AO Edited

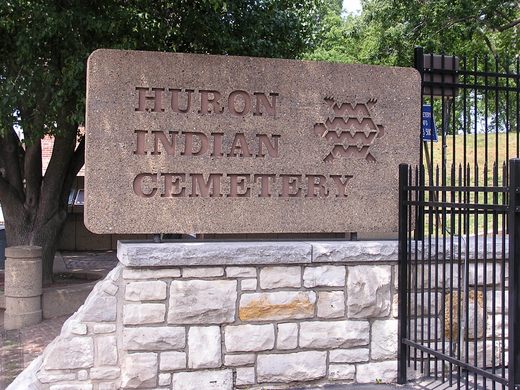

Huron Indian Cemetery

This sacred space and gathering spot for the Wyandot Nation has been the surrounded by controversy and confusion.

This small corner of land tucked away between libraries and government offices has a somber history that has been controversial and sacred in turns.

The Huron Indian Cemetery, also known as the Wyandot National Burying Ground, was founded in 1843 after the forced displacement of the Wyandotte Nation, a move that took them from Ohio to Kansas. The cemetery became the final resting place for an unknown number of Native Americans, though there is limited documentation of who is buried here.

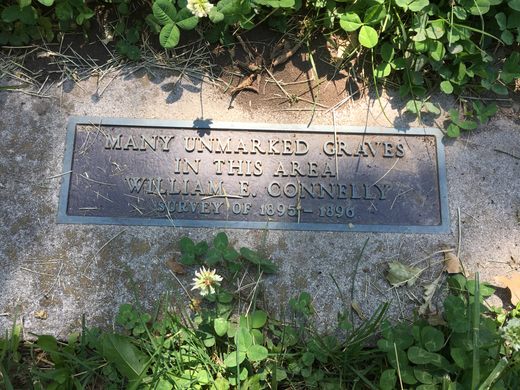

After the move, roughly 100 Native individuals succumbed to illness (presumably typhoid or measles). Their bodies were carried to a ridge overlooking the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, thus establishing the cemetery. The land was eventually ceded by the government to the Wyandotte Nation, giving them rights to the cemetery until 1855, when the nation’s tribal status was dissolved. Regardless of this, the cemetery was still designated a burial ground and continued its purpose.

In the 1890s, the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma agreed to sell the land to local developers and in 1906, the land was set to be sold and the remains moved to another cemetery nearby. However, this move was a controversial one. A set of sisters, daughters of Andrew Syrenus Conley, fought this sale to the point of essentially barricading their family’s burial site and defending it at gunpoint for nearly two years.

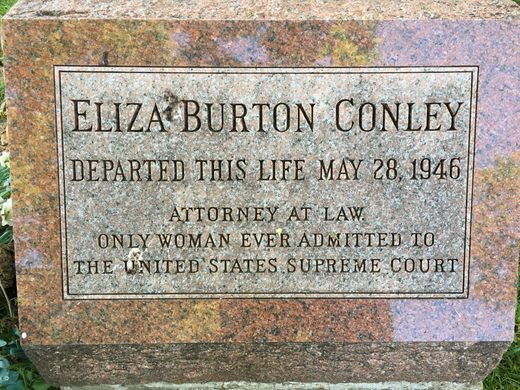

One of the sisters, Eliza “Lyda” Conley, became the first Native woman attorney admitted into the Supreme Court when she argued the cemetery’s case and attempted to prevent the sale of the land. Despite her plea and the court being sympathetic, the court did not rule in her favor.

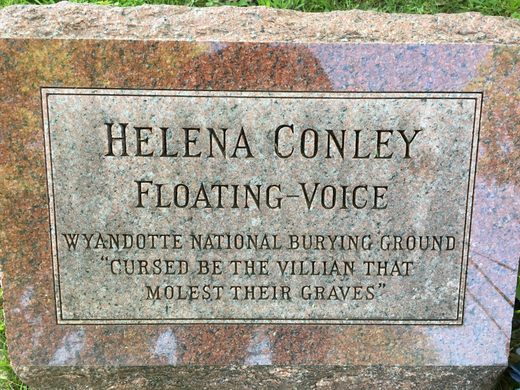

Despite this apparent failure, in 1916, Congress did pass legislation to protect the cemetery. This was done with the aid of Kansas Senator Charles Curtis, a multiracial politician who would eventually become vice president to Herbert Hoover. Lyda Conley participated in the care of the cemetery, and she and her sisters were eventually buried beside her parents. Her sister Helena’s grave even forebodingly reads ‘Cursed be the villain that molest their graves’ as what seems to be a final warning.

Numerous other attempts have been made to sell the land, but the controversy and battles were almost effectively resolved in September of 1971, when the cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The final resolution came in 1998, when the Wyandotte Nations of Oklahoma and Kansas both formally signed an agreement that the land would be used exclusively for religious and cultural purposes, and officially deemed it a sacred site.

Know Before You Go

The cemetery is located on the corner of 7th and Ann St. The entrance is on 7th Street.

Unfortunately, the cemetery entrances have fallen into disrepair. The steps up to the site at the main and back entrance have completely rotted away. The site is still very easy to get to and despite the stairs that are missing you can just walk up in the grass.

On the Southside of the cemetery are groups of mass graves and gravesites who are unknown.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook