AO Edited

Fortaleza del Real Felipe

Haunted by its violent past, this colonial bastion was the largest Spanish military installation in the Americas.

Skeletal women with wind-whipped hair, half-seen atop the ramparts in the wee hours. Children, giggling demonically as they flit down passageways. The Fortaleza del Real Felipe, in Lima’s seedy port district of El Callao, has never lacked for resident haunts.

The colonial garrison has certainly had time to accumulate them. Commissioned in 1747 by Viceroy José Antonio Manso de Velasco, the fort was the Spanish crown’s response to one of the chief irritants to its overseas empire: pirates. Starting in the 1500s, El Callao, on the Pacific coast of Peru, found itself menaced by privateers from England, France, and the Low Countries. They had set their sights on the massive silver shipments flowing through the port from mines like Cerro Rico, in present-day Bolivia. In 1624, a fleet of 11 Dutch yachts under buccaneer Jacques l’Hermite blockaded Callao’s harbor for three months, setting fire to galleons in the bay and sending limeños scurrying for the hills.

Manso de Velasco’s new citadel aimed to halt these depredations. With its bomb-proof walls and pentagonal, Vauban-style design, the fortress sprawled over 70,000 square meters—the largest Spanish military installation on American soil. State-of-the-art features included a 16-meter-wide moat, earthworks to meld the fort with the landscape, bastions at each of the five corners, wells for drinking water, barracks, a hospital, and 188 bronze and 124 iron cannons jutting out atop the ramparts. All this engineering served its purpose: in almost 100 years of active use, the fort was never taken.

Peru’s wars of independence gave the Real Felipe a starring role—albeit on the royalist side. In 1816, it served as a bastion for Spanish grenadiers, who used its artillery to beat back an assault by Admiral William Brown, an Irish-born republican whose flotilla had launched a bombardment from El Callao’s harbor. In 1819, it again proved too strong for patriot forces—this time under Lord Thomas Cochrane, who like Brown found his naval siege of Lima thwarted by the Real Felipe’s superior barricades and firepower. Ultimately the fort’s impregnability compelled José de San Martín, the Argentine liberator, to forego a marine invasion and assail Lima by land, marching north from Pisco, on Peru’s southern coast. When he finally reached Callao in 1821, royalists under Field Marshal José de La Mar defended the fort ferociously but were forced to capitulate in the face of a ration shortage and surging cholera outbreak.

Today, the Real Felipe’s legacy of violence can still be sensed in its somber battlements. Its ugly, wartlike walls remain the embodiment of blind, brute force.

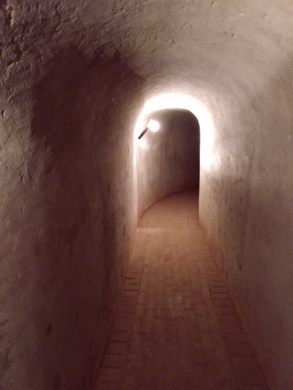

The brutality is most evident in the Torreones del Rey y de la Reina (Towers of the King and Queen). These twin fortresses within a fortress became chambers of horrors for their patriot prisoners, who were sadistically crammed into the towers’ dungeons and forced to remain standing round the clock—even while asleep. Overflow inmates were shackled in a maze of asphyxiating corridors, where at any moment they were prone to be doused with boiling water. Life expectancy for captives: 60 days.

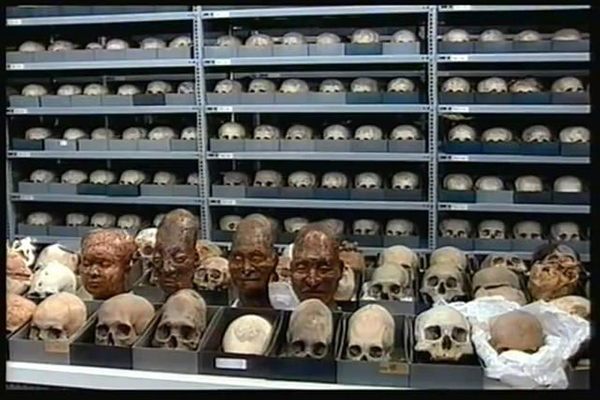

With such an accumulation of bad history, it’s unsurprising that Real Felipe scores high on the paranormal-activity scale. Manifestations run the gamut: suicidal soldiers hurling themselves from parapets, imps in sailor garb darting amidst the dungeons. The oftenest-told legend is that of the “white lady,” who appears croaking a funereal melody on the Torreón del Rey’s drawbridge after midnight. Rumored to be of a highborn Spanish family, she fled an 1824 uprising in El Callao by holing up in the fortress, where she contracted the plague and died.

The Real Felipe’s walls are little visited today. Something in their long, empty vistas and queer shadows provokes disquiet. For a few, however, the tight, airless cells and looming towers afford a window onto the violence that was colonial Peru, still vexed two centuries later by its unquiet dead.

Know Before You Go

The fortress is situated six miles west of downtown Lima, near Callao’s Mercado Central. The neighborhood can be dicey, so the best way to go is to take a taxi.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook