Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site

A well-preserved example of an early industrial operation in the northeastern United States.

The northeastern United States does not leap to mind when iron mining is mentioned. However, small-scale iron mining in this area was common from colonial times up into the 19th century. Many of the operations could be even considered a cottage industry, with iron being extracted for local use by an individual blacksmith.

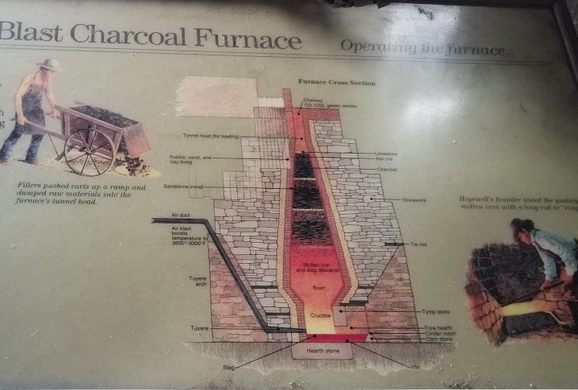

Hopewell Furnace, by contrast, was a large operation, a so-called “iron plantation” almost at a proto-industrial scale. It was active from 1771 through 1883 and furnished iron for both the Revolutionary War and the American Civil War. Its heart consisted of a furnace around 32 feet high and 22 feet square that had a cross-section something like an arrowhead pointing up.

The furnace was charged with iron ore, charcoal, and limestone from the upper “point” end. Air was blown in near the base of the furnace, at first by large bellows and later by a piston system driven by a water wheel. With this airflow, the temperatures in the wide middle of the furnace reached around 3,000°F, at which point the reactions to produce molten iron could proceed. The limestone also reacted with any impurities in the ore to produce molten slag, basically glass.

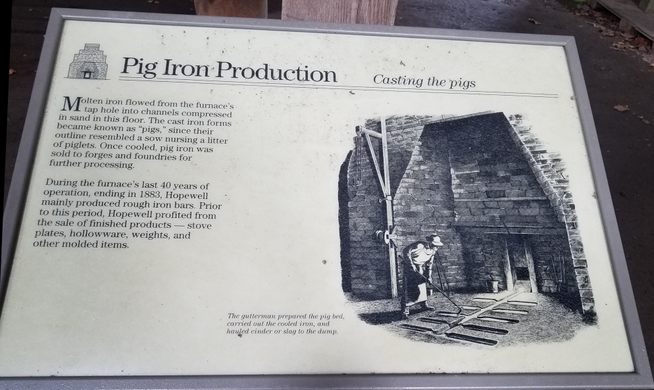

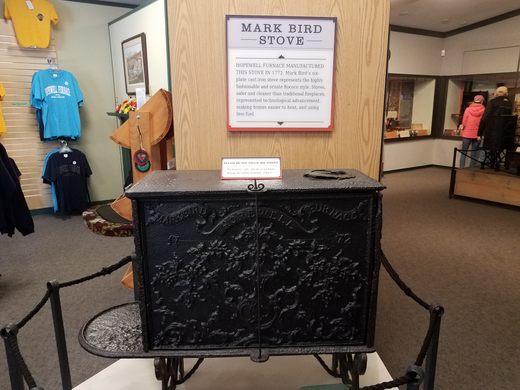

The liquids would fall and collect at the bottom of the furnace. Molten slag and molten iron act like oil and water, with the slag floating on top of the iron, so they can be drawn off separately. The slag was discarded, while the iron was drained out into molds. In the early years cast iron objects were made, iron stoves in particular. By the time the operation shut down, however, raw ingots of so-called “pig iron” were the only product, as casting iron objects was no longer competitive.

The furnace was run 24 hours a day except for a maintenance shut-down about once a year. Iron was typically drawn off twice a day, about a ton at a time—a substantial output in those days. The iron ore was high quality, obtained from metamorphic rocks in the area.

Indeed, some of these deposits were worked until the 1970s. Limestone was also abundant locally. The charcoal was made from the local hardwood forests by means of charcoal kilns at the site. In the 1840s, the operation tried making coke from anthracite as an alternative, but that experiment foundered due to poor design and high transportation costs.

Hopewell Furnace finally shut down completely in 1883, as it could not compete with the large-scale consolidation of iron mining and smelting made possible by rail transportation of both raw materials and finished products. Charcoal had also become an obsolete technology, with newer operations using coke made from coal.

Know Before You Go

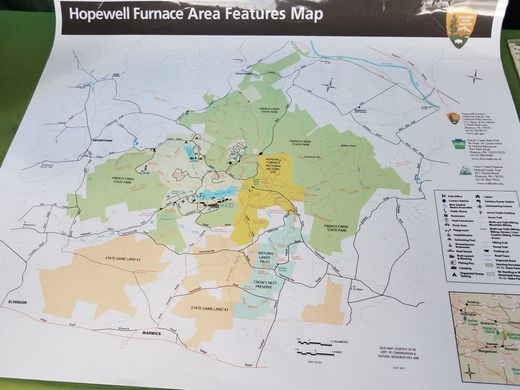

Hopewell Furnace is a National Park Service Historic Site, complete with a visitor center where you enter the site itself. Check the website for current entry fees. The main entrance, which is well-marked, is to the west off Pennsylvania State Route 345 where it intersects Hopewell Road.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook