Murals of Maxo Vanka

Long hidden under grime, the politically radical murals of a little known Yugoslavian master are finally getting their due.

Tucked away in the gritty working-class Pittsburgh suburb of Millvale and hidden behind the walls of an unprepossessing but historic Croatian Catholic Church are some of the most extraordinary and overlooked murals of the 1930s and ’40s.

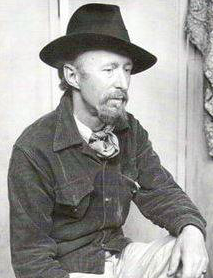

Created in protest against industrial capitalism, World War I, and the rise of Fascism, the paintings are the work of a Croatian expatriate artist, Maximilijan “Maxo” Vanka, referred to by David Byrne of the Talking Heads as “The Diego Rivera of Pittsburgh.” If you prefer legend to history, that’s here too - St. Nicholas Catholic Church is also the site of one of Pittsburgh’s lesser-known ghost stories.

Maxo Vanka (1889-1963) is most likely the illegitimate child of Hapsburg nobility. Born in the days when Croatia was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the infant Vanka was given to a peasant woman named Dora and raised in a small village outside of Zagreb. At the age of eight, his maternal grandfather learned of his existence and brought him to a castle to be educated. Vanka went on to study art in Zagreb and Brussels, graduating with top honors in 1914, the year World War I broke out. The 25-year-old artist–already a confirmed pacifist–joined the Belgian Red Cross as a medic and saw some of the worst horrors of the war on the Western Front.

In the 1920s, Maxo Vanka became one of his country’s leading painters, but in 1934, with Fascism on the rise in Europe, he immigrated to the United States.

St. Nicholas Catholic Church in Millvale, Pennsylvania was part of the first ethnic Croatian parish in the U.S. St. Nicholas’s priest in 1937, Father Albert Zagar, commissioned Vanka–an immigrant like most of his own flock–to paint a set of murals in the church. Vanka was an unorthodox choice for the job of creating what has been called “Pittsburgh’s Sistine Chapel.” Though he described himself as spiritual, Vanka wasn’t a practicing Catholic, he was friendly to Socialist politics, and married to a Jewish American (Margaret Stetten, daughter of a New York surgeon).

Over the course of eight weeks between April and June 1937, the artist completed the first round of murals–twelve paintings all told. The rest were finished in the summer and fall of 1941, just months before the U.S. entered World War II.

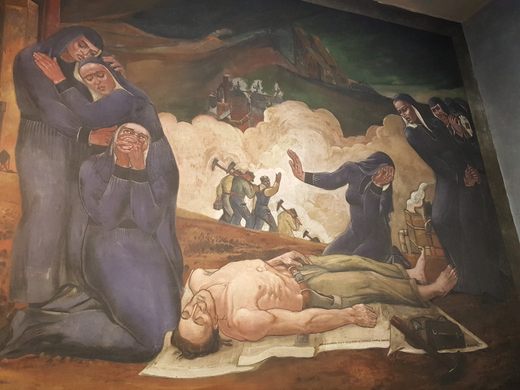

Though Vanka’s Millvale murals depict a plethora of traditional Christian religious themes, he brilliantly wove his own anxieties into the old Christian story, graphically illustrating the evils of Capitalism, the horrors of war, and Croatia’s “crucifixion” by the Ustaše - a Fascist organization that was also fiercely Catholic and anti-Semitic. The murals are an incredible translation of Christian motifs into 1940s politics. In The Battlefield Scenes, Jesus and the Virgin Mary are bayoneted by Christian soldiers; in another, the angel Injustice wears the garb of a nun and a gas mask, and holds a bleeding sword and a set of scales in which money outweighs bread; in Mati 1941, a female depiction of the artist’s beloved Croatian homeland hangs with her arms chained to a cross, shedding tears of blood.

Several of Vanka’s murals delve into the travails of American labor. In Immigrant Mother Gives Her Sons for Industry, the dark mills and mines of western Pennsylvania–once the king of American steel production–burn ominously in the distance while a dead worker lies on a Croatian newspaper surrounded by weeping mothers. In The Capitalist, an American industrialist in a top hat eats a sumptuous breakfast brought in by a black servant. As this king of industry (a jab at Pittsburgh’s rich) pores over a stock report, an angel shuns him and a skeletal hand containing fire reaches out toward him. The year is 1941.

Several of Vanka’s paintings could be set either in Europe or America. In The Simple Family Meal, a working-class family dressed in traditional Croatian clothing shares a meal. Their heads are bowed in prayer while Christ, unseen except by the little girl (who Vanka modeled after his daughter Peggy), visits and blesses them.

Around the altar and under a large painting of the Virgin Mother and Child (Mary, Queen of Croatia), Vanka’s countrymen in folk dress gather for their morning prayer (Pastoral Croatia). Vanka stated, “These murals are my contribution to America – not only mine, but my immigrant people’s, who also are grateful, like me, that they are not in the slaughter of Europe.”

Then there’s the ghost. One night in 1937, a contemporary legend goes, Vanka was up late, hurrying to finish the first round of murals. That’s when he saw “The Millvale Apparition” - the title of an article published in Harpers Magazine in April 1938 and written by Vanka’s good friend Louis Adamic. Folklore has it that this was the ghost of a former pastor who neglected his priestly duties and was paying penance for failing to serve the parish well. Although Father Zagar was present, only Vanka saw the “black-robed figure making gestures at the altar.”

Maxo Vanka went on to teach art at Delaware Valley College in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia, but never acquired widespread fame in the U.S. His Millvale Murals remain his greatest work. In 1963, while swimming off the coast of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, he is thought to have suffered a heart attack and drowned in the Pacific. His widow and daughter donated many of Vanka’s works to the Croatian Academy of Science and Arts and the Michener Museum in Doylestown, PA. In 2019, the Vanka Family gifted SPMMMV with the Vanka Collection; more than 130 drawings of Pittsburgh in 1935 and 1937 as well as preparatory sketches for the Murals.

Tragically, Vanka’s murals were nearly lost to air pollution and salt damage caused by water. In just a few short decades, Pittsburgh’s notoriously dirty air and the lack of air conditioning inside the church took a severe toll. The fine details of the murals were also obscured by the lack of lighting in the church. Professional lighting and restoration is ongoing today–with some dark squares left in a few places to show the extent of the filth that once covered these murals.

Formed in 1991 as a nonprofit separate from the church, The Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanka’s (SPMMMV) mission is to clean and restore the murals, install new lighting to improve visibility and enhance the visitor experience, and improve public information and access. As of 2022, SPMMMV has restored 14 of 25 murals and the organization received a nearly $500,000 Save America’s Treasures grant to complete Phase II of conservation. The restoration is spectacular and these historic paintings–an amazing testimony to the coming together of faith, art, and social justice–are one of the city’s best off-the-beaten-path attractions.

Know Before You Go

Millvale is a historic suburb of Pittsburgh just across the 40th Street Bridge from Lawrenceville on the Allegheny River. St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church sits at the top of a steep hill.

Driving here can be tricky, but a small parking lot is available across the street from the church. Public docent-led tours are offered by SPMMMV on Saturdays at 11a.m. and 12:30 p.m. and Mondays at 6:30PM. Private and group tours as well as school fieldtrips and education programs are available by request, for more information visit: http://vankamurals.org/visit/. Tour admission is $15 a person. Senior discount available. Children under 5 are free. Assistive Listening devices available. Non-flash photography is permitted during tours.

If you are interested in attending a public tour or scheduling a private tour when tours resume, please feel free to register for a personal notification: [email protected].

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook