Cesare Lombroso's Museum of Criminal Anthropology

The astonishing collection of an infamous criminologist.

Once only open to academics, Lombroso’s Museum has opened its doors to the public.As the criminologist Cesare Lombroso examined the skull of the autopsied body of Giuseppe Villela, the notorious Italian criminal he had just dissected, he discovered a cranial anomaly known as a “median occipital fossette.” Lombroso was suddenly overtaken by flash of insight. As he would write many years later:

“The sight of that fossette suddenly appeared to me like a broad plain beneath an infinite horizon, the nature of the criminal was illuminated, he must have reproduced in our day the traits of primitive man going back as far as the carnivores.”

What Lombroso felt he had discovered would become his legacy and known throughout the world as the Italian School of Criminology. Lombroso felt that he understood the true scientific nature of crime and people who broke the law. According to Lombroso, a person didn’t learn to become a criminal—they were born to become one. Also called “biological determinism,” Lombroso’s theory of “anthropological criminology” and the upbeat sounding “positivist criminology” was that criminals were a kind of evolutionary throwback, physically devolved, and they couldn’t change because it was part of their biology.

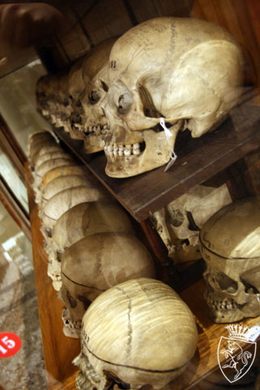

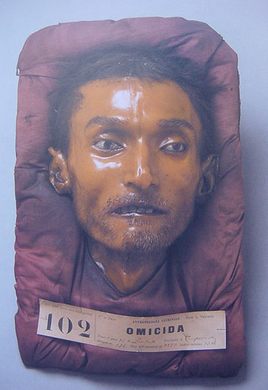

According to Lombroso’s theory, there were many physical characteristics tied to being a “natural born criminal,” including large jaws, forward projection of jaw, low sloping foreheads, high cheekbones, flattened or upturned nose, handle-shaped ears, large chins, hawk-like noses or fleshy lips, hard shifty eyes, scanty beard or baldness, insensitivity to pain and long arms.

Lombroso also falsely believed that race was an indicator of evolution with Black people being the least evolved and white people being the most evolved, or in his words “only we white people have reached the ultimate symmetry of bodily form.” Despite these beliefs (which were rather common at the time) Lombroso believed in reform rather than punishment, and was against capital punishment.

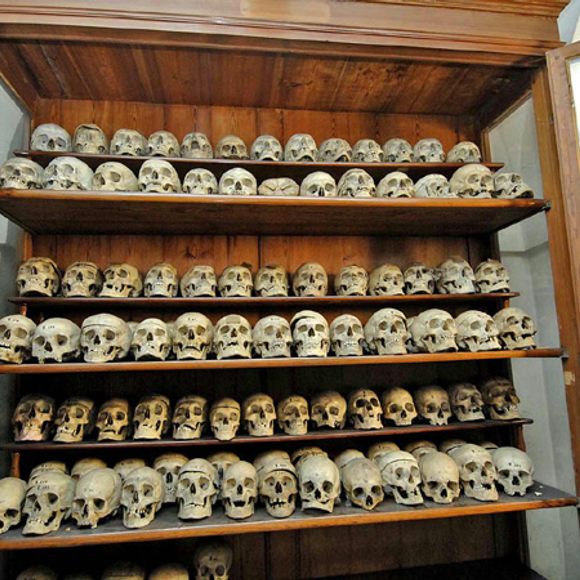

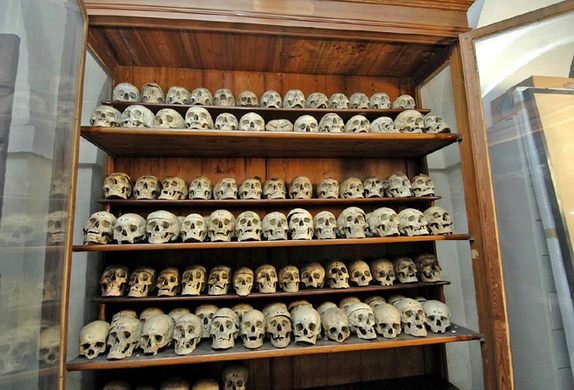

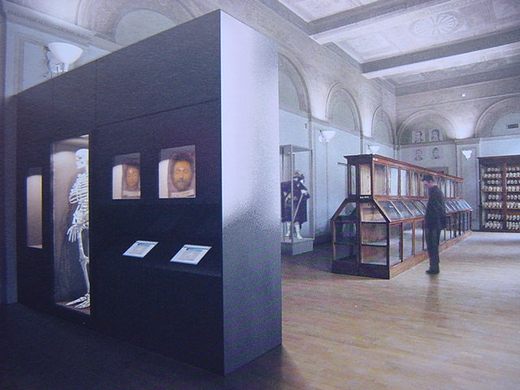

As part of his studies Lombroso collected specimens, many biological, such as numerous skulls, but also weapons and other criminological relics. In 1892 Lombroso opened a museum in Turin (narrowly escaping having his collection seized by Rome) and bragged that “our school has attracted and convinced the best scientists in Europe who did not disdain to send us, as proof of their support, the most valuable documents in their collections.”

Lambroso’s daughter described him as “a born collector–while he walked, while he talked, while he was engaged in discussion; in town, in the country, in court, in prison, on his travels, he was always studying something that no one could see, thus amassing or buying a wealth of curiosities, which at the time no one, not even he himself, could have placed a value on…”

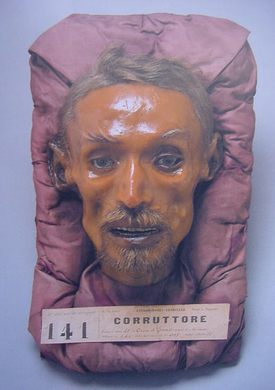

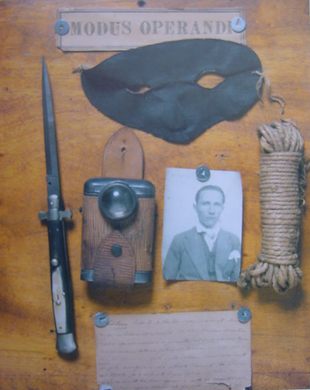

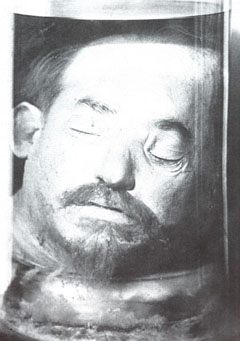

Among the collections he acquired for the museum are hundreds of skulls of soldiers and civilians, anatomical specimens from “far-off lands” as well as those of criminals and madmen, dozens of complete skeletons, brains, and wax models of “natural criminals” as well as “drawings, photos, criminal evidence, anatomical sections of ‘madmen and criminals’ and work produced by criminals in the last century, the Gallows of Turin, which were in use until the city’s final hanging in 1865 and the possessions of a man known as White Stag, a renowned impostor who convinced Europe he was a great Native American chief.”

The collection is topped off by the head of Lombroso himself, “perfectly preserved in a glass chamber.”

Know Before You Go

The museum is open Monday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. It is closed on Sundays. Check the website for ticket information and pricing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook