Fort Robinson State Park

Site of the 1879 Cheyenne Outbreak and the site where famed Sioux chief Crazy Horse met his fate.

Fort Robinson was operated as a military camp from the 1873 until after World War II. Many of its original buildings survived and remain in use at the park today, and others have been reconstructed.

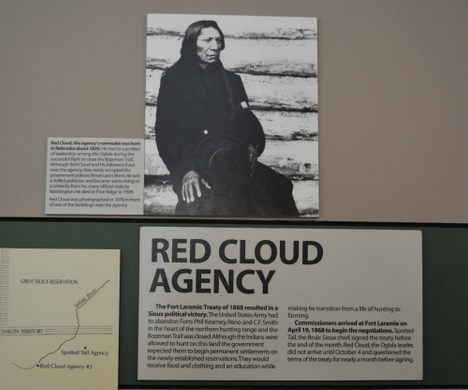

After the Civil War, the United States redeployed many federal troops west to continue national expansion by taking Indigenous land. Indigenous people resisted. The ensuing campaigns, which some call the “Indian Wars,” lasted through 1877. In 1873, the Red Cloud Agency for the Oglala Lakota and Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho was moved from its North Platte River location to the White River in the northwest corner of Nebraska Territory. In March of 1974, the U.S. Government established a military camp there to quell uprisings by the 13,000 Lakota resettled at the agency after being forced off their lands of the Northern Great Plains.

The camp was named in honor of Lt. Levi H. Robinson, who had been killed by Native Americans while on a wood detail in February of 1874. After the camp was moved to its current location, it was renamed Fort Robinson in 1878.

Following the destruction of Custer’s troops at the Little Big Horn and the eventual defeat of Crazy Horse, a member of the Oglalas, he surrendered his band at Fort Robinson. On September 5, 1877, during an attempt to arrest him, Crazy Horse was bayoneted by US Army troops and died at a small stockade on the grounds of the camp.

Fort Robinson was also the site of a massacre of Cheyennes in January 1879. In the summer of 1878, a band of Cheyennes lead by Chief Morning Star (also known as Dull Knife) left their reservation in Oklahoma Territory to return home to the North Platte River valley. The band lead the US Army on a chase across the plains of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota for most of five months. The band was eventually captured and taken to Fort Robinson.

The group was treated inhumanely, held in an unheated barracks without food or water. Fearing that they would be returned to the Indian Territory or killed like Crazy Horse, the band, which included many women and children, broke out of the barracks. They were chased and killed by the fort’s soldiers in a running battle across the current site of the state park’s campground. Approximately 50 of the 150 Native American prisoners were killed in what the U.S. Supreme Court labeled “one of the most melancholy of Indian tragedies.” Mari Sandoz wrote Cheyenne Autumn detailing the account, and John Ford’s last western film was an adaptation of the book.

In 1885, the Ninth Cavalry Regiment was assign to Fort Robinson. This was an all Black unit. Charles Young, one of the first Black officers to graduate from West Point, was assigned to the fort from 1889 to 1890. The fort continued to serve as the regimental headquarters for the Ninth Cavalry until 1904.

At the end of World War I, Fort Robinson was repurposed as a remount depot for the breeding and training of horses and mules for military service. It became the largest facility of its kind. Horse stock owned by the military was used to breed local stock to improve it for acquisition to the military’s needs.

The fort was abandoned by the U.S. Army in 1947 and was used by the USDA as a livestock research station until the early 1970s. Nebraska obtained title to the historic buildings and established a park there in 1956. The remainder of the fort was deeded to Nebraska when the USDA ceased operations.

Today, Fort Robinson State Park offers a wide range of activities. Officer quarters are available for rent, a museum of materials found in one of the old warehouses is a fascinating look into the materials of a military fort and a pair of mammoths have been found on the grounds that are eternally locked in mortal combat when their tusks intertwined. The fort has a rich and varied history.

Know Before You Go

Take a beautiful drive to the "high prairie" of NW Nebraska's Pine Ridge to see stunning white buttes, flower gilded prairies and this remarkable historical landmark

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook