Geronimo Surrender Monument

A stone pillar commemorates the surrender of the extraordinary Apache leader.

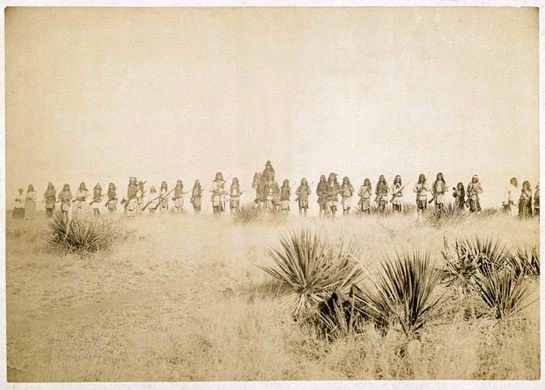

On September 4, 1886, the Apache leader Geronimo and his band of followers surrendered to General Nelson Miles in Skeleton Canyon, Arizona. After years on the run and guerrilla warfare with both United States and Mexican soldiers, the formidable medicine man and war leader submitted to U.S. custody for the final time.

Geronimo was born in June of 1829 near present-day Turkey Creek, New Mexico (at the time it was Mexico) into the Bedonkohe band of the Apache tribe. When Geronimo was 28 years old his camp was attacked by Mexican soldiers. He and most of the Apache men were away at the time and returned to see many of the women and children had been slaughtered, including Geronimo’s mother, wife, and his three children. This massacre set him on a path of resistance against the colonizing forces that sought to control and oppress the Apache.

For several decades thereafter, Geronimo helped lead raids against incursions of settlers into traditional Apache lands. His guerrilla raids became notorious for their ferocity and efficiency, often successfully taking on units of soldiers much larger than his own. He frustrated pursuing armies by escaping seemingly hopeless situations and crossing back and forth across international borders to thwart his enemies. His exploits became the stuff of legend. According to one possibly apocryphal tale, American troops cornered Geronimo and his warriors, who then fled into a cave. The soldiers waited outside, ready to arrest or kill him and his men. But while the soldiers were waiting, they received reports that Geronimo and his band were spotted elsewhere. They searched the cave and found it empty. Bafflingly, it did not appear have another exit.

Geronimo led three rebellions against the United States, recruiting Apaches who refused to continue living in restrictive reservations and wished to return to living in their former nomadic ways. The last of these rebellions began in 1885, when Geronimo and his recruits escaped from the San Carlos Reservation and into Mexico. On the run and running out of supplies, Geronimo was persuaded to surrender. He and his band camped out in Mexico and prepared to cross the border to surrender the next day. An American soldier who sold them whiskey warned them that the plan was to wipe them out as soon as they crossed into the United States. Once again, Geronimo and his men fled and evaded capture.

A few months later, Geronimo and his group were again tracked down and a U.S. soldier he respected was sent to talk with him. Captain Henry Lawton spoke the Apache language and respected their culture and customs. Geronimo allegedly saw Lawton as a formidable and honorable opponent whose word was trusted more than most soldiers. Lawton was able to convince Geronimo to surrender again, and that he and his band would not be attacked if he agreed to do so. Lawton then escorted Geronimo and his followers to Skeleton Canyon where General Miles was camped.

Geronimo spent the rest of his life as a prisoner of war. The territory of Arizona wished to have him tried and executed for his many decades of guerrilla warfare, so in order to prevent that the U.S. Army had him and his family transferred to military bases in Florida. There, a group of businessmen convinced military authorities to allow them to display Geronimo in his prison cell as a tourist attraction.

In 1894, Geronimo was transferred to Fort Sill in Oklahoma where he was given a small plot of land within the base to build a house and farm. But he was still incarcerated and forbidden from leaving without an armed military escort. He was put on display again for tourists at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901 and the World’s Fair in St. Louis in 1904.

In 1905, the famous Apache leader rode a horse in President Theodore Roosevelt’s inaugural parade. After the parade, Geronimo met with Roosevelt and begged him to allow the Apache people to be freed from their prisoner of war status. Roosevelt refused, telling Geronimo that he had a “bad heart,” and that he and his followers “were not good Indians.” Geronimo died on February 17, 1909, still a prisoner at Fort Sill. On his deathbed, he voiced his regret at having surrendered wishing instead to have fought to the bitter end.

The stone pillar commemorating Geronimo’s surrender was constructed in 1934 by the Civil Works Administration, one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. The pillar is eight miles away from the actual site of Geronimo’s surrender in Skeleton Canyon, which is on private land. The plaque on the pillar uses some questionable language to describe the events it commemorates, calling Geronimo and his band “hostiles,” citing the bravery of the U.S. troops without adding context or the Apache perspective, and falsely claiming that the surrender marked the end of U.S. military warfare against native peoples. Regardless of this, the pillar does undoubtedly mark an important event in history and the life of an extraordinary person.

Know Before You Go

The monument is along Highway 80 in remote, southeastern Arizona, only a few miles from the border with New Mexico. There is a small parking area at the site.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook