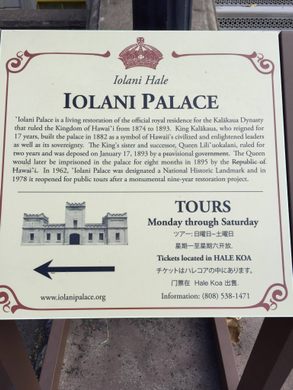

Iolani Palace

The only royal palace on U.S. soil has been a territorial capitol, a military headquarters, and a prison for a queen.

In 1882, the Kingdom of Hawai’i unveiled a new royal residence that was intended to cement the nation’s sovereignty and status as a modern state. A mere 11 years later, it witnessed some of the most dramatic events in the island monarchy’s demise.

The site of Iolani Palace had been the seat of royal power in Hawai’i since King Kamehameha III moved the capital from Lahaina to Honolulu in 1845. At the time, however, the structure on the premises was called Hale Alii (“House of the Chief”) and was a traditional Hawaiian great house, rather than the European-inspired palace that stands there now. That building was commissioned almost 30 years later, with the ascension to the throne of King David Kalakaua.

King Kalakaua was the first Hawaiian king to visit the United States, as well as the first Hawaiian king to travel around the world. Hawai’i’s “Merrie Monarch” known for socializing and entertaining, he was also a vocal advocate for Hawaiian arts and culture, including reviving hula after it had been banned in 1830. When his rule began in 1874, he found the old great house (which had been renamed Iolani, meaning “royal hawk,” by King Kamehameha V in honor of his brother) to be in poor shape and decided that the Kingdom ought to have a palace that would announce its presence in the modern political landscape.

The old house was demolished, and the cornerstone for the new Iolani Palace was laid on December 31, 1879. Completed in 1882, the palace is considered the finest example of the Hawaiian Renaissance style of architecture, characterized by a melding of historic Italian forms with Hawaiian elements that produced sleek, well-ornamented facades with delicate columns and wide verandas. In fact, its design is so singular that it earned its own unique appellation: it is the only American Florentine building anywhere in the world.

After King Kalakaua died while seeking treatment for kidney disease in San Francisco in 1891, he was succeeded by his sister Queen Liliuokalani. However, her plans to strengthen the Hawaiian monarchy and restrict suffrage to Hawaiian subjects quickly inspired rancorous and potent opposition from Hawaiian-born Americans, naturalized citizens, and foreign nationals. With aid from the American Minister to Hawai’i, the “Committee for Safety” overthrew the government of Liliuokalani and she was forced to yield authority in 1893. A subsequent attempt to restore the monarchy led to Liliuokalani’s arrest, full abdication, and humiliating public trial, in the throne room of Iolani Palace. She was subsequently kept under house arrest in a room on the second floor of the palace for nine months.

After the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai’i, Iolani Palace served as the seat of power of the ensuing Provisional Government, Territorial Government, Military Governor (while Hawai’i was under martial law during World War II), and finally State Government when Hawai’i was admitted to the Union in 1959. However, Hawai’i’s first governor, John Burns, quickly moved state offices to a different location and undertook a project to restore Iolani to its former splendor. It officially ceased to be the state capitol in 1969, and reopened as a museum in 1978.

The museum sought to recreate the environment that existed when Iolani was still an official royal residence, including meticulous recreation of original fabrics and scouring the globe to repurchase original furnishings that were sold at public auction by the provisional government after their successful coup. Visitors can see the original Throne Room, Grand Hall, and State Dining Room, as well as the King’s and Queen’s Suites and the Imprisonment Room, which still features the Queen’s Quilt which Liliuokalani made during her incarceration.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook