Danzanravjaa Museum

Hidden treasures belonging to Mongolia's most revered and multi-talented monk spent decades buried in the Gobi desert.

The story of the museum dedicated to Dulduityn Danzanravjaa, one of Mongolia’s most revered and multi-talented monks, is almost as dramatic as the man himself. His treasured possessions, such as several kangling (flute made of human femur), a damaru (double-headed drum made of two human skulls), and two kapala (cup made of human skull cups) were long buried in remote, secret locations around the Gobi desert.

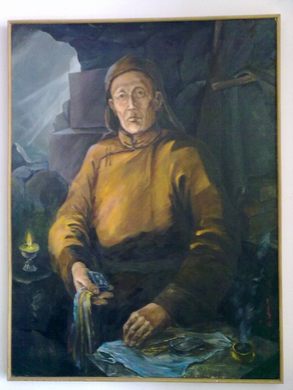

Danzanravjaa, known by epithets such as the “Lama of the Gobi,” belonged to the Nyingma school of Buddhism, and was the fifth reincarnation in the Noyon Khutukt line of monks. He was born in 1803 and was identified as a lama when he was 12, before which he wandered around the Gobi with his minstrel father, singing songs for money.

His biggest claim to fame is his poetry, in which he criticized social evils that he witnessed around him. This is followed closely by his divination, paintings, and writings on medicine, philosophy, and astrology. He was also an active advocate for public education, and set up a primary school, a library and a museum at the monastery where he resided. As if this were not enough, Dulduityn Danzanravjaa was also a talented dancer and choreographer, and established a theatre company that staged dances, plays, and operas promoting women’s rights. In short, Danzanravjaa was the consummate Renaissance man, and is remembered for his immense contributions to all of these fields.

Danzanravjaa died in 1856 under shadowy circumstances, believed to have been poisoned by one of his enemies. With the end of his life began the story of the museum in his name that stands today. One of his trusted disciples, Balchinchoijoo collected all his possessions, stored them in crates, and acted as the curator of Danzanravjaa’s relics. This role was passed down to his heirs, and it was the duty of a descendent named Tudev to safeguard them during the Soviet era in the 20th century. At the time, there was a crackdown against religious institutions and artifacts, and hundreds of monastic complexes in Mongolia were destroyed.

Tudev carefully prepared each crate for storage and even set traps for extra protection. Every night he buried one in a remote location in the Gobi desert, and memorized the location. In this manner, he managed to bury 64 of the nearly 1,500 crates before the army destroyed the remaining artifacts. He passed on the information about the location of the buried treasures only to his heir, his grandson Altangerel.

When Mongolia became free of Communist rule in 1990, it was finally safe for Altangerel to dig up the crates and see what remained of artifacts. Another 24 boxes were unearthed and the relics were placed in the museum in Sainshand, which was opened the following year.

Among the exhibits are the costumes used for his theatrical productions, the aforementioned kangling, damaru, and kapala, some shamanistic implements, samples of his manuscripts, and other paraphernalia rescued from the many monasteries that he set up.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook