AO Edited

John Muir's Alarm Clock Desk

Before he was America’s most famous preservationist, John Muir was an ingenious mechanical inventor.

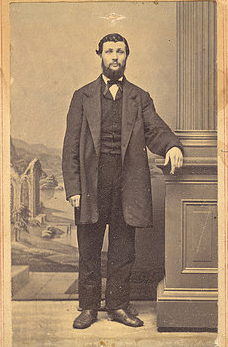

When he was a college student at the University of Wisconsin in the early 1860s, John Muir, the grandfather of American environmentalism, apparently had some trouble getting out of bed. Gifted with mechanical aptitude, however, Muir figured out a creative, and entirely caffeine-free way to get going in the morning.

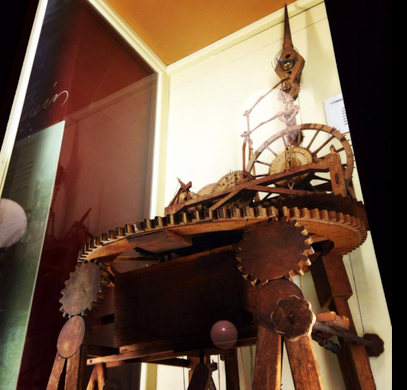

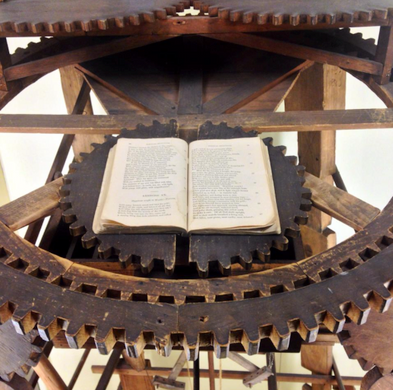

This amazing invention was a hybrid alarm clock and study desk, that quite literally chucked Muir out of bed each morning. The contraption consisted of a clockwork desk attached directly to a collapsing bed. Built out of wood, it gently but firmly slid the sleeping Muir to the floor, while also lighting a lamp.

Once launched, the clock then graciously allotted Muir a few minutes to get dressed before it quickly began ejecting and retracting his books based on a pre-set time schedule the inventor had assigned to each topic: Latin, Greek, mathematics, botany, chemistry and geology. As Muir wrote in his 1913 autobiography, after the time allotted for a subject was over, “the machinery closed the book and allowed it to drop back into its stall, then moved the rack forward and threw up the next in order.”

As a teenager growing up at Fountain Lake Farm (today a National Historic Landmark and nature preserve in Marquette County, Wisconsin), Muir – who had emigrated from Scotland with his parents as a teenager – acquired technical and farming skills and the ability to work with wood. He managed to construct an impressive set of barometers, thermometers, clocks and other ingenious, labor-saving devices, including an automatic horse-feeder. He raised university tuition money by entering some of his curious inventions, such as a clock in the shape of Father Time’s scythe, into a competition at the Wisconsin State Fair. While at school, his dormitory became a campus attraction, as he turned his room into a gallery of clever machines.

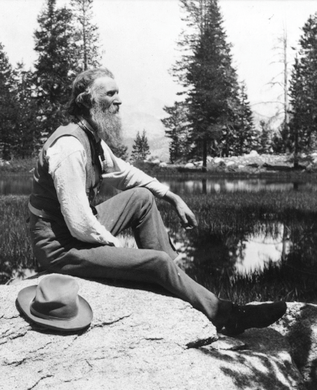

Muir’s time in Wisconsin ended, however, in 1864 when he went to work at a Canadian sawmill and rake factory. He returned to the United States in 1866. Though he had an interest in exploring nature from a young age, Muir opted for a practical profession as the foreman of a carriage factory in Indianapolis in 1867. But an accident at the factory punctured his cornea, sending his left eye into “sympathetic blindness.” And while, fortunately, much of his vision returned soon after, Muir abandoned the industrial lifestyle, bidding “adieu to mechanical inventions” and determining “to devote the rest of [his] life to the study of the inventions of God.” Behind much of his motivation to go to California lay his fearful encounter with near blindness.

In a twisted way, then, Muir’s aptitude for mechanics led to his sowing the seeds of the American preservation movement, and, in turn, the survival of places like the Yosemite Valley as national parks. Not long after Muir arrived in the Sierra Nevada, he began campaigning to save such places from developers and helping to keep much of the West’s sacred beauty from disappearing forever.

Muir’s alarm clock has been part of the collection of the Wisconsin Historical Society on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus for decades. It is often on display in a glass case on the first floor, where an excellent exhibit tells the story of the environmentalist’s early days in the Badger State.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook