The Tabulating Machine Co.

The early data processor factory founded in Washington for the 1890 U.S. Census went on to become IBM.

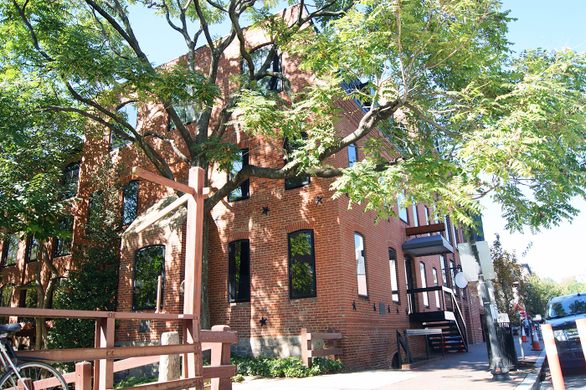

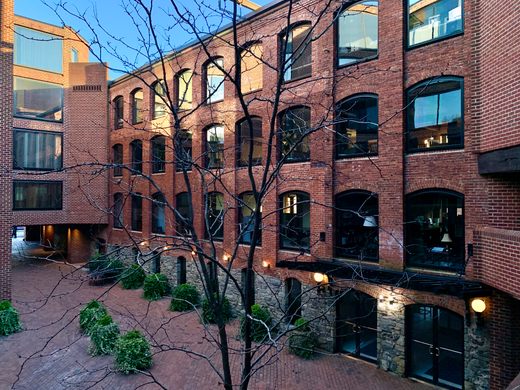

Today the U.S. technology sector is inextricably linked with the West Coast, but the history of data processing actually traces back to an unassuming brick factory in Washington, D.C. This was the Georgetown headquarters of the Tabulating Machine Company, an early analog computer manufacturer that you may know by the contemporary moniker IBM.

It makes sense that you would find the roots of computing in Washington, because it was here that bureaucrats faced one of the largest big-data challenges of the era: counting and analyzing the decennial census of a skyrocketing Industrial Revolution populace.

National head counts were a manageable expectation in the early decades of U.S. history when the population numbered just a few million. But by the late 19th century an extended explosion in immigration had swelled the count t0 60 million, and the increasingly impractical census often stretched on for years.

The holdup wasn’t so much the gathering of information as much as the analysis. Responses to dozens of questions had to be compared across the tens of millions of census cards before a final report could be issued, and processing all that data was a tedious and mind-numbing task.

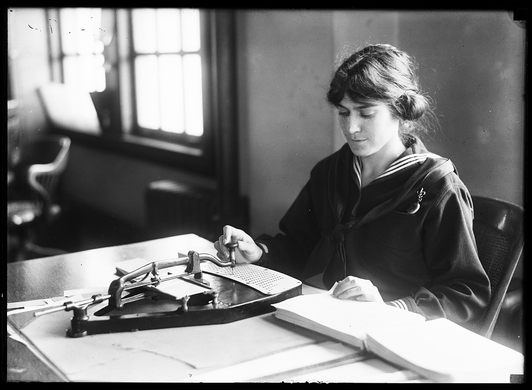

In 1890, the Census Bureau attempted its first “count by electricity,” using Washington inventor Herman Hollerith’s newly patented punch card data processor. Hollerith’s Electronic Tabulator could read manilla census cards with an array of pins that formed different electric circuits in relation to the location of hole punches.

The device could track dozens of pieces of information like gender, race, marital status, age, nationality, occupation, property value, immigration status, etc. The so-called “mechanical clerk” was also savvy enough to automatically flag unexpected data and set aside those cards for human verification. (Examples of unexpected data provided by the 1901 Evening Star include a male hat maker, a female blacksmith, or a 6-year-old girl with 10 children.)

The Hollerith Tabulator helped the government count more Americans with fewer census employees, and shave the processing time down from eight years to six. There was also the interesting coincidence that this new frontier in data processing led to the discovery by the Superintendent of the Census Bureau that “Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.” The new computing frontier coincided with and eclipsed the closure of the literal frontier.

Following on the success of the 1890 census, Hollerith aggressively exploited his tabulating patent and went after lucrative contracts with the federal government, Russia, Italy, Canada, Austria, and other nations. But he charged the U.S. so much money for the 1900 headcount that it spurred a frenzied (and ultimately successful) effort within the Census Bureau to develop an alternative data processing technology that didn’t come with Hollerith royalty payments.

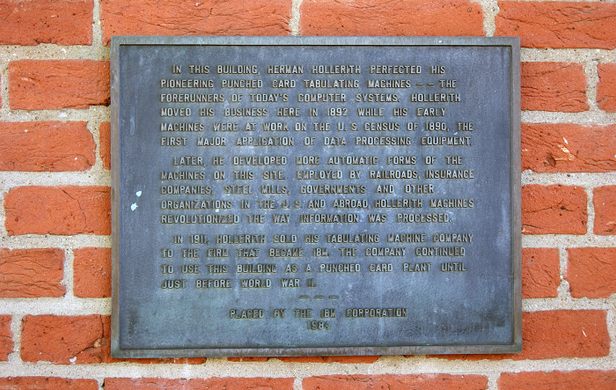

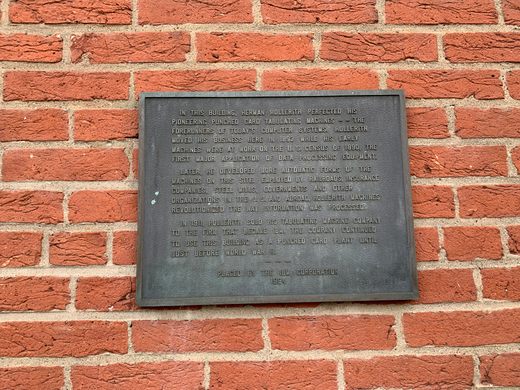

The Tabulating Machine Company continued punching away until it consolidated with the New York-based Computing Tabulating Recording Company in 1911 and was renamed IBM in the mid-1920s. The company continued producing punch card machines until 1984, when the plant finally closed. IBM placed a historical plaque on the corner of the building by 31st Street and the Canal. Hollerith is also buried nearby in the Oak Hill Cemetery.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook