lombardi told the Riverfront Enterprise that a young woman who once lived there haunts the house. The woman was in a forbidden romance with her neighbor, so they eloped and ran away to sea. Unfortunately, the sea is where they met their demise. Lombardi told the paper that the tell-tale sign of the ghost’s presence is the smell of lilacs.

Know Before You Go

The Octagon House still serves as the Lombardis' private residence, but it is open seasonally for guided tours. The dome and cupola are not open to the public. You can book a tour on the house's website.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook