Bevin Boys Memorial

A long-overdue monument to the forgotten British men drafted into the coal mines during World War II.

For far too long, Britain’s conscripted coal miners of World War II were not given the recognition they deserved. In May, 2013, this memorial was unveiled to help put that right.

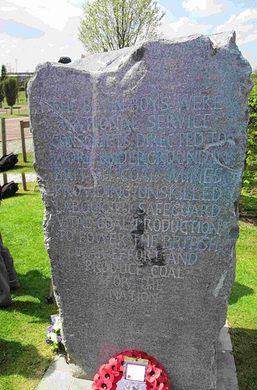

Located at the National Memorial Arboretum at Alrewas, the monument is made up of four stone pillars carved from Kilkenny stone expected to weather to a coal-black color. It remembers the conscripted miners who served their country in the coal pits during World War II, known as “Bevin Boys.”

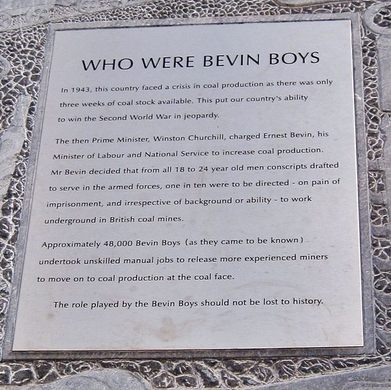

At the beginning of the war, the British government made the mistake of drafting so many young men into the armed forces it left a shortage of labor for the coal mines. By the middle of 1943 the mines had lost 36,000 workers, with more young recruits going into the army instead of replacing the men in the mines.

The dwindling supply of coal needed to power the war was reaching crisis levels, and a plea asking men to volunteer for work in the mines instead of the armed forces failed. Many feared the stigma of not being in uniform, and others preferred active military service to serving thousands of feet underground in an industry where the death rate at the time was appalling. It is estimated that 5,000 coal miners were killed in British mines during the Second World War.

The answer was compulsory conscription into the mines, a scheme proposed by Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour and National Service. In a later speech he referred to the conscripts as “boys,” leading to the nickname, “Bevin Boys.”

Some 48,000 Bevin Boys served in World War II. Between 1943 and 1945, 10 percent of male conscripts between 18 and 25 years old were sent to work in the mines. Every week one of Bevin’s secretaries pulled a number at random from a hat containing 10 digits, zero through 9, and all men with a national service registration number ending in that digit were sent to the mines.

This caused a deal of upset, as many young men wanted to join the fighting forces and felt that as miners they would not be value. Indeed this proved to be the case; many suffered taunts from the public, and even interest from the police, because they were not in uniform.

Conscripted miners came from many different backgrounds, from office workers to manual laborers, and included some whose education would have qualified them as commissioned officers. In the pits, this counted for nothing, as they all started at the same level.

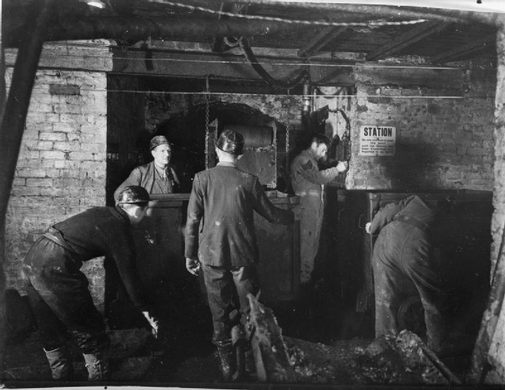

The Bevin Boys were given six weeks’ training. The work was normally typical deep coal mining, although some were sent to other mines such as gypsum. They would work thousands of feet underground, but they rarely would work on the coal face (unless they had previously been miners), largely because of resistance from experienced coal face workers who were paid according to the amount of coal they produced.

Unless they were already skilled as an electrician or fitter, they would often do haulage work, like the dangerous work of clipping and un-clipping underground rail wagons (tubs) onto and off continuously moving haulage ropes. Accidents were common and near misses an almost daily event.

It is believed that the first Bevin Boy to be killed in an accident was Henry Robert Hale, aged 18. Hailing from London, he had only been working a month after his training when he was killed in 1944. Bevin Boys disabled by a mining accident did not get a pension, and if they were killed their dependents were not provided for.

The need for coal in Britain was so great, the program did not end until 1948, two years after most servicemen had been demobilized. At that time the Bevin Boys received minimal recognition for their efforts. Unlike those in the armed forces, they did not even have the right to return to the jobs they had held previously. To make matters worse, all records of the Bevin Boys were destroyed in 1950 so a former Bevin Boy could never prove what service he had done in the war.

Bevin Boys were not really recognized as contributors to the war effort for many years after the end of the war. Until 2004, they were not even allowed to march as a group in the annual parade past the cenotaph on remembrance Sunday although other civilian services had long been represented.

In 2007, then Prime Minister Tony Blair informed Parliament that thousands of mining conscripts would finally receive a long-overdue recognition. He stated that the Bevin Boys would be rewarded with a Veterans Badge similar to the HM Armed Forces Badge awarded by the Ministry of Defence. However because the records had been destroyed, it was necessary for individuals to apply. On the 60th anniversary of the discharge of the last Bevin Boys, the first badges were awarded at a reception at Downing Street. Five years later, the Bevin Boys memorial was unveiled.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook